Whether it is swimming, volleyball, tennis, singing, dancing, or flute playing, some students have a great deal of talent, some have moderate talent, and unfortunately, a few have less talent. When it comes to tone production, no matter which group students are in, they can improve their sound with a better understanding of what makes a great sound and how it is produced. Recording and listening to one’s practice daily, even if only for a couple of minutes, offers huge benefits towards creating a beautiful sound. The sound quality on a cell phone recording is good enough for daily use.

While I rarely play a student’s flute or let someone play my flute, if a student is struggling to play with a clear, focused tone, I try the student’s instrument to check that the embouchure plate is properly soldered onto the tube of the headjoint. Though this is a rare occurrence, through the years I have had a handful of students whose embouchure plates have come unsoldered. Fortunately in those instances, the solder issue was noticed by a repairman and fixed. I also check the flute to be sure all of the pads are seating correctly.

Nancy Toff writes in The Flute Book (Oxford University Press) that the flute-maker Verne Q. Powell said, “As far as tone is concerned, I contend that 90 percent of it is in the man behind the flute.” This means that if the flute is of good quality and in good condition, every player should be able to produce a beautiful sound.

In my student days, a flutist ordered a flute and waited several years for it to be made. The flute arrived, and the student learned to play well on that flute. There was no trying of other flutes or headjoints. British pedagogue Trevor Wye shared a quotation of Marcel Moyse that sums up my thinking. Marcel Moyse said, “I prefer a flute without a built-in tone. Then I can put into it what I want.” Today, many students want the flute to solve their problems.

William Kincaid, the legendary principal flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra who is sometimes referred to as the “father of the American school of flute playing,” compared sound to a softball. At the inner most core is a round cork ball which may be compared to the core or center of the flute sound. Around this ball, yards of string are wrapped which equates to the harmonic partials present in the sound. Finally, on the outside is a leather covering. This suggests that the tone should have containment and not be spread.

Core

How much core there is in the sound is controlled by the angle and speed of the air stream as it hits the blowing edge of the embouchure hole. Blowing lower on the wall creates more core or edge. Blowing higher on the wall creates less edge. To change the angle of the air, a flutist uses the lips, tongue and perhaps a very small movement of the jaw.

When playing early music on a modern flute, the results are better if there is less core, while Romantic era and some contemporary music sounds better with more core. Most theoretical technical exercises and etudes sound the best someplace in the middle. Practicing pitch bends and slurring the harmonic series offers opportunities for flutists to learn to vary the angle of air on the wall.

Harmonics

The color or timbre of the sound is controlled by which harmonic partials are the most present. This too is controlled by the angle of the air stream plus the openness of the throat, the dropping of the jaw, the position of the tongue, and the pursing of the lips. Practicing the harmonic series slurred not only promotes embouchure flexibility, but it also shows flutists how far forward the lips should be to get each harmonic partial. I prefer playing most notes throughout the range with my lips set at the third harmonic partial. An oscilloscope, which often can be borrowed from the physics department at a university, will show the harmonic partials.

Containment

Containment of the sound occurs when the air stream is even throughout the note. If the air slows or is uneven when exiting the lips, the tone will spread and there is no containment. An air stream that is too highly placed produces an airy sound without containment. Practicing even air exercises helps shape the tone.

Even Air Without the Flute

The first step in helping students with tone is to develop the skill of playing with even air. This means that there are no deviations in the air speed from the attack of the sound through the release. Flutists should be able to play with even air at any speed. It may be slower for the pp dynamic and faster for a ff dynamic. It may be faster for certain articulation marks and faster or slower for high notes versus low notes. No matter what the air speed is, the flutist should learn to blow the air out at an even speed. The following are some exercises to try with students.

• A challenging exercise to explore involves taking a cigarette paper and placing it on a smooth surface such as a wall, window, or mirror. Have students blow against the paper and try to keep it in place on the surface. If the air speed is not even or strong enough, the paper will fall to the floor. This is an inexpensive exercise to practice and is also fun to do in a group masterclass.

• Another good exercise is to blow slow, even air at the flame of a candle. If the air speed increases or wavers, the flame will immediately react.

• A child’s pinwheel (50¢ at a dollar store) can be used to chart the flow of air at different speeds from slow, even air to fast, even air.

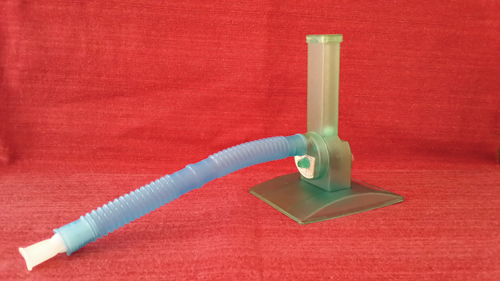

• A slightly more expensive exercise involves a spirometer ($5-10 each, but may be purchased in bulk at a reduced price.) A spirometer is an instrument that measures the air capacity of the lungs. Wind players can use one to practice playing with even air or with vibrato. With a spirometer, ask a student to blow into the hose with a preformed mouthpiece and try to keep a ping pong ball in a stationary place.

Each flutist should have their own mouthpiece and hose for sanitary reasons. When I was teaching at a university, the respiratory therapy department at the hospital was throwing away some unused spirometers, so each flutist in my studio was able to have one. Check with local health care professionals to see if they might be have extra devices for your students.

Even Air with the Flute

Before you begin, be sure that the student has good posture and that the aperture in the lips is in alignment with the embouchure hole on the headjoint. Using a tuner, have the student blow a middle D where the sole objective is to keep the needle still. It may take several tries. Do not worry whether the note is flat or sharp at this stage as the flutist is working on the basic concept of moving the air at an even speed. Control of the pitch will come later.

Practice this concept on whole-note scales (major or minor, one octave, ascending, with no vibrato), keeping the tuner’s needle still. This exercise is useful for every flutist because even a few days off from practice will diminish the ability to play with even air. Once a student is successful at keeping the needle still, repeat the process but fix the intonation. I prefer doing this exercise with a tuner set at A=440, although students should be aware that in Europe the tuner is usually set at A=442. For additional work on playing with even air, practice one-octave scales in thirds plus the one-octave major, minor, diminished and augmented arpeggios.

Speed of the Air

Generally, when a flutist has tone problems, the air speed is not fast enough no matter the dynamic or placement of the note in the range. In 4/4 meter, have a student play a dotted half note at a mf dynamic followed by a rest. In the rest both you and the student say the word blow. The student should take a sip breath after saying the word. Repeat several times so the student begins to put more air through the flute and is playing on the exhale. Repeat throughout the range. I like to think of this type of blowing as playing on the edge. I put as much air through the instrument as I can without losing control of the sound. Having students aim the sound to an imaginary target across the room while doing this exercise will improve projection of the sound.

Angle of the Air

If the tone is too airy, the air stream is directed to high. Ask students to direct the air to the left elbow. When you give this instruction for the first time, they will more than likely lift their left elbows to meet the air stream. For this to produce the best results, the left elbow should point to the floor with the left arm rather close to the body but not against the ribs. If the tone is too edgy and metallic, they should lift the air stream slightly. To change the angle of the air, flutists use the lips, tongue and perhaps a very small movement of the jaw.

Reflected Sound

Sometimes students do not know what a good tone sounds like and so have difficulty producing one. Listening to live concerts, recordings, or YouTube videos with students is helpful in teaching them what to listen for. Flutists today blow differently than they did 50 years ago because most concert halls are much larger than they once were. Tastes also change as do musical styles, so other tone colors are demanded of artists.

Joseph Mariano, the legendary flutist, often warmed up standing very close to the large glass window in his studio. I heard him practice this way day after day and wondered why he was doing this. Since I had a similarly large window in my practice room in the annex at the Eastman School of Music, I decided to give it a try. I quickly realized that he was warming up this way because the hard surface of the window’s glass reflected the sound back to him immediately, and he knew what he needed to do to play with the sound he wanted.

I like to practice at the piano with the right pedal depressed. I play a note and let the piano sing it back to me. The better tone I produce, the louder the piano rings back to me. This is also a good exercise to practice when getting ready to play with piano accompaniment because you will learn where the pitch is on each note in the range.

Projection and the Cushion of Air

With today’s larger concert halls, flutists need to play louder than they did when playing in salons and smaller concert venues. William Kincaid suggested putting a cushion of air (making the tone slightly on the airy side, but still with a core) so that the tone would project to the back of the hall. By the time the tone leaves the stage, the orchestral performers sitting in front of him had absorbed the air in the tone with their sheer presence. However, if the tone was very clear where he was sitting, it continued to get smaller and clearer as it floated out to the audience. He always told us to play to the back of the hall where the real musicians were – in the cheap seats.

Homogeneity of Sound

Each of the flute’s 39 most used notes has a specific blowing place on the wall of the embouchure hole. As a flutist moves from one to the next, whether it is stepwise or a larger interval, the tone color throughout the range should be homogeneous. Recording scale and arpeggio practice helps identify places where there are deviations. Marcel Moyse’s first exercise in the De La Sonorite was written to help flutists explore this concept. However, any theoretical technical material played slowly enough can be used to practice the concept.

Vibrato

Generally, vibrato is not something you add onto the tone, but it is part of the tone. Once the basic concepts above have been explored, then incorporate them using vibrato.

Breathing

While this article could have started with a discussion of posture and good breathing habits, sometimes it is better to practice exercises without a lengthy discussion about the anatomy of breathing. I have found that once students can do the exercises, their brains have already figured out how they should breathe to accomplish the goal.