Tempo maintenance does not refer to simply keeping a steady pulse; it means flexible internal maintenance of musical time as it develops, proceeds consistently, and sometimes shifts purposefully during a performance. As the size of an ensemble increases, so too does the probability that musicians will be out of sync with each other at times. Students need to know what causes this problem and build effective skills for addressing it. Percussionists have ample opportunities to make or break a piece based on their tempo control, so helping them sharpen their skills is especially important.

Using the Metronome

Using a metronome might be the most common approach to developing consistent tempo during practice. Many students might think of metronomes only in quick, numerical terms, such as “I need MM = 76” or “Set that quarter note to 112.” Using the metronome to build internal tempo skills fully, however, requires the use of its functions more thoroughly and creatively.

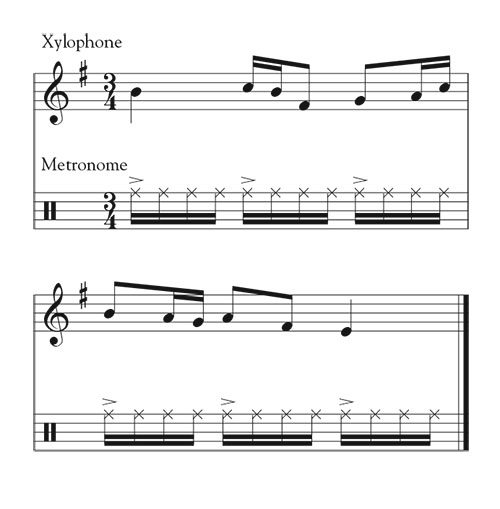

Any metronome that provides divisions and subdivisions of the beat can help. Perhaps the simplest example would be setting the machine to provide all relevant subdivisions of the beat with an accent on the main pulse. For example, if a student is playing a xylophone passage in 3/4 that includes quarter-, eighth-, and sixteenth-note combinations, set the metronome to play constant sixteenth notes with an accent on every quarter note.

The advantage to this aural input is that every note the student plays should line up with a tick from the metronome. This approach boosts rhythmic precision by providing alignment feedback four times as frequently as a quarter note would have done.

Metronomes also become musical partners when they play notes that students do not. We can set them to provide placeholders for students’ rests, creating an overarching interlocking texture, as seen in the example below.

When students play with this type of metronome accompaniment they learn to feel the offbeat eighth note as a phantom part of their pattern. Again, precision increases because reliable additional information is made audible.

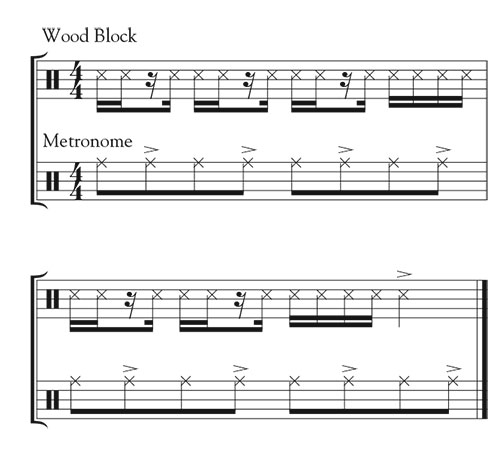

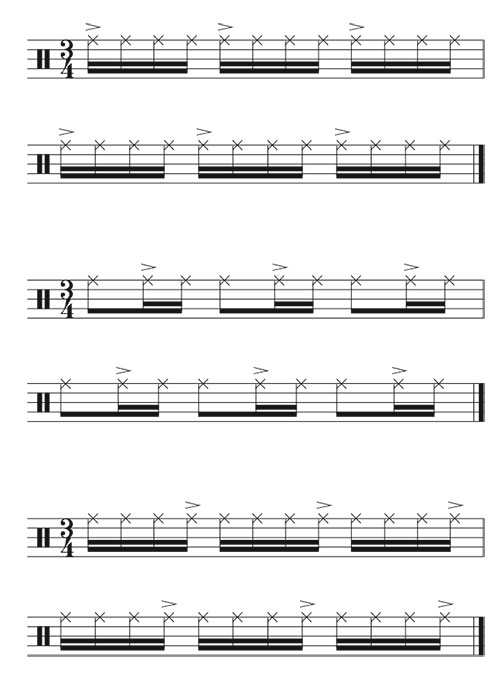

A common criticism of metronomes is that they sound rather mechanical. Students can be gradually lured into playing mechanically themselves if they begin to rely too much on the machine during practice. To address this challenge, students can be creative with how they set the metronome to help them play more stylistically. For instance, the first of the three examples below shows a simple subdivided pattern in 34 useful for general playing. The next two examples show variations that might correspond to the style of a passage students are rehearsing. If the music is rather light and buoyant, requiring your percussionists to stay on top of the beat, placement of the accent on the offbeat, as in the second example, might help. If the piece has a strongly syncopated feel, with a bass line that moves in anticipation of the pulse rather than right on the downbeats, the third example might be best.

No matter how artfully your students use the metronome in practice, they need to detach from it well before a performance. As simple as it might sound, the most direct way to do this is by alternating repetitions with the metronome and without. Frequent and rapid alternation helps students learn to supply the metronome’s part internally when it is physically absent. This not only helps them prepare for the performance at hand, but is actually the whole point of using the metronome in the first place – gradual development of internal tools by way of external tools.

Not every scenario can or should be solved with a metronome. Most teachers would probably agree that some use of this tool is warranted and even necessary at times, but resist the urge to turn it on every time the tempo starts to slide or shift, and especially when it is already steady. If we use the tool only when truly needed, in wise and creative ways, students will pay closer attention to it and gain more from the experience.

photo by Matheus Bertelli

Building the Internal Clock

Using the metronome and internalizing it is one way for students to build their musical clocks. Interacting with various tempos in daily life is another. Encourage students to become acutely aware of pulses they encounter throughout the day, such as the periodic cycle of fans or air conditioners, the oscillation of windshield wipers, the beep of a street crossing signal, or the rhythmic calls of birds in conversation. With just a few examples they will quickly discover various meters, strict and consistent tempos, and slight shifts in time, all of which are helpful for building tempo maintenance skills.

Students can interact with these naturally occurring tempos in several helpful ways. First, they should notice regular groupings of beats, synchronize to them, and discover the basic parameters of what they hear, such as number of pulses in a cycle or contrasts in emphasis level of beats. Students can also sing or play tunes they know that fit each tempo. This is a great way to practice matching what they hear and what they know. Finally, they can improvise on what they hear. For example, they can create a beatbox funk groove to fit an air conditioner pulse, a fast oom-pah pattern of knee tapping to engage the windshield wipers, creative physical subdivisions in their gait as they cross the beeping street, and an internal third voice to chime in on the bird conversation. The point of all of this is for students to generate musical time in diverse ways according to various external stimuli – the same thing they do in their ensembles.

Internal Subdividing in the Moment

Internal subdivision follows naturally from both metronome practice and daily stimuli. Students can apply it gradually and methodically as they build their musicianship through long-term audible practice. At any moment, however, players should be mentally prepared to supply subdivisions independently and internally, especially when sightreading something new or performing something for which they have had very little time for systematic practice. Getting in the habit of dividing and subdividing the beat is crucial for precise entrances and confident rhythmic placement.

The goal is for students to be able to subdivide while they are playing. As rhythms become simpler, internal subdivision remains a crucial factor and perhaps becomes even more so. For example, if students playing bass drum and cymbals are to play a forceful downbeat together (a typically unforgiving musical task), they would do well to subdivide the beats leading toward that entrance, especially if the music is shifting tempo in its approach. Sometimes the subdivisions will be played by other instruments; otherwise, the percussionists will need to generate those subdivisions mentally as they track the larger beats. Students may judge this to be tedious or unnecessary at first, but describing and modeling it as doubling or quadrupling, for example, their chances of playing precisely together will help them see how beneficial it is.

Singing the Other Parts

This final strategy is difficult, but highly rewarding. Percussionists generally use their hands and feet to play, leaving their voices free. Have students sing the other parts while playing. For example, in the final strain of The Stars and Stripes Forever, the battery percussionists mostly maintain a steady pulse on the bass drum and cymbals and repetitive five-stroke rolls on the snare drum. They may play these parts as if in isolation, focusing on their sound and alignment within the section, while thinking of themselves as the time machine and watching the conductor carefully. All of these are noble aims, but the real music-making happens when they are paying attention to the rest of the ensemble sound. Are they hearing the soaring melody, the trombone countermelody, and the piccolo filigree loud and clear as they shape those consistent beat patterns?

Singing, humming, or even grunting out other parts can be tremendously helpful for a student anticipating a large downbeat on the tam-tam, maintaining a tricky groove on the drumset, or phrasing a syncopated triangle passage. They may find it doubly challenging at first, because it is at least twice the effort. However, that extra musical effort will make their playing more effective in the moment and will eventually develop into an added long-term benefit. They will no longer struggle to pay attention to the other parts, but will be using those parts to improve performance of their original playing assignment.

This can be practiced away from an instrument. Students might sing the sustained clarinet melody to themselves as they tap out the complex snare drum ostinato on the bus ride to school, or hum the descending tuba line as they air drum the ritardando timpani part while waiting in the lunch line. The next time they pick up the sticks a lot of their internal ensemble work will have been polished already, so they can start rehearsal ready to contribute immediately and effectively.

Conclusion

External tools and guidance should gradually be directed toward internal control so that students are producing musical time rather than simply trying to stay with it. The suggestions provided here are aimed specifically at percussionists, but many of them could be applied to any instrumentalists.