.jpg)

Part 1 of this article in the March issue focused on the nature of inspiration and spontaneity, and some ways they work in our playing. It also examined obstacles and various contexts, and questioned whether these are forces flutists can manipulate and control. As mentioned previously, doing spontaneous things in concert may sometimes be inappropriate, but spontaneity should still happen on different levels in our playing. The basic question that this second article continues to explore is how to keep inspiration going in spite of obstacles, and how to become skilled at being spontaneous in performance.

Levels and Balance

Spontaneity in performance is something to achieve. You cannot just wait for it to happen accidentally, you have to generate it. It requires skill, knowledge of the music, and presence in the moment. First, you have to consider what degree of spontaneity is appropriate and wise. In performance certain things can be left to chance, but some framework must be in place. For example, think about being on vacation. Too much planning, and experiences can become mechanical, more like chores. Too little planning, and you may miss your flight. There is a balance point. A successful experience takes a certain mastery of knowledge of your environment, destination, and yourself.

Then there are those pesky elements beyond control such as lighting, temperature, intonation discrepancies, and even the audience. Creating a positive situation is a skill. Reflect for a moment that circumstances will always be changeable in a performance, so musicians should not expect that their playing should always be the same. Usually performers just have to go with the flow and relax, even though things are not happening the way they envisioned. This may prove difficult or impossible in performance, however, if one cannot control the nerves. It is a big topic, but one aspect of feeling nervous about performance is a negative state of self-doubt. Many positive experiences must occur to build up enough confidence for spontaneity to happen in the playing.

Controlled Spontaneity

Concerning the definition of spontaneous, for this article I want to add: “within a familiar and well-defined context.” There are many different styles of music, and performance occurs in varied contexts. These can range from the nearly complete freedom of creating jazz improvisation (although many jazz musicians plan quite a few things in their improvisations) to simply changing phrase emphasis in a Gaubert sonata in the spur of the moment. In Baroque music, performers may leave some ornaments to chance. In Romantic music they may leave some tempo manipulations for the moment itself. In the very exuberant passage below from the Prokofiev Sonata, 2nd movement, the tempo can either stay stable or be flexible. When you alter the tempo more, the characterization of the phrase is more exaggerated. It works either way, and you can agree with the pianist to feel it together in the moment.

Prokofiev Sonata, 2nd mvt., m. 13-20 after no. 18

Improvised?

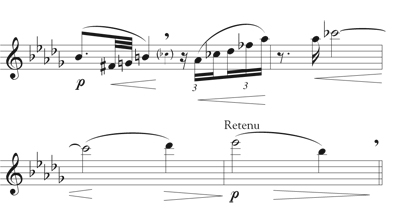

There are pieces in the repertoire, more often for solo flute, which are supposed to sound improvised, but every note is still printed. Rhythms and meters are sometimes less exactly indicated. A composer may indicate that a piece should have the character of an improvisation, such as the Ibert Piéce, Bozza Image, or some of Katherine Hoover’s solo flute works. There is space for more spontaneity, but this is not license to change everything. It means that you must conjure the attitude of spontaneity. It is easier to define this quality by what it is not. Basically, it means eliminating the characteristics of predictability in the timing and physical energy. Only certain types of pieces go that far without extending into the more extreme realm of aleatoric composition, which can have a closer resemblance to jazz improvisation.

Debussy’s Syrinx has had more than its fair share of abuse regarding spontaneity, and much has been said on the topic. Even though it is a solo flute piece I cannot think of a single reason why Syrinx should sound like a free improvisation; Syrinx is as carefully wrought as a complex algebra equation. Creating the atmosphere of immediacy and spontaneity in the performance of Syrinx is not the same as changing the rhythms and dynamics, which is an annoyingly common interpretation to this day. For example the figuration in measure 6 printed below is perhaps the most commonly bowdlerized rhythm in the piece.

Try playing the 16th note triplets in rhythm. They are often played quite fast, and arhythmically, which makes them sound like a spontaneously improvised flourish at best, or more commonly a minor onset of epilepsy. Playing them in tempo with a little crescendo, without shortening the last note, can be refreshingly poetic.

More about Re-experiencing

Spontaneity is not only a state of mastery, it is a state of mind. Earlier I said that spontaneity comes from inspiration which is a positive force; it can regenerate. The best performers are good at sounding spontaneous even when they don’t feel that way. I have heard Yo-Yo Ma play the Dvorák Concerto many times, and cannot recall a single note that was less than inspired. He did not change his interpretation every night; in fact, the basic interpretation of the piece was quite the same each performance. Similarly, Shakespearian and Broadway actors must repeat the same roles hundreds of times, but the best rarely give a stale performance. So wherein lies the spontaneity and inspiration?

The answer is that they re-experience the piece anew every time. This is very similar to telling your favorite joke to different people. You may embellish, and each time re-experience the humor as the new audience enjoys the punch line. Practice this by telling a favorite joke to several different people. I would bet that you start embellishing the story after a couple times through, and as you become more confident and familiar with the joke, your perspective on the audience changes. Maybe sometimes you laugh harder with them, or perhaps you do not laugh with them, out of a sense of confidence. Either way, you feed off of their energy, the same way performers respond to the audience’s energy as they play.

Familiarity with the material is the real key. When performers really know a work and have a genuine interpretation, they can relive the drama of the piece each time they play it. This is similar to the way a jazz artist may improvise. Though playing the same tune every night, he may choose to improvise on a certain interpretation of the harmony one performance and a different aspect the next. Sometimes inspiration strikes at just the right moment, and it is possible to play something a new way even after multiple performances, as if seeing the piece live through performance. We can develop intimate relationships with great works of music just as we can with people.

Practicing Spontaneity

Is it possible to practice spontaneity? Practice, repetition, and spontaneity, at least on the surface seem to be strange bedfellows, but looking deeper, spontaneity requires several things: flexibility, ease of execution, and the ability to think in the moment. This last quality is closely related to the idea of re-experiencing the originality and emotion of the piece while playing. Looking over these qualities, I can scarcely think of better reasons to practice.

Flexibility and ease are really the key qualities, because playing spontaneously is playing freely. So fundamentals are the place to start, and never shy away from returning to them. Practice playing things different ways and do not be afraid to experiment with every aspect. It is mainly important that you have actually heard yourself play the piece different ways. If this is unfamiliar to you, experiment with smaller examples to focus your ideas, like the excerpts in Moyse’s wonderful Tone Development Through Interpretation. Use a recorder to keep things clear. This is especially helpful with varying vibrato and rhythm.

To hone skills, isolate rhythm from other aspects. Unfortunately, when it comes to being creative, many players resort to changing the beat or using rubato, the cheapest form of musical expression. Other elements can be freely manipulated to great effect without changing the beat which can be of benefit in cases where the composer clearly does not want the tempo to be changed, such as the flute solo of the finale of Brahms’s 4th Symphony. In his book The Composer’s Advocate, conductor Erich Leinsdorf clearly expresses his disdain for slowing down the tempo for expressive means in that solo:

“In the finale of Brahms’ Fourth Symphony…a crucial tempo relation – the quarter equals the quarter at the start of the flute solo….is most notable for being disregarded…the common approach is to ritard gradually as one approaches the 32 and then let the first flute player have his arioso….Here the languid treatment by most flute players creates a 64 in which the sighs of the strings and horn fall on actual beats instead of being felt as syncopations…they lose the quality of anxiousness that Brahms intended.”

(From The Composer’s Advocate, Erich Leinsdorf, Yale University Press, 1981. pp. 147-148)

If one agrees with Leinsdorf, then it is clearly important to be able to create the expression of the solo without having to slow down the tempo. This requires flexibility with other elements of the tone such as color, dynamics, phrasing, and vibrato.

Stravinsky was also concerned about issues of rhythmic manipulation in his indications regarding the famous cadenza in Petrushka, where he clearly advises the flutist not to accelerate the tempo. The cadenza must sound spontaneous without hurrying.

3 Bars At No. 31, 1911 version, flute 1

After working on expanding your skills within certain boundaries, risk performing spontaneously for friends and family who are a less critical audience. Try a new interpretation; it may be a version only a mother could love, but at least you will get the feeling of going for different things in the piece. Experiment with aspects which you do not carefully plan.

If a piece is feeling stale, take some time away to allow the heart to grow fond again. Keep moving through new repertoire as well, but with pieces that are familiar, take a more serious look, as in the Mozart example in part 1.

Looking at things from a different point of view can also keep the door to spontaneity open. Listening to a good live performance or a famous older recording can help. Also, do some biographical research, or specific reading on the composer’s works. I was re-inspired to play Brahms’ 4th Symphony after reading The Taking Back, a chapter concerning the last movement in Jan Swafford’s biography of the composer:

“…the B section…begins with a flute solo of unforgettable tragic beauty, exquisitely poised between moll and Dur…In the Coda of the Fourth Symphony there is no transformation but rather a sustained tragic intensity that reels to the final E minor chords…Brahms does not turn to major at the end of a minor-key piece. He allows the darkness to stand, gives tragedy the last word…Brahms Fourth narrates a progression from troubling twilight to a dark night…With this work Brahms at the onset of old age shaped his apprehensions and prophesies into a vessel of consummate craft, his dark answer…to Beethoven’s (Ode to) joy."

(From Johannes Brahms, A Biography by Jan Swafford, Vintage Books, 1997, pgs. 525-526.)

Craft

The bottom line is that you must be comfortable with your skills in order to have enough free energy for spontaneity and revitalized inspiration. When the piece requires that few if any liberties can be taken, skills are even more important. In that case you can concentrate on the pleasure of recreating the work in exactly the same way, or the enjoyment of sharing music-making with friends and colleagues. On the most basic level of creativity, the craft of flute playing itself is so immeasurably complex and fun, that playing the flute can become a spontaneous expression of joy each time you pick up the instrument.