We spend a lot of rehearsal time focusing on the attack of a note because that is the first thing a listener hears. A new vocabulary has even evolved. Words like chipping, bulbing, and cracking are well-known to most students. However, note endings are equally important because they are the last thing a listener hears.

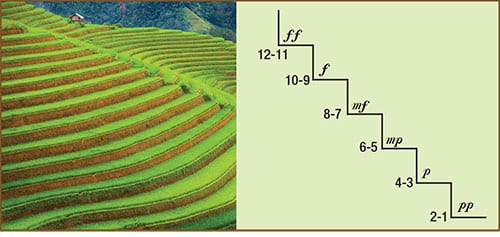

Photo by Kirby Fong

Big Bang or Fade

With music from the Romantic era, a movement concludes in one of two ways. It is either with a big bang or with a fade/diminuendo. This is true of internal phrases too. If the big bang is done correctly, musicians keep their throat open (or the vocal folds separated) until the note concludes. If the throat closes, then a glottal stop is produced. To demonstrate a glottal stop, ask students to say the words Uh Oh. At the end of the Uh the vocal folds have closed and are stopping the air. This makes a rather abrupt, unpleasant sound. The trick is to keep the throat open (or vocal folds separated) by saying Hah-Ho.

The taper or fade is achieved by slowing the air stream in an organized way. If playing with vibrato, the vibrato is stopped before the note ends so the final taper is achieved with a straight sound.

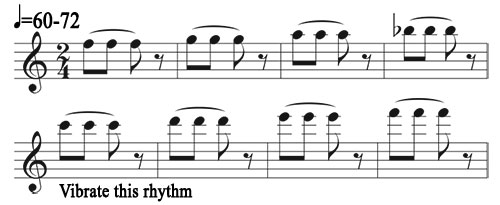

William Kincaid, the legendary principal flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra and flute professor at The Curtis Institute, suggested a taper that is terraced shaped like the terraced farming used in hilly areas. He suggested the exercise in the box below where the note is tapered for 12 counts. Since there are six dynamic markings that are used most often, he suggested playing each dynamic for two counts.

This exercise can be done at any tempo and is a valuable way to count and organize the taper. When using vibrato, it is stopped a little bit before the end, perhaps on count eight or nine, and the taper is concluded with a straight sound.

When finishing the taper on a final note of a piece or movement, the conductor and the ensemble should remain still so it seems to the audience that the taper is continuing for an even longer time. This is called, “Holding your audience.” Check the notation carefully. If the final note is a dotted half note, the taper is completed before the next downbeat. If the final note is a dotted half note with a fermata, continue the taper down as far as you can within reason.

Practice with a tuner when tapering. The tendency is for the pitch to go flat. If flatness is detected, slightly increase the air speed and adjust the angle the air.

A taper over 12 counts is a luxury that happens infrequently. Many tapers are executed in half a beat or so. The following exercise explores quick tapers while vibrating. One of my flute students compared a perfect tapered ending of a note to the swirl on the top of a soft serve ice cream cone.

Two-note slurs are also good to practice quick tapering. These two-note slurs are played strong/weak and are sometimes called sigh figures because in text painting the notes correspond to words like lov-ing, be-ing, kiss-ing. Most instrumentalists who use vibrato tend to vibrate on the first note, but neglect vibrating on the second which makes the note ending less beautiful. Have students practice vibrating on the first and second notes, making the second note softer than the first.

Passing a Phrase

Many compositions are written where one section plays a phrase and then it is passed off to another section. The goal is to make this transition from one section to the next seamlessly. Things to consider when making this transition are tempo, pitch, dynamic, and tone color. For tempo, practice with a metronome ticking the subdivision of the beats, remembering that the last note for one section will be the first note of the next section. In many ways, practicing transitions is one the of most efficient ways to raise the level of an ensemble.

The tuner is helpful in fixing pitch issues. If students know the pitch tendencies of their instrument and the pitch tendency of the instrument they are passing to, things generally go better. Of course, as Michel Debost (legendary flutist and pedagogue) said, “Your two best professors are ear no. 1 and ear no. 2;” so listen, listen, listen. When passing a phrase, consider the dynamic. If the clarinets are passing to the flutes, then both sections should play at the same dynamic on the passing notes.

Using tone color in passing is perhaps the most sophisticated skill of all. I remember hearing the Philadelphia Orchestra woodwind section passing a scale from high to low. They were so skillful in passing that it was almost impossible to tell where the flute passed to the oboe, the oboe to the clarinet, and finally the clarinet to the bassoon. Of course, they used sub-dividing and pitch, but each player changed tone color to blend into the next instrument. Changing tone color means adding or subtracting the amount of core there is in the sound.

Metronome Track

When playing Romantic era etudes with the metronome, students quickly realize that it is difficult to play a stream of sixteenths and breathe at the end of the phrase as time (metronome) does not stand still. Usually, the student does not close the phrase gracefully, but tries to continue playing while taking a breath and staying in sync with the metronome. This means that a note or two do not sound. Teaching the concept of turning a phrase means that in the performance of Romantic era music, a player takes time to close the phrase (slight slowing), breathe and continue. Introduce students to the idea that Romantic music is about singing, and when singing, we breathe. Many contemporary lyrical, slow movements are played in the Romantic style.

Focusing on the first note of a composition as well as the last improves the impression that an audience has. Focusing on internal note beginnings and ends raises the level of musicianship for both performers and listeners. Success often happens just by making students aware of musical goals. This is true for marching band performances as well as concert settings.