From The Instrumentalist: February 1989

Is it possible there is an arranger whose music has been heard by almost every person in America, or whose arrangements have been performed by every jazz musician who has played in a jazz ensemble? Considering that Sammy Nestico has arranged or orchestrated music for more than 60 programs, including M*A*S*H*, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Love Boat, and Mission Impossible, and has published more than 700 compositions or arrangements for school music groups, such a statement comes close to the truth.

Now 64 years old and living near Los Angeles, Sammy Nestico has never known life without music. As a 13-year-old trombonist at Oliver High School in Pittsburgh, he knew that he wanted a career in music. Encouraged by his mother who wanted him to become a teacher, Sammy graduated from Duquesne University as a music education major. After one year as the high school band director in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania, Sammy joined the Air Force in 1951. He recalls, “I remember how much I loved the kids while I was teaching, but I also remember how much I hated the administrative details and the paperwork.”

Sammy then spent 15 years as a staff arranger for the Air Force Band in Washington, DC He was also the first arranger for the Airmen of Note, the official Air Force jazz ensemble. It was during this time that he perfected his unmistakable arranging style. For the next five years Sammy was the chief arranger for the United States Marine Band and leader of the White House dance orchestra during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. While in the Marines Sammy had his first encounter with Hollywood. “I directed the concert band on camera in the Gomer Pyle show when Gomer went to Washington to sing with the Marine Band.”

On leave from the service during the early 1950s Sammy took brief road trips as a trombonist in the Woody Herman and Tommy Dorsey bands. He says, “Tommy Dorsey was my idol. When I was in his band I just put my horn down and listened to him play. Don’t forget, before Dorsey all you heard was gut bucket trombone, and then here came that golden Dorsey sound. He was an innovator.” Count Basie was introduced to Sammy’s arrangements during this time. “My cousin Sal was playing tenor saxophone with Basie and said I ought to write something for the band, so I wrote Queen Bee and sent it in,” explains Nestico. “At 2 a.m. one morning I got a call from a band member telling me that Basie liked what I had written and wanted me to do some more charts for him.” What followed was 10 albums of original Nestico music recorded by the Basie Band between 1968 and 1984, four of which won Grammy Awards Nestico says he had about 120 charts in the band’s book by the time Basie died in 1984.

A recording session with the Count Basie Orchestra. Photo courtesy of Scotty Barnhart

Sammy recalls his relationship with Basie as the musical highlight of his life. “I think Bill was the nicest person I’ve ever met; just a good, humble person – almost shy. Basie’s band could take beautiful melodies and make them swing. That’s what made his band different from the Herman or Kenton bands. While I admired Woody and Stan for having grown musically with each decade, Basie stuck with what he did best. One trouble a lot of writers had was that they wanted to write like Basie. Basie always told me, ‘They should write like themselves and we’ll play it like Basie.’”

At the age of 44 Sammy moved his family to Los Angeles in 1968. “My wife always said that if I was going to strike out, I should do it swinging with the bat in my hand. She said that I was going to get my shot in Los Angeles even if she had to scrub floors. I believe a break is what happens when preparation meets opportunity. A break will come so it’s best to work hard and be prepared. If you should falter, then another break will come, but next time be ready.”

Sammy doesn’t have fond memories of his family’s first few months in Los Angeles, but says he owes much to the Hollywood arranger Billy May, who gave him his first break. Nestico recalls, “Margie had back problems and was in a wheelchair, my three teenage kids didn’t like California, our savings were gone, and there I sat trying to write cues for the Gomer Pyle show. Just as the water was up to my chin, Billy turned to me during a recording session and asked if I could copy a big band arrangement off an album. There was my break. He said Capitol Records was recording old swing-era tunes in stereo, so he gave me an album of Benny Goodman’s Stealin’ Apples and I went to work. Billy had to arrange eight tunes a week, so he gave me three or four to do. I was with Capitol for four years and 63 albums.”

Another break came when composer Pat Williams asked Sammy to orchestrate for him. Nestico says, “Pat would sketch out the melody and chords and then give me an almost blank sheet of manuscript paper to fill in the orchestral voicings and individual parts.” The life of an orchestrator can be unpredictable and rather grueling, as Sammy recounts: “I once got a call from Universal Studios at 5 p.m. on Thanksgiving Day to come to the studio to orchestrate the television special It Happened One Christmas, which featured Orson Welles and Marlo Thomas. I wrote all night long and was still writing when the orchestra walked in at 8 a.m. the next morning. I was still writing while they were recording at 2 p.m. that afternoon. I almost fell asleep going home on the freeway that night.”

Another musical highlight was when he started to publish his own music. “My first publications were watered-down arrangements of my Basie charts. In those days Art Dedrick was the father of stage bands, and he was just starting Kendor Music. I’ve always regretted that we simplified the first Basie charts I published. We just figured they were too hard for kids. In fact, we didn’t even publish Magic Flea for quite a while and I think it sold more than any of the others when we finally published the recorded version.”

Speaking of his current success as a published composer, Sammy says, “I’m very proud to be writing for the schools of America. I think that’s terrific. There is something exciting about being able to write simple and melodic, but not bland pieces. It’s a challenge and a thrill to write something that you know has some musicality to it and yet is playable by young people. I’ll come out of my little studio and tell Margie that I really enjoyed that a lot more than writing a professional arrangement. A lot of love goes into the music I write for kids.”

When Sammy writes for publishing companies he feels added pressure to get it right the first time. “My schedule in Los Angeles never gives me time to hear school groups play my music. It’s almost always the publisher’s promotional record that gives me my first hearing of my music, and then it’s usually only 32 bars before it fades out. As I write I can hear the band in my head, but there are a few things that surprise me when I finally hear my music played by a band.

Sammy tries to write music that musicians will want to play. “Their enthusiasm for my music will spill over into the audience and the audience will like it. I like to write a piece that has everybody smiling after they hear it. I’m a happy person, and I like to write happy music. I guess that’s why I don’t write many minor key things.” When asked to name his favorite big band compositions or arrangements, he names Warm Breeze, Basie Straight Ahead, 88 Basie Street, Satin Doll, and Sweet Georgia Brown.

Composers who influenced his style include Billy May, Bill Finegan, Bob Florence, Neal Hefti, Frank Foster, Nelson Riddle, and Thad Jones, most of whom wrote for the Basie band. Sammy now particularly enjoys the music of Bob Mintzer. “I think Mintzer’s writing and band are terrific. His music doesn’t sound like anything done before, even though he uses the same eight brass, five saxes, and rhythm section that everyone else uses. It’s fresh.”

The process of composing is not always easy for Sammy. “Two days a month I can’t get the notes down fast enough on paper, the other 28 days it’s really hard work. It’s always a process of accepting and rejecting and it’s not so much talent as it is persistence and desire. A young composer has to accept that there will be writer’s blocks. I write better music in the car than I do at the piano because when I’m in the car I can sing melodies, but when I sit at the piano I get hung up playing chords.”

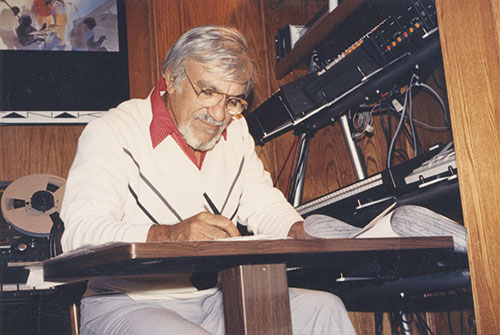

Sammy regularly uses electronic instruments when he writes. “I use a synthesizer because it’s easier, and I can use headphones; that way I can work late and not bother anybody. My son installed an 8-track tape recorder and a complete MIDI lab in my home studio. It makes writing more fun, but it takes me twice as long to put the music in the sequencer as to just write it out. It’s just fun to hear the parts played back on a synthesizer. Still, it’s not like a piano. The piano is the greatest instrument in the world.”

Sammy believes that a young musician or composer shouldn’t compare himself unfavorably with someone else. “Unfortunately, I always did this,” he says. “I’ll never forget the first time I worked with Hollywood composer Billy Byers. He called at 8 a.m. one morning and wanted me to help him write a complete show for Mama Cass, who needed the music the next day. A few minutes after we got started writing, I could hear Billy in the other room tearing off one score page after another. At 10 a.m. he was on the phone telling the copyist to come pick up some tunes. By 2 a.m. the next morning he had written three times the number of cues and arrangements I had. I went home and told Margie that after seeing Billy Byers work, I should be a plumber. That afternoon though, he called from the rehearsal to say that everybody loved my music. I felt like a million dollars. If you compare yourself to everyone else, you’ll always come out second best.”

One of Nestico’s great thrills came in 1983 when he received the honorary Doctor of Music degree from Duquesne University, only the fourth person to receive such recognition from that school. “The others were Andre Previn, Henry Mancini, and Benny Goodman – pretty good company, wouldn’t you say?” Sammy smiles.

What’s in the future for Sammy Nestico? “At my age I can be more selective about who I write for. I won’t write for nightclub acts, it’s just too limiting. That’s why I enjoy the writing I am doing now for Sarah Vaughan, Pia Zadora, and Toni Tennille: they use a full orchestra, which allows me to write exciting colors. I want to write music until the day I die. I’ve never really reached where I wanted to go, but I’ve had some good successes. You know it’s all hittin’ and missin’; I’ve done both, but hittin’ is sure a lot more fun.”