Kids who don’t learn to swim well can end up as adults afraid of water deeper than a puddle. My siblings and I spent many of our childhood days in the water, honing our swimming through a well-run summer program at the local high school that continues today. When I signed up my stepson for the program I knew he could make substantial progress over five weeks.

Eliott previously took swimming lessons as part of summer camp, but the activity seemed more like playing around than swimming. This summer’s classes were different, taught by veteran high school coaches and a team of endlessly patient teenage students. Eliott sometimes lets his confidence outrun his abilities. When we work on reading books at home, he reminds me, “I already know how to read.” I worried that he felt the same way about the pool.

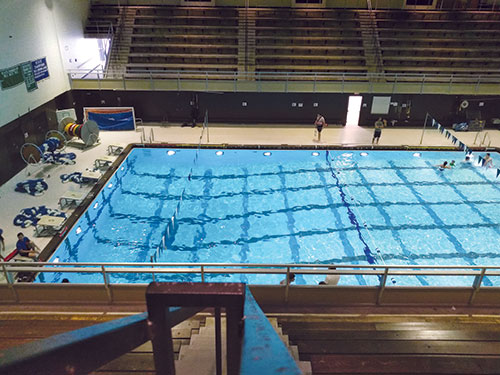

The lessons got off to an inauspicious start as we navigated through a series of locked doors at the high school, a surly security guard, and a deserted locker room. I steered him past the lockers and showers and onto the pool deck. At one point, he asked if we should just go home. I shook my head and left him with twenty kids and a dozen instructors. I climbed into the spectators’ balcony to see what would happen next.

Glancing over at huge banners listing dozens of state titles dating back to the 1940s, I noticed that all of the high diving boards were gone. These had been a mighty obstacle to conquer during free time at the end of my lessons. Almost everything else felt the same as I remembered.

I watched as Eliott jumped into the pool and started to swim. His technique was ragged after months away from the water. The instructors placed him in level 1 for beginners, a big relief for me. Just as a military recruit starts at the beginning in basic training, I wanted Eliott to build his swimming skills with the fundamentals. False confidence doesn’t float. When he passed the first level and moved up a few days later, he was exultant. I mentioned that moving up meant an automatic trip to Dairy Queen.

Over the next several weeks, I sat mesmerized in the humid gallery. I came to watch even on days when my wife was covering the lesson. The security guard started saying hello, and locked doors were now propped open for the parents.

At times, Eliott looked tentative on the pool deck. He often waited by the locker room door until encouraged by a teacher to join his group. Once the lesson began, however, he was all business. Whether or not a particular lap across the pool showed improvement, he hopped up the ladder, walked confidently back across the pool deck, and jumped in ready to go again.

One day, I could tell he was going to pass to level 3. The head instructor, a tall coach with a booming voice, stopped to test some students for the next level. Eliott’s first attempt looked pretty good, far better than a week earlier. The coach urged him to try one more time. As he swam across the shallow end, I could feel my shoulders mimicking the slight rotation of each stroke. The coach roared his approval as Eliott climbed the ladder. The boy smiled and held up three fingers as he passed below my regular seat in the gallery.

My teenage niece, who had taken the same swimming lessons when she was younger, reminded me that level 3, which incorporates breathing to the swimming motion, takes a long time to pass. At this point, however, I didn’t care if he moved up again this summer.

Watching Eliott’s lessons reminded me of my early efforts playing the trombone. I remembered the long hours in the living room repeating the same scales and easy exercises. Although music and swimming can be group activities with a social component, much of the hardest work happens alone. Progress in both can be incremental and imperceptible.

As Eliott struggled to master the gentle sideways turn of the head, I fretted that he might get discouraged. I told him that passing to level 4 had two parts: mastering the technique and showing confidence.

“You need to show that if they put you in the deep end, you won’t have a problem.” Thinking of his confident walk during lessons, I told him to swim with just a bit of swagger, a word he did not recognize.

“Is that a good thing or a bad thing?” he asked.

I replied, “A little bit of swagger is a good thing. Too much swagger can make a person seem like a jerk.”

The final week of lessons arrived and studying Eliott’s nearly identical trips across the pool remained a daily pleasure. I was disappointed to miss one of the final lessons due to an appointment. When I saw him later, I asked if I missed anything. Barely looking up from his computer, he mentioned in passing that the coach had moved him up to level 4. Then, with pride in his voice, he told me everything about it. I suspect that the success of this confidence-building summer will ripple for a long time.