Daily warm-up routines that focus on tone, matching pitch, tonguing, articulations, and chorales for blend and balance are commonplace. About 10 years ago, I added range-building exercises to my daily warm-ups with my middle school band program, with spectacular results. I am a trumpet player and have middle school students who can play higher than I can.

The First Year

When I started teaching, I only used the fingering chart in the back of the method book if someone played the wrong note and I did not remember the fingering. What I failed to realize was that I am a visual learner, and some of my students might be as well. I started marking the low concert Bb on students’ fingering charts, with a goal of getting every student to play a one-octave Bb scale by the end of the first year.

My beginners are divided into woodwind and brass classes. Woodwinds meet Monday sand Wednesdays, and brasses meet Tuesdays and Thursdays. The full band meets on Fridays. Percussionists come every day because they need more time to learn everything percussionists have to learn.

On woodwind days, I sometimes take the clarinets aside to work with them down to low F. Once they can play a strong low F, I then show them the register key. I have found this to be helpful for getting clarinetists over the break.

For the first two weeks with my beginning brass students we only use mouthpieces and play call-and-response rhythms. I teach brass players two types of buzzing, called horse buzz and bumble bee buzz, terms I learned from Scott Watson, the tuba professor at the University of Kansas. Horse buzz, so named because children can relate to the sounds horses make, is a slow buzz with warm air. I have all brass players blow slow, warm air on their hands before we start playing. Bumble bee buzz is a fast buzz done with cold air and a smile. I used to tell students to firm the corners of the mouth, but this is a difficult concept for beginners, while everyone understands what a smile is.

I don’t teach students the terms at first; we start with siren sounds on the mouthpieces. I will have kids alternate the horse buzz with the bumble bee buzz. Then I demonstrate the siren on the mouthpiece going from low to high to low. Brass students love doing this, and I have fun challenges to see who has the best siren.

While working up to sirens I watch students to see whether they produce a high or low buzz at first. Students who produce a high buzz will need to relax and work on the horse buzz, while students who buzz quite low should first be brought up to a Bb and work on getting a good sound there before expanding the range.

Second Semester

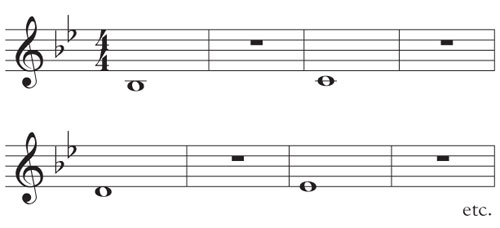

We start working on the Bb scale second semester. We open the method book to the fingering chart and play a scale, alternating between whole notes and whole rests. This break between notes gives woodwind players a chance to find the fingering for the next note and everyone time to take a full breath. By the end of the year almost all students can play the one octave scale, with the exception of some struggling clarinetists.

I have found that if a song only uses six notes, many band directors focus on those six notes so students can play that particular song. If you encourage and challenge your young students to see how high they can play, you will be amazed at what they can do. They have all the information they need from the fingering chart. Last year, I had fifth-grade flutes, clarinets, a trumpet player, and a baritone player who could play a two-octave Bb scale.

The Second Year

Several years ago, I was invited to spend a day with the Blue Devils Drum and Bugle Corps. I sat inside their warm-up circle and was forever changed as a teacher by how loud their lip slurs were and how powerful their pedal tones were. I had never heard a group whose pedal tones were as loud as their highest notes. I realized that I needed to focus on the lower register daily so that my middle school band students know the importance of consistency of sound.

We start with chromatics in sixth grade. I have students start on low Bb and descend as low as they can, still in the whole-note-whole-rest pattern. Students will run out of notes at different times; for example, a trumpet player will run out of low notes before a trombonist with an F attachment. It is worth noting that I would have an oboist start on on Bb4 and a bassoonist start on Bb2 rather than having both of these instruments start on their bottom Bbs (assuming the oboe had a low Bb key).

Then, I go immediately to the flutes alone, who start on their low F and descend by half steps down to C. I have them play this twice, as loud as they can. I explain to the flute section that in my middle school band they most likely will never see music with that low C, but it is important that they learn to play the full range of their instrument.

Next, everyone in band will play a one octave chromatic ascending scale starting on low Bb, alternating with whole rests. I will then have all students stand up and we continue the chromatic scale up a second octave. I have them stand so I can monitor how high students can play. Most of my brass players can get to the next F with little difficulty. It is in going up to the high Bb that I emphasize the bumble bee buzz and everything it takes to produce it. I also talk about the clarinets and saxophones needing to smile (firm corners) to lift their pitch around that second F. Students are instructed to sit down when they miss a note or when they reach their full range – which typically happens to alto saxophones first – but to keep fingering while sitting.

After high Bb, I will have every student who is still standing play individually and will praise each of them while providing feedback. I then revisit smiling and the cold air concept – at this point, I describe it as freezing air – for this group of high notes. We continue the same steps and we keep ascending chromatically. A handful of my 6th grade clarinets make it to altissimo G, and a few trumpet, baritone, and trombone players will attempt to go up to the equivalent concert F (G6 for trumpets, F5 for low brass). For most of my brass, I write the notes into their fingering charts At this point these brass players are playing notes higher than the fingering chart shows, so I write them in.

My sixth grade trumpets are never going to get a part from me that goes higher than E5, but I have learned that if you don’t tell students something is difficult – and can teach them how to move air and buzzing correctly, you can help students develop their range.

Conclusion

The best things about building range in younger players are that it is loud and there is safety with numbers. Students are much more likely to try to play high in a group setting than they would practicing at home by themselves. They are also less concerned about what their peers think at this age than they will be in high school. As long as the band room is a safe place for kids to fail, they will make the attempt. They will also motivate each other. If one student learns something new and shows it off, suddenly everyone else will want to learn how to do it, too. Teach them how to use their air and never tell them something is difficult, and students will grow into outstanding young musicians.