These days, most flutists realize that when playing Baroque music there is an obligation for ornamentation. In my own teaching I have all types of students with a wide span of experience and knowledge, ranging from students who wonder how to play a trill properly to those who can improvise extensive ornamentation at sight. Most are somewhere in the middle. Many clearly find the whole idea daunting, especially if they are not surrounded by well-played Baroque music on a regular basis.

One of the ways a performer was evaluated in the 18th century was by the quality of the ornamentation. For singers, this was one of the most important ways to display individual talents and taste. Instrumentalists of high caliber were expected to be able to move their audience by the beauty and inventiveness of their ornaments.

To play Baroque music well today, whether on a modern flute or a historical instrument, ornamentation is part of the language of expression in most Baroque music. Learning about ornamentation helps greatly in interpreting Baroque music as a whole.

Two Types of Ornamentation

Ornamentation is a huge topic. It means many different things depending on the country the music is from, its style, and when it was written. It is often broken into two main groups. The first group, found to some extent in all Baroque music, is the ornaments that are attached to individual notes. These are things that are notated in the music by various signs which tell players the composer’s intentions. Included in this category could be trills, appoggiatura, mordents, turns, and many other things. Quantz calls these the essential graces. As an example, the French composer Hotteterre, at the beginning of the 18th century, notated ten different signs for use in his flute music.

The other type of ornaments are what Quantz called the extempore ornaments. These are generally ornaments that hook notes together, turning a few notes written by the composer, into a group of many notes. This is often referred to as Italian ornamentation, as it was a fundamental part of the Italian musical tradition. This article will focus on the second type of ornaments.

Ornament chart from Hotteterre’s Premier Livre, 1715, Paris

How to Learn Ornamentation

My best advice is to follow the directions from the Baroque period. There are many sources that teach about learning ornamentation as well as many example pieces that show possible results. One of the best sources is Johann Joachim Quantz’s famous treatise, “On Playing the Flute,” (English translation by Edward Reilly, 1966). Quantz dedicated roughly 40 pages to teaching about ornamentation, not including cadenzas.

The most common method for learning to do melodic style of ornamentation is to create or memorize multiple ways to ornament a given interval. For instance, Quantz showed eight or more ways to ornament the most common intervals going from most simple to most complicated. This method was not invented by Quantz, as it goes back at least to the Italian diminution treatises of the 16th and 17th centuries, such as Ganassi, Dalla Casa, and Rognoni.

Another specific way to learn about extempore ornaments is by written out example pieces by various composers. These include the violin sonatas of Corelli, the Methodische Sonaten of Telemann (where the first movement is always completely ornamented), and works by various other composers. The third, very useful method, is to listen to performers of today, who have fine skills in this area.

Take a look at a couple of examples on the next page as presented by Quantz. It is important for a player to build up a vocabulary of ornaments that can be used in various situations. This is the idea that Quantz was trying to teach. It is less about memorizing his specific formulas and more about creating your own repertoire of ornamental patterns that you can use when the time is right.

Decidng Where to Put Ornaments

I find when students first are asked to think about ornamentation, it is difficult for them to do so because they have missed the first step – choosing where the music would benefit from ornamentation. When approaching a movement, one first should fully understand it and its expression without adding ornaments, other than things like obvious cadential trills. It is essential that the solo line player understand the relationship between that line and the bass. Extempore ornaments require an understanding of the harmony, which is clear when the bass is taken into account, but not when thinking of the top line as a melody all alone. Some notes on this from Quantz:

Some persons believe that they will appear learned if they crowd an Adagio with many graces, and twist them around in such fashion that all too often hardly one note among ten harmonies with the bass, and little of the principal air can be perceived. Yet in this they err greatly, and show their lack of true feeling for good taste. They pay as little attention to the rules of composition, which require not only that each dissonance must be well prepared, but also must receive its proper resolution, if it is to preserve its agreeable character; for otherwise it would become and remain a most disagreeable sound. Finally, they are ignorant that there is more art in saying much with little, that little with much. If Adagios of this sort do not please, the execution is once more to blame.

Likely places to ornament are cadential figures, leaps (especially those going up), and sequences or other repeated figures. The first step is to identify where you think the music would benefit from ornaments. Sequential figures are a basic technique of composition in Baroque music and are easy to find. Quantz suggests:

You must play the principal subject at the very beginning just as it is written. If it returns, a few notes may be added the first time, and still more the second, forming either running passage work, or passage work broken through the harmony. The third time you must again desist and add almost nothing, in order to maintain the constant attention of the listeners.

This is only a general strategy, and performers should also take into account the character of a given segment of the sequence. This is fairly simple if the line is just something moving up a step at a time, but more complicated if the statements move higher and lower.

Ornamentation is especially important in repeats of slow movements. Playing a repeat just as it was done the first time would not have been appreciated in the Baroque period.

Skips are always inviting to ornament, while a scale is not always the best choice. Skips are by their nature harmonic, so ornaments built around the chord being outlined are often more interesting than a simple scale figure. As you see in Quantz’s interval examples, he presents the associated harmony before writing any ornaments for a specific interval. Once you know the chords associated with the notes, it is quite easy to make up ornaments making use of those chord tones as well as other passing notes.

Many years ago, I was lucky to have Frans Bruggen (1934-2014) in town to do a concert and masterclass for my students. He was a noted Dutch conductor, Baroque flutist and recorder player. I remember one specific comment he made about ornamentation which I thought was particularly wonderful. “If you wish to ornament an interval going up, go first in the opposite direction – and vice versa.” For instance, if a phrase has an interval of a 4th, going up, D to G, play D down to B (a third below) and then ornament the larger interval of a 6th up to the G. This is much more interesting that simply making a scale from D to G.

I have written a short example from a brief Adagio from Handel op. 1 (see below). The top line is as he published it in the first edition. Note that he did not even bother to put in the obvious trills. Players were expected to know to do that without invitation. I then wrote two ornamented versions of my own. When working out ornamentation it is extremely useful to make more than one version. In the end you will probably end up combining ideas. The goal should be to have the creativity and freedom to do what seems beneficial in any particular performance.

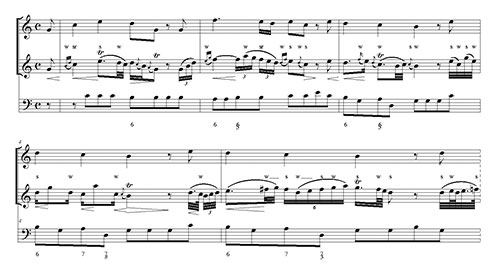

Selected Quantz Ornament Examples

More on Basic Ornamentation

One thing that feels very easy, and sometimes works, is filling in skips with scale material. This is a very basic tool that can quickly become overused. The energy of a skip going up, is usually not the same as a skip going down. Upwards usually is gaining energy where a downward skip is more often a type of relaxation. It is important for ornaments to enhance the musical idea you are trying to bring out. The rollercoaster is not a good model for ornaments. Scales can be very effective going up but less so going down, unless played in an appropriate manner. Another way to think about this is that ornaments should give the music more variation and using the same ornamental technique over and over makes the music boring.

When playing a group of ornamental notes, always articulate the note at the end of the figure. For instance, don’t slur across the bar line into the final note. This is important in helping define the basic notes which are not part of the ornament but are instead part of the original melody.

Handel, Adagio from Sonata I, Op. 1

Quantz’s Adagio

One of the most interesting examples of ornamentation and the details of musical performance in general, is the ornamented Adagio from the Quantz treatise. All flutists interested in Baroque playing should study this piece. At first glance it is a beautiful simple Adagio in which Quantz shows his composed ornamentation. How-ever, it includes much more. Quantz provided performance indications for every single note in the piece. This is extremely difficult to follow in the treatise as he gave these instructions in text, such as “In (a) E cr [meaning crescendo], G-E weak, In (b) E strong. Etc.)” rather than in musical notation.

I have transcribed the beginning of the piece translating his textual instructions into standard musical notation. I used S and W for Strong and Weak, rather than F and P as is used in many modern published versions. Quantz’s point in these notations has more to do with a relationship between the notes, rather than a literal piano and forte. One of the most important things found in his notations is that he did not want any note to sound exactly the same as an adjacent note. There is a hierarchy of importance to every note and a shape to all held notes. There has often been the thought that since Baroque composers did not write in many dynamics, the music was generally played at one volume, maybe with forte/piano echoes. Instead, as shown in the example above, the pattern was quite the opposite.

Quantz Adagio – [w=weak, s=strong, sr=stronger]

How to Perform Ornaments

This question arises once you have decided where you wish to ornament and have some ideas about what to do. This same question exists when playing pieces ornamented by the composer. A 21st century outlook usually tells players to strictly follow the rhythm as notated. This is often not what should be done in Baroque performance, and it is particularly negative in the performance of ornaments. Whether players make their own or are reading those of a composer, ornaments should sound like the performers made them up. This requires a good degree of flexibility, especially when there are four or more fast notes.

Composed ornamentation, Telemann’s Methodische Sonaten (marked cantabile)

One way to think of this is to make more of a shape than a specific rhythm. Obviously, the main notes need to fall in right places, but little notes in between can be quite free. There are many examples of ornaments where the notation does not follow the usual rules such as when there are 11 or 13 notes in an ornament that do not really add up metrically to a beat. Clearly the idea is not to try to play 11-tuplets; it is to make a nice shape with those 11 notes, starting and ending at the right time.

There are also places with a long group of 16th notes that end in a shorter group of 32nd notes. This is usually not to be taken literally but rather is just telling the player that the figure should be faster at the end. There may be exceptions to this in mid-17th century music, but it is generally true for 18th century Baroque music.

Take a look at the composed ornamentation by Telemann, from his Methodische Sonaten adove. Then as an exercise take each of Quantz’s intervals and come up with three different ways of playing each of them.

Learning to ornament is a gradual process, a combination of harmonic and melodic sensitivity, and the creative spirit. Players can create great enjoyment for the listener and for themselves, by crafting fine ornaments and performing them in a persuasive way.

.jpg)

Quantz: Basic Intervals for Ornament Practice

This article was previously published in FLUIT 2019-1 of the Dutch Flute Society (NFG). They have graciously granted permission to print it here.