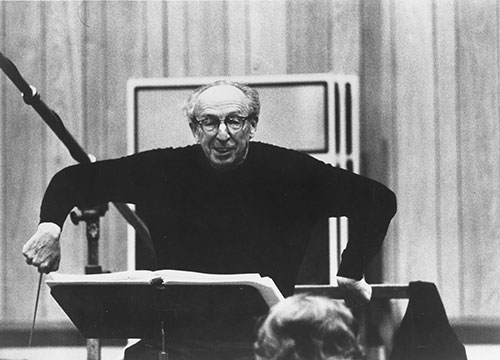

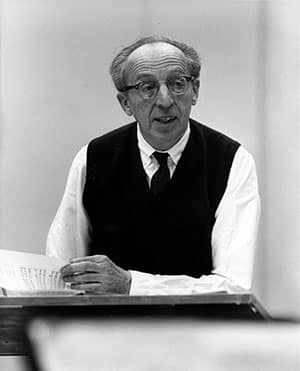

Editor’s Note: This interview with Aaron Copland (1900-1990) originally appeared in the November/December 1979 issue of Accent, ©1979, The Instrumentalist Publishing Company.

Aaron Copland is a 79-year-old whirlwind who has not only composed some of our modern American masterpieces but has also worked feverishly at dismantling the barrier between the composer and the audience by lecturing, teaching, organizing festivals, and writing books.

He is highly regarded as a composer who ingeniously combines various elements of native American musical forms into large works. His music not only borrows from, but delights in using jazz and blues motives, fiddle tunes, square dances, Mexican folk songs, revivalist hymns – anything representative of our culture. He has a particular genius for using all of these influences without sounding cliched. The respect accorded him has been based on his refusal to be stuck in one category and his charm is seen in the enthusiasm and joy he brings to his work.

When we asked Aaron Copland about the composing process, he told us that you go about writing the music by getting musical ideas that seem full of possibilities for development.” He added enthusiastically, “You might get a music idea and think ‘This is pretty, but what am I going to do with it? It doesn’t seem to suggest any particular use.’ But an idea that seems to have within itself the possibility for development, for being combined with other ideas – it’s these nuggets of expressivity that you hold onto for dear life – you write them down immediately so that you won’t forget them.

When we asked Aaron Copland about the composing process, he told us that you go about writing the music by getting musical ideas that seem full of possibilities for development.” He added enthusiastically, “You might get a music idea and think ‘This is pretty, but what am I going to do with it? It doesn’t seem to suggest any particular use.’ But an idea that seems to have within itself the possibility for development, for being combined with other ideas – it’s these nuggets of expressivity that you hold onto for dear life – you write them down immediately so that you won’t forget them.

Now, I compose at the piano. People used to think it was rather shameful for a composer to admit that he used an instrument to write his music. But one day Stravinsky said he always wrote at the piano, then it became ok.

“Unfortunately, a young person just starting to compose is liable to be mixed up by this. He thinks that all you have to do is go to a piano and by chance you put your hand down on a chord and it’s the right sound. But it doesn’t work like that. Composing music doesn’t happen just by chance; something is guiding those ten fingers of yours. But of course, a musical idea is just a musical idea. You’re not a real composer if you don’t know what to do with it. So even though you may use an instrument when you write, that doesn’t solve your problem of how to write a piece of music.

“I suppose the formal structure of a piece of absolute music (music that has no story) is one of the most challenging things that the human mind can battle. How the devil does a piece start with a few notes here, and half an hour later, end over there? How do you get all of those notes so that they have a logical flow: that they are focused around a subject; and that they make sense together?

“That’s very mysterious indeed. All of the counterpoint exercises you do and rhythmic studies and so forth will be a help, but they will not solve that final problem of putting a piece together from beginning to end. Even a simple piece has to make sense.

“However you write it, the end product is always the result of a considerable amount of inspiration, calculation, and knowledge, as well as things you were taught, things you remember, and things you have experienced when you’ve listened to music. An enormous amount of background material is there for everything you create.

“The experience of hearing one of your works performed in public is important. The piece that you play to yourself at home in your studio is one thing, but to sit and hear it with an audience – that’s different. The piece doesn’t sound the same as it does at home. Those long parts that you thought were maybe too long will get their real test when they are played before an audience.

“Composers must be able to think about their music as if it were written by someone else. That’s not so easy to do. Many composers fall in love with their own work and lose all sense of objectivity. It’s very valuable to get away from what you’re doing and for a while and forget it. Then when you come back you can think about it freshly. That’s extremely important. I know there are great composers who have to write an entire piece all at one time with wild inspiration, or they can’t compose at all. But I’m the other type. I need to get away from it, because the music always seems different when you come back.

A poet once wrote: ‘Two dangers never cease threatening the world. One is order, and the other is disorder.’ You must indicate spontaneity, but in the writing, the composing of the music, you have to hang on to control. The whole creative act is almost symbolized in that sense of not being in control, and yet being in control. If you control yourself too much, you never get those bright ideas that come from uncontrolling yourself.”