I am not surprised when my university students come to lessons with the same questions and concerns I had in school. I feel very fortunate that I was taught to keep a practice notebook from an early age as it has helped me so much with both my playing and teaching over the years. As a ten-year-old beginner in Minnesota, I studied with Claudia Schnitker who gave me a template to fill out each week. I recorded how much I practiced each day, which pieces I practiced, and any frustrations I experienced.

When I entered the Interlochen Arts Academy as a sophomore, Tyra Gilb, the flute professor, asked each of her students to fill out a similar sheet, although it was more complex. There was space for a practice log, pieces I practiced, recordings I listened to, what auditions or competitions I was preparing for, what I hoped to achieve that week, how I intended to practice in order to achieve those goals, and what improved with practice. These practice sheets not only helped my practice sessions but clarified improvement throughout the school year. They taught me to organize my time and critically analyze my playing.

When I entered the Interlochen Arts Academy as a sophomore, Tyra Gilb, the flute professor, asked each of her students to fill out a similar sheet, although it was more complex. There was space for a practice log, pieces I practiced, recordings I listened to, what auditions or competitions I was preparing for, what I hoped to achieve that week, how I intended to practice in order to achieve those goals, and what improved with practice. These practice sheets not only helped my practice sessions but clarified improvement throughout the school year. They taught me to organize my time and critically analyze my playing.

Keeping Organized

As a flute professor at a state university, most of my days are quite full. From woodwind quintet rehearsals to lessons, advising, and meetings, many work days run from 8 am until 11 pm. Making a list of what I need to accomplish each day and each week helps me make the most of my time and keeps me motivated.

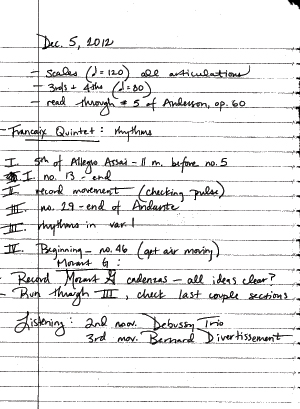

A typical notebook entry might include: Practice all major and minor three-octave scales (q = 120), all thirds and fourths (q = 80), and Andersen, Op. 60, No. 5. Practice all marked places in the Francaix Woodwind Quintet slowly and in rhythms. Record Mozart Concerto in G, K. 313 cadenzas listening to be sure all ideas are clear. Play Mozart Concerto, movement 3, by memory. Listen to Debussy Trio, 2nd movement and the 3rd movement of the Bernard Divertissement.

A typical notebook entry might include: Practice all major and minor three-octave scales (q = 120), all thirds and fourths (q = 80), and Andersen, Op. 60, No. 5. Practice all marked places in the Francaix Woodwind Quintet slowly and in rhythms. Record Mozart Concerto in G, K. 313 cadenzas listening to be sure all ideas are clear. Play Mozart Concerto, movement 3, by memory. Listen to Debussy Trio, 2nd movement and the 3rd movement of the Bernard Divertissement.

Notice that this entry includes several essential practice elements including scales and thirds and fourths, the warm-up portion of my practice. Then comes an etude followed by chamber music and concerto work. I also include listening projects into the daily routine because I consider it part of practicing. I make a point to be specific about what I have practiced in terms of rhythms, slow work, or any other exercise I apply. This helps me to track and progress toward goals. For instance, to reach the printed tempo in the first movement of the Francaix I practice the straight sixteenths in dotted rhythms. (long/short and short/long). On each repetition I slowly bring up the tempo while keeping the rhythms sharp. Eventually, I will be able to play the long passage as written with confidence.

From the timetables in my notebooks, I have found that it works best to learn a new piece well in advance of a performance and then put it away for a while. A couple of weeks before the performance, I take out the piece and rebuild the tempo. There is something about shelf life that makes technical passages feel more solid.

Using Practice Sheets with Students

Because these practice sheets have helped me so much, I suggest that my students use them as well. My students come from a variety of musical backgrounds. Some have taken private lessons from age ten, while others have never taken private lessons but come from a strong band program. Before getting started, I first look at how each student approaches a practice session. During an early lesson I ask them to practice for thirty minutes while I observe. This practicing is recorded so we can then listen together and discuss how to improve the student’s practice techniques.

First, we discuss what practice techniques were done well and which were missing, the most common omission being repetition. A seasoned performer knows that playing a passage well once can be helpful, but it will not make it consistent. Challenging passages should be repeated many times. Another common problem is that many of rhythmic or note mistakes go by without concern. When students encounter a tricky spot, they should slow down the tempo to get it right. Never feel ashamed of playing too slowly.

Another common mistake students make is to play through everything at a tempo that is too fast for comfort. The tension that comes with this will appear in a lesson or performance. I suggest starting slowly and bring the passage up a couple of clicks at a time. The next day start slightly slower than the fastest tempo of the previous day and repeat the drill. There may be some days when the tempo only progresses slightly, even one click. When this happens I make sure to practice the passage in various rhythms and then bring the tempo back up from an even slower tempo.

In this learning-to-practice lesson we talk about how the practice session comments might translate into words in the journal. For example, they should write down the metronome speeds as they practice a passage and keep track of how the tempo may have changed (four or five clicks being the average) from one practice session to the next. I ask them to write down how they organized the practice time and of course write down any bad habits to improve. Entries might include relaxation techniques or a change in stance to prevent an arm or shoulder pain. Other entries could include performance practice (run-throughs of solos, etudes, or excerpts), rhythmic exercises for technique work, and thoughts on interpretation and general patience.

When a student and I review a journal, I take note of what may be lacking in an entry. When students do not feel as prepared as they would like, a little detective work in the notebook will often uncover the practice problem.

A Student’s Opera Audition

Recently one of my graduate students prepared for his first opera orchestra audition. I made a point to ask him about the context of the excerpt he was to play for me, indirectly suggesting he learn the synopses of the operas on the list and be able to remember where in the storyline the excerpt occurs.

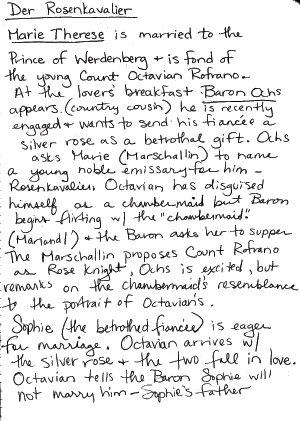

As an undergraduate at Juilliard, while preparing for my first opera orchestra audition, I recorded my preparation in one of my most memorable journals, a thick red book with blank graph paper. I associate this red journal with hours in the listening library, writing down abridged synopses, and finding exactly where in the score the excerpt could be found. In this particular notebook, I came up with a systematic way of getting to know the excerpt list:

1. Write down the synopsis in a simple way (most of the ones I found in the library were dated and confusing).

2. Listen to the entire act where the excerpt is located.

3. Write down what is occurring in the storyline when the excerpt is played.

4. Write down where (in minutes and seconds) the excerpt can be found and what the CD call number for the recording was in the listening library.

My teacher in graduate school, Robert Langevin, later advised me to prepare an audition list as if it were a list of monologues: each one a different character in a different context from the next. He said the people behind the screen are waiting for those characters, not only the technical aspects.

My synopsis of Der Rosenkavalier, in the red notebook from around 2000.

Recorded Notebooks

Recording each practice session and keeping the tracks organized on a computer or smartphone is another useful for both my students and myself. In the past students have asked about what I think of their progress on etudes. Now, they can easily refer back to earlier recordings themselves. I advise students to record run-throughs and take note of what has changed and what remains the same from one recording to the next. I also encourage them to send recordings to me in between lessons so I can reply with suggestions. As a conductor once said to me, “Listen to recordings of yourself and notice the problems in your playing. Keep focusing on the problems, and eventually you will become so aware and sick of those problems, you will never repeat them.”

Soon, this idea will be taken a step further as students will have the option of uploading tracks to Blackboard. This way everyone in the studio will be able to listen to the tracks and make observations.

What musicians do is not as tangible as a painting or sculpture. Sometimes we think we are playing in an expressive way but actually could exaggerate more. We may think there is attention to detail in practice sessions but the tendency is to leave out several important steps. Practice notebooks, both hard copy and recordings, are important to develop artistry and technique. I do not know where I would be without them.