Every fall I observe a wide variety of great percussion teaching by watching various marching bands perform. I see incredible playing, but also groups limited by what the percussion ensemble is asked to do during the program. This can happen for many reasons including arrangements, ability level, and lack of a dedicated percussion instructor.

Common Arrangement Errors

Using the drumline too much as a moving drumset. Snares playing 2 and 4, tenors playing quarter notes down the drums, and basses playing a unison groove can be effective in small doses but too often becomes the main portion of what a percussion section is playing. If drumset is needed, use a drumset in the front ensemble and avoid having the battery doubling the set. That is a timing and musical nightmare. Look for creative ways to get the groove needed from the section if drumset cannot be employed. Use accent patterns within diddle rudiments etc. to create more sticking variety but still maintain the necessary feel.

Arrangements often do not have enough content. Most groups would not ask the winds to play whole notes through the full show, but frequently the percussion do the equivalent of that. The marching season is a great time to develop the hand technique and coordination of the ensemble, but this requires challenging content. I am not saying that every line has to have rolls at 200 bpm and crazy flam passages. Using the various diddle rudiments, an appropriate speed of roll for the section’s ability can improve their skills and enhance the wind writing.

Inadequate use of the front ensemble. The front can provide myriad sounds and colors to a show but often is underutilized. Too many shows feature a student playing tambourine, one playing suspended cymbal, and a third playing bells. To improve the full ensemble sound, make sure you have a good cymbal or two and a concert bass drum. These will fill out the wind sound at impact moments. In addition, a well-placed and tasty cymbal roll can be just the right sound for a phrase transition musically. Add timpani to the front, especially if you have limited low brass. Timpani can add a great deal of bottom sound to fill out the full ensemble texture. The role of timpani in pit features is also often overlooked as they are what will fulfill the bass sound and keep the sound of the front ensemble from becoming too high pitched when the winds are not playing.

Employ a variety of mallet instruments. If your program is limited in keyboard instrumentation, think about mallet selections to help blend the sounds into the winds more. For example, yarn mallets on the low end of the xylophone can emulate a marimba sound. Also adding one synthesizer (or mallet controller like a MalletKat, Xylosynth, Zen Melodic, or Mallet-

station) can open up a much wider palette of sounds from the front that can help further fill out the band sound. (Do not overuse the thunderous goo bass effect!). An electronic mallet instrument can fill in for other mallet instruments you cannot afford yet.

Try not to have the front ensemble double a wind instrument if it can be avoided. The front can be great for ostinato patterns, arpeggiated patterns, and more. These will often project better and fill out the ensemble sound more than doubling the melody in the front. When it gets to the impact, unleash the cymbals, bass drum, and tam tam. I often hear percussion and GE judges talk about bands lacking impact, and that is often because they do not fully use the front ensembles at those points in the show.

Space is good. The drums do not have to all play all the time. Save that for the most important impact moments or have a section maintaining a groove or ostinato effect while another section carries the content at different times. Think of how winds are arranged: the full wind section does not play the whole time and neither should the battery.

Use the idea of a rhythmic cadence. I am not talking about a street beat-style cadence but something similar to what composers like John Cage did in music that did not feature traditional melody and harmony. They would often speed up or slow down rhythmic structures at the ends of a musical phrase to give the effect of finality and to transition to a new idea. Too often, arrangers fall back on quarter-note triplets or even just quarter notes to note the end of a major musical event. After a while, the desired effect becomes predictable and less effective.

Find ways to make the rhythmic structure lead naturally from one phrase to the next. An increase or decrease (either can work depending on the context) in rhythmic tension can be a much more effective (and creative) way to transition between sections. One of the easiest is borrowing rhythmic motives from other points in the show or even other music that might be related to the show such as other pieces by the same composer. You can think of it as creating musical Easter eggs.

Seek out as much material on the music you are playing as possible. With orchestral music, get the full scores. Look for string lines that might not have been included in the arrangement to fill out the front ensemble parts. Find important percussion parts from the original score and include those when possible. This is also a great way to teach percussionists about these pieces and the role percussion plays in a larger concert ensemble. With pop music, look for as many versions of a tune as possible. You can usually find one with a slightly different yet very cool feel that can be used. This can also give you new scoring ideas for timbres. Look for specific effects in a piece that you can recreate in a cool way on a field. Try to do it acoustically first before settling on punching a button.

If it is a choice between a very small battery and a very small pit or having a larger version of each section, consider putting the full percussion ensemble in the pit. The amount of color they can add will be much higher there than with just battery instruments. It is also a great way to get more of the kids interested in playing mallet instruments. I would not use battery instruments in the pit or ground the battery because this causes too many balance, blend, and timing issues. Use concert drums to blend the sound more effectively. They can always get their battery fix playing in the stands at football games.

Try not to retrofit audio into the show. It is far more effective if the ideas you want from technology are part of the design process along the way. This means ideas such as leaving space when words need to be heard, knowing what sort of underlay you want throughout the show, and when to use synth doubling or effects.

Use fewer rim shots. Shots should be an effect, not a main musical idea. This is even more important if your show is in a dome, as you will hear each shot long after it is played. In addition, from a technical standpoint, students often change their approach to rhythm and stroke leading into and performing the shots, so they can also cause clarity errors around the shot. It can be an effective tool, but as with everything else, it becomes less effective in excess.

Improving the Arrangements

Better arrangements can make a significant improvement in the effectiveness of your percussion ensemble. Arrangements written for your group are always the best option, whether by an outside arranger or by your percussion instructor. The arranger needs to know a few things from the start.

First, they should know the style of the show and the charts. They should be informed if it is a custom arrangement or a rearrangement of a stock chart.

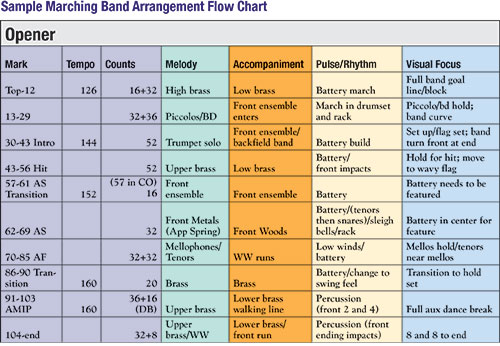

Provide a flow chart for your show. This keeps everyone on the same page, including designers and staff. It allows everyone to know phrases in the show, big picture listening and visual elements, and even tempos for the drum majors. This should be updated as the show progresses. It is also important to update the scores of the arrangements as changes are made so that staff that comes in has the latest information.

Discuss specific points in the drill where the percussion might be in odd spacing or forms. There might be parts of the show where you do not want the battery to play. If you can give a clear idea about the likely staging before starting to arrange, it can prevent rewrites.

Give specifics about the size of the group, the number of players for each battery instrument, the presence of a cymbal line, the availability of front ensemble, and the use of ethnic instruments. If there is amplification for the front ensemble, this can open up some more unusual instruments as possibilities. Identify any desired electronics and whether the necessary equipment can be obtained. Provide a video or audio record of last year’s group so they can gauge talent. Also, give the expected size of the front ensemble and let them know whether there will be percussion instructors (and if so how many) to work with students regularly.

Give the ability level of the group including their skills at rolls, flams, flam accents, paradiddles and paradiddle-diddles, and grid patterns. Decide if students can handle some odd rhythmic figures or if the arranging should be rhythmically straightforward. Tell what crash techniques the cymbal lines know and how many front ensemble members can comfortably play four mallets. The arranger will also benefit from knowing if the timpanist has good tuning abilities or at the least tuning gauges.

Many programs cannot afford a custom arrangement and will need to use a stock chart, but these can be tailored for each group. Here are a few options.

Look for places where the full battery has long periods in unison. See if one section could be removed to change the texture. Space in the arrangement is a good thing musically. Changing the mallets or sticks used can also create new textures. Try using a concert snare stick or some type of brush on the snares. Snares sticks can be an effective sound change on tenors.

Look for repeated patterns where a new sticking could heighten the students’ ability levels. Stock charts often leave out stickings, or use more basic stickings, that can be enhanced for students.

Many of these charts will be based more around orchestral rolls than open rolls. Change some to open if it makes sense musically.

Many of these charts will have limited front ensemble parts. Use a flute part on the vibes, a trombone part on the marimba, and an edited tuba part on the timpani to fill out the sound. If you have a weaker section in the winds, add that part to the front ensemble to improve the ensemble sound. It is a good idea to adjust the octave or interval that these parts lie in so they are not be in exact unison with the particular wind instrument. Many times, moving some parts up an interval of a fifth can add color and projection to the front ensemble where they would normally get lost in the wind instruments. Add more auxiliary instruments where appropriate, especially cymbals and concert bass drum for impacts, and ethnic instruments throughout.

Remove some of the unison bass drum parts – stock charts often have many. Save these for major impact points in the show. Also, adjust the parts for the number of bass drums you have. If the part is written for four and you have five, split the 4th part between your 4th and 5th drum, or save drum 5 mostly to double unisons and impacts. In a rock or jazz show use drum 5 to simulate a drum set bass drum while the other drums play the written part. This can be a cool effect. If you have fewer drums than written for, assign one player to cover two consecutive parts (i.e. player one plays 1 and 2, not 1 and 3. This would alter the pitch sequencing too much.)

Special effects in the front ensemble can increase the overall General Effect (GE) of the show. Here are a few common examples:

Suspended cymbal upside down on the timpani. Rolling on the cymbal can create an eerie, shimmering effect. Moving the pedal up and down can also glissando the pitch of the cymbal.

Bowing any instrument can be effective but metallic instruments (especially crotales and vibes) would be most effective outdoors. Ampli-fication can also make this a more effective outdoor technique.

The marching machine is a set of small wooden blocks suspended from a frame. When this is played against a piece of wood (a desk, table, or even concert bass drum shell) it can approximate the sound of marching troops.

Metallic objects that work effectively outdoors include brake drums, and empty propane and tanks. Large, thin, metallic sheets can also produce the sound of thunder.

Have as wide a variety of cymbals in the front ensemble as possible. Utilize not just suspended cymbals but splash cymbals, ice bells, sizzle cymbals (can be simulated with a chain laid across a larger cymbal), Chinese cymbals, and more. A collection of gongs and tam-tams in various sizes can add variety to the sound.

Rope-tuned snare drums can be very effective as can drums ranging from African to Brazilian to Japanese Taiko drums. These can add a great authentic sound to the arrangements.

Finally, the key to any marching percussion arrangement is the voicing. Think of the battery percussion as an STB choir. The snares are the soprano voice, the tenors are the tenor voice, and the basses are the bass voice. When writing, use this voicing as a guide to follow the wind parts. A basic set of doublings is snares with trumpets, tenors with mellophones, and bass drums with tubas. This can avoid an overly thick texture throughout the show. Remember that it can be even more musically interesting to mix and match different wind and battery timbres (basses supporting trumpets or snares as a higher timbre to tubas.)

See if you can hear the wind music in the battery scoring – particularly when they play by themselves – either melodically or as a particular rhythmic support line. If neither seems to work, make adjustments.

In addition, think of the front ensemble in the same way with the xylophone and bells as the soprano, vibraphone as the alto, marimba as the tenor, and timpani as the bass. The front ensemble should also be approached as a concert percussion ensemble in its scoring. This mindset can guide the custom arrangement or adjustments to a stock arrangement.