My initiation as an instrumental music teacher started in Cassville, Missouri. I look back with fond nostalgia and sincere appreciation to my students at Cassville Public Schools who gave me the first fertile soil to grow as a teacher. I graduated from college in January 1969 and had only a few days to prepare for the first rehearsal with my new students. My college training had been excellent. I could play the Mozart Bassoon Concerto, had a basic knowledge of the great band works, read many articles in The Instrumentalist on rehearsal techniques, and had all the conducting patterns from the Max Rudolf conducting text memorized. I thought I was well prepared for my first rehearsal with the Cassville Middle School 90-piece band.

The night before our first meeting I decided that Nelhybel’s Festivo would be a good choice to start the rehearsal because it was fast and exciting and would appeal to the energy of young musicians. I stood in front of the mirror working on the basic 4/4 conducting pattern needed for Festivo. I thought my patterns for the prep beat, light staccato, full staccato, marcato, and expressive legato were clear and would impress my students with their sensitivity. Boy, was I proven wrong.

The next morning my students marched into the band room, looked me over, got out their instruments, took their seats and waited for me to say something. After an introduction and summary of my background, I announced that we would start with Festivo. With much shuffling through their folders, they found the music and we were ready to begin. I gave my prep beat and a sharp downbeat but was answered with dead silence. Undaunted, I gave another silent downbeat, and this was also met with silence.

Slightly confused, I explained in my most erudite manner the purpose of the preparatory beat and the ictus to start the piece. The students’ eyes glazed over after hearing this mountain of minutiae, and at this moment my confidence in my conducting technique began to melt. I was saved from my dilemma when a little girl in my flute section spoke up, saying “Mr. Knight, you’re doing it all wrong. Our old band director would always say ‘one-two-ready-play,’ and that would start us off.” She continued her explanation. “And he would always hit on the stand real loud with his baton for the beat, and that’s how we would stay together.”

“And sometimes he would sing the way the music goes, so we could imitate it,” piped in the piccolo player, smiling with fondness for the good old days. At this point, the sickening realization hit me that my students couldn’t count, never watched the conductor, and were taught by rote. All the fancy stick waving I gleaned from the Rudolf conducting text meant nothing to them. The two gold standard conducting quotes from Hector Berlioz – “a group that does not watch the conductor has no conductor” and “beating on the stand is the most barbarous thing a conductor can do” – had become unvalued, tarnished heirlooms. I was determined not to beat on the stand, and I was determined to teach my students to watch me. I would prevail. Thus began my first day of teaching.

During my planning period later that first day, I hurried to the band library to check on method books for teaching rhythmic counting. Unfortunately, the one available option seemed too abstract, explaining rhythm in mathematical relationships that sounded more like a recipe for cooking goulash: “In 4/4 time it takes two half notes to make a whole note, two quarter notes to make a half note, two eighth notes to make a quarter; two 16ths to make an eighth and four 16ths to make a quarter.” This continued ad nauseam.

I wanted to formulate a plan for teaching rhythmic counting that would be practical and consistent for grades 5-12. The following weekend I read everything I could find about rhythm and was finally rewarded in Paul Creston’s informative book, Principles of Rhythm (Belwin Mills, 1964). Creston defined rhythm as “the organization of duration in an ordered movement,” which closely matched the Harvard Dictionary of Music definition as “durational quality in music.”

From this enlightened definition I concluded that students have difficulty when introduced to rhythms as fractional units instead of as flowing patterns of duration motored by internal pulsations. There is a major difference between counting rhythm and feeling a rhythmic flow that enlivens the music with purpose and direction. Therefore, my challenge, as I saw it, was to teach my students a counting system that would explain how rhythmic durations are organized in a way that flow to the next beat in a forward motion, creating music that sounds alive. Rhythm problems are simple to solve when taken out of context. The crux of the matter is to go from the intellectual counting of rhythm to the internalization of the rhythm.

A general rule of music education is to meet students where they are and then teach them in a logical manner what they need to know, going from the known to the unknown. Or, as Francis McBeth eloquently advised new band directors: “Know your stuff, know whom you are stuffing, and then stuff them in a sequential manner.”

Before teaching my students the basic principles of rhythmic counting, I had to teach physical ways of feeling the beat internally. Without this knowledge of feeling an internal and consistent beat, a counting system would be entirely intellectual and unconnected to a rhythmic pulse coming from within the body.

Searching through familiar band music, I wrote out basic rhythms found in middle school music and put the rhythms on flash cards. However, following the esteemed Pestalozzian system of teaching sounds before sight, I first drilled students on listening and repeating. I would play the selected rhythm on the bass drum and students, without seeing the rhythms on the cards, had to imitate the pattern, reinforcing the pulse internally by clapping or singing. I incorporated these drills on internalization of rhythm over a course of several weeks, expanding them to include counting, marking the flash cards, and understanding and repeating the basic conducting patterns.

I also believed it was essential for students to realize that a pattern of notes is simply lifeless beats upon a page. I made certain to play the rhythms we were studying with varying dynamics from p to ff, different tempi, and also with different articulations, such as staccato, marcato, and legato. The students clapped the correct rhythm with its correct style back to me. We repeated this process until the majority of students could do it correctly.

I then passed out the flash cards of rhythm patterns I had been playing so students could see the actual notation. To emphasize the feel of the forward, steady pulse I wanted students to internalize, I had a drummer beat the bass drum in a steady four-beat pattern while I played the patterns from the cards on the snare. For a variation of this drill I designated a section of the band to clap the steady pulse while the rest of the band clapped the patterns from the cards. I then switched the assignments so that each student had repeated both the steady pulse and the pattern.

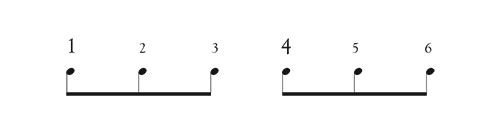

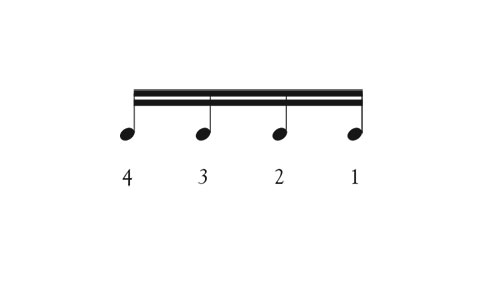

When I felt that the students were fully aware of the moving frame-like structure within each measure, I asked the students to listen for the internal pulse of the beats and mark it with a vertical line above the rhythm.

.jpg)

Clapping is certainly a good aid to teaching rhythm, but it does not show duration, which is essential as students encounter different note values. Remembering Paul Creston’s definition of rhythm, I now asked students to sing as we observed both the internal pulse moving forward and the duration of notes within that pulse. I had sing the rhythm on concert F, using the syllable tu, which is the syllable I would later use in teaching tonguing techniques. Again, I would have part of the band sing the patterns while the other students marked the notation with vertical lines, alternating so that all students participate in both singing and marking.

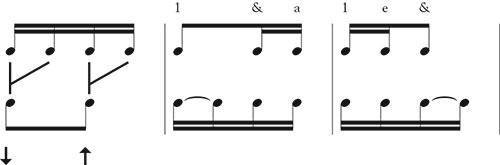

We next expanded our markings from just vertical lines for the pulse to also using a horizontal line over notes to show duration over notes to show duration in anticipation of the following step, counting rhythm.. I would have the students use the following graphics in marking the music:

.jpg)

Eighth notes drive much of the middle school band literature forward. On the and of beat four I drew a horizontal arrow that show that the music is still moving forward to the next measure and is not static. Having students draw in this horizontal arrow at the end of special places in later music to be learned encourages players to keep going and is a good cure for the barline paralysis.

.jpg)

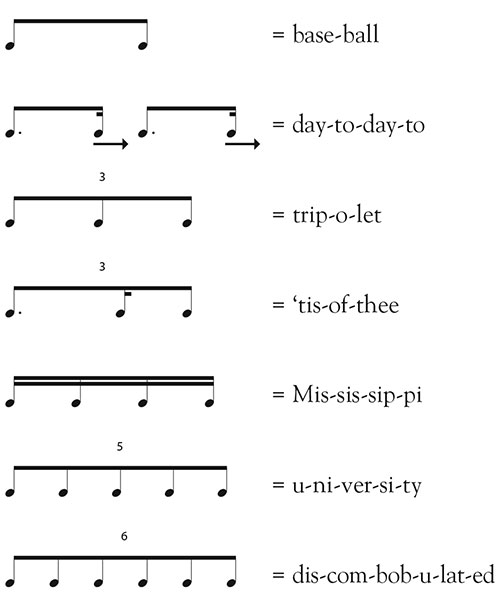

For those students who remain deficient in rhythmic counting, I suggest using words to define specific rhythmic figurers. These aids are called mnemonic aids and use words that fit the rhythmic figures represented.

It is recommended that mnemonic aids be used only as a crutch for a short time and then discarded after serving their purpose, which is for students to understand how to count the rhythm correctly and feel the rhythm internally.

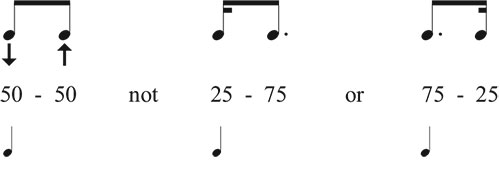

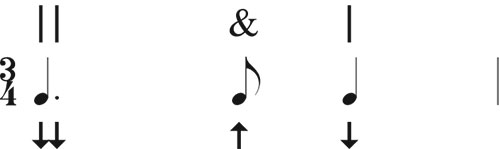

After singing, I introduce a drill of foot tapping. I usually tap with the right foot but some directors prefer to use the left, so that foot tapping does not jar the instrument while playing. It is important that each foot tap remains steady with the bass drum and evenly divided. There should not be a fast rebound of the foot; the duration of moving down and up should be equal. The foot is down and up in equal measure, not held down and jerked up, or suspended up and suddenly tapped down. I found the following visual for representative division of weight helpful:

Band directors may have different ways of counting, but it is essential that teacher and students be consistent and are able to enunciate the counting clearly and correctly. I find it helpful to remind myself and my students that music is either a song or a dance. If it is a song, like a ballad, the counting should be in a smooth connected style and all the notes seem to touch. If it is a dance, like a march, the counting should be in a marcato, separated style.

Another of my musical objectives for students to understand different rhythms was to teach them the basic conducting patterns for 4/4, then 3/4 and 2/4 using familiar Christmas and folk songs. This would also teach them to take their heads out from the stands and watch me as I conduct.

To simplify the directions for teaching the 4/4 patter, I would use classroom geography, saying, “Make your first beat point to the floor, the second beat left to the door, the third beat right to the window, and fourth beat to the ceiling. We practiced this pattern to the rhythms of Joy to the World and Deck the Halls. Students caught on quickly to the floor-door-window-ceiling pattern and felt important conducting music.

From there, I showed students the similarity of the patterns by eliminating the door for 3/4 and then the window for 2/4. We conducted to Silent Night and We Three Kings in 3/4, and for 2/4 we used Yankee Doodle and Camptown Races. This was a good chance to reinforce rhythms, including dotted quarters and eights, dotted eights and sixteenths, and syncopation.

Teaching students how the conducting patterns relate to the basic rhythm patterns accelerated learning and was an invaluable aid to sightreading. In addition, students fell in love with learning how to conduct to the point that I had two student conductors each on the spring concert from the elementary, middle, and high school bands.

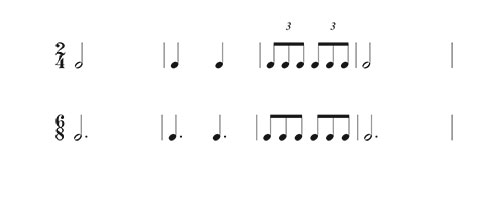

A greater challenge for the students was understanding 6/8. Using the known-to-unknown technique I started with a slow 6/8. We reviewed Silent Night in 3/4, then I rewrote it in 3/8, having students conduct a three-beat pattern while singing the rhythm. Then, I told students to erase the barline between 3/8 measures, because two measures of 3/8 made one measure of 6/8.

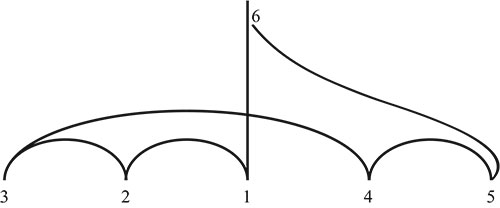

I taught students this six-beat conducting pattern, emphasizing that it was mostly horizontal, and the music should flow the same way.

Most beginning method books introduce 6/8 by comparing a fast 6/8 to 2/4.

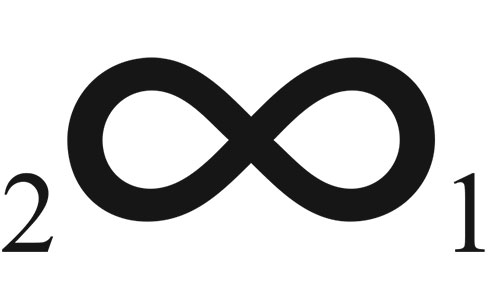

This approach is too vertically focused. I never realized this until I read Percy Grainger’s explanation of 6/8 on the first page of the Lisbon movement from Lincolnshire Posy: “Brisk with plenty of lilt, which means beats one and four are much heavier than beats three and six.” A graphic representation of Grainger’s suggestions would look like

and is best counted 1-la-le 2-la-le. To further highlight the horizontal nature of a good 6/8, I changed the conducting pattern to a sideways figure eight,

which worked well with the counting system to give lilt to the 6/8.

A musical tone has three parts: starting tone on time, sustaining the tone in time, and releasing the tone at the right time. Before starting the tone again, the music must have a chance to breathe, which the composer accomplishes by inserting rests. As Mozart said, “The music is not in the notes, but the silence in between.”

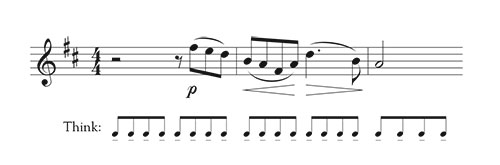

During the silence between notes, students should concentrate on the rhythmic and expressive subdivision for an appropriate interpretation of the music. To focus on rests as a dramatic and expressive element in music, I would play Toscanini’s recordings of the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and a melody from the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony so students can learn how professional musicians handle rests. With the Beethoven, telling students to think about the subdivision one measure before the entrance will produce a precise attack.

In a work like the Tchaikovsky, students should think of legato eighth notes before the entrance.

A general rule to follow with music starting after the count is to prepare the entrance with the appropriate subdivision. If the music has a 16th-note melody, think of a 16th-note subdivision. One good example of this is the oboe and clarinet 16th notes in Holst’s First Suite. This entrance is usually rushed, but if students are thinking about the 16th-note subdivision one measure before the entrance, it will be played correctly. Drawing a vertical line over the first beat of their entrance also helps.

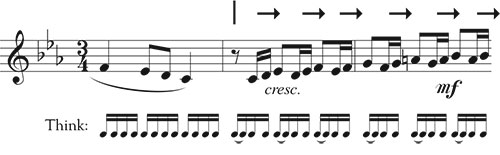

Playing after-beats without dragging the tempo also proves problematic for middle school students. Have the students verbalize the rhythm without the rests and use the bass drum and snare to reinforce the muscle memory. Then have the bass drum provide the pulse and snare the staccato 8th notes, and when the students enter on the after-beats have them play no longer than the snare staccato eighth notes. Marking the beats with a vertical line also helps.

The next fall I started teaching these rhythm concepts to my fifth grade students during the two-week wait for their instruments to arrive from the music store. I gave each student a percussion instrument on which to learn the basic rhythms on the rhythm cards. By incorporating clapping, foot tapping, singing, counting, and conducting, they received a firm foundation and understanding of rhythm and were able to progress rapidly, which allowed me more time to concentrate on teaching the other basic fundamentals of tone production, fingerings, embouchure, and hand position.

* * *

Common Rhythm Problems

Sixteenth notes counted with 1-e-&-a are usually rushed by students. To slow them down, have students count them 4-3-2-1 or anchor them to eighth notes.

The dotted eighth-16th rhythm is often played as a triplet. Have students subdivide.

or

Triplets are often played as two 16ths followed by an eighth because when students count them using the word triplet, they say it too fast, rushing the first two syllables. Have them pronounce it as trip-o-let.

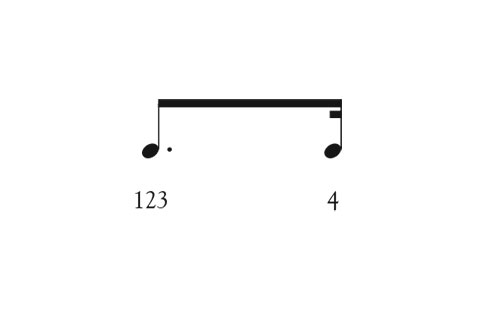

This is the most misplayed rhythm in 3/4 time:

Have students think of the dot as beat two and draw a vertical line over it. Another option with foot tapping is to have them step count two on the dot (beat two) and then move up on the eighth note (the and). Remind students that this troublesome rhythm is the one we know so well from ‘Tis of Thee and Silent Night.

Vertical lines

Tapping