A few years ago I was privileged to perform The Enchanted Forest by Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762). This Baroque masterpiece is one that I had read about but never heard, either on a recording or in person. I was intensely curious about the music and was not disappointed. I knew that Geminiani had written one of the earliest pedagogical treatises, The Art of Playing on the Violin (1750), and that it was based on his violin lessons with Arcangelo Corelli.

Geminiani was also famous for using a wedge shape above certain notes to indicate how they should be shaped. Sure enough, when I received the flute part, there were the wedges. Some were shaped to indicate a crescendo and others to indicate a diminuendo. The composition was exciting, and as I was performing it I thought – here it is, approximately 250 years after this piece was written, and the composer is controlling how I shape a note.

Shape of the Note

Most students never think about the shape of the note they are playing. The most common problem in shaping notes is starting the tone with a slow air stream and no vibrato and then, when confident, increasing the speed of the air and adding vibrato. Many teachers refer to this as bulbing because the shape produced resembles a light bulb. A teacher whom I admire says: Walk into the room with the lights on. Don’t walk into the room and then turn on the lights.

Three Parts of a Note

Each note has three parts: a beginning or attack, the middle, and an end. The attack has an ictus or metrical accent. Engineers at the Bell Telephone Laboratory conducted an interesting experiment. Several instrumentalists were instructed to play one note. The attack or beginning of the note was edited out. When the note was played back without the attack, it was almost impossible to tell which instrument was playing. From this it seems that it is the attack that helps us identify which instrument is playing.

When practicing attacks with a tuner, it is almost impossible to avoid being slightly sharp on the attack if the conclusion of the note is to be in tune. In his book The Horn, Guenther Schuller suggests that players aim to produce a square-shaped note. I find this is the best place to start learning how to make different shaped notes.

A Square Shape

The first step in playing square-shaped notes is learning to control the air speed throughout the note. The vocal folds should be separated as if in panting. Pant for several moments and notice how your vocal folds are separated on both the inhale and exhale of air. This position is what many teachers refer to as an open throat. I prefer to avoid that term because most flutists think their throat is some place other than in the vocal folds. Instead, I prefer to say: separate your vocal folds.

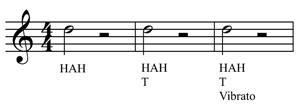

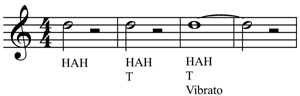

Try the following exercise:

On the first note use a breath attack hah. On the second note, while keeping the vocal folds separated as if using the hah attack, start the tone with a T. On the third note, keeping the vocal folds in the hah position, start the note with the T and add the vibrato. These three steps will help you make a perfectly square note. Repeat on several notes. Some notes are easier than others because of the tessitura or range and the response of the flute.

A Rectangle – The Middle

After making a square note, the next step is to increase the length of the square note to a rectangle. Continue to practice the above steps, only lengthen the final note by several counts.

On longer rectangular notes, the air speed is of prime importance. If the air comes too fast, the tone will bulb. If it comes too slowly, the tone will become flat in pitch. The goal is to have an even air speed. When speaking with students, I refer to this as playing with even air. Use a tuner to check whether you can keep the needle still while playing a rectangular note. Many times our eyes are better developed than our ears.

Connecting Two Notes

Once you can control playing square and rectangular-shaped notes easily, the next step is to connect two of these notes together. When notes are connected perfectly, the vibrato does not stop when moving from one note to the next but remains in constant cycling. The timbre or color of each note should be identical. This exercise is difficult and a challenge to most players, but once conquered, players can perform at a higher artistic level.

Many flutists are unaware of this on/off vibrato when performing. As mentors we must teach them what to listen for and how to fix problems when they occur. I use a voice recorder with students that records at two-times speed and plays back at one-time speed. In this teaching technique, the student plays a note or passage that is recorded at two-times speed. When the passage is played back at one times speed, the pitch of the notes is one octave lower and at half tempo or very slow. This half tempo allows us to hear the vibrato’s shape or contour, its regularity, and whether it is continuous when changing from one note to the next. The result is very much like looking at an object under a microscope. Hearing the flaws or imperfections helps students learn to listen more acutely.

The first exercise in Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite addresses this problem very well; however, it is possible to use any two notes throughout the flute’s range. Remember, the better the connections are between notes, the stronger the performance will be. Once flutists can make controlled one- and two-note connections, they should progress to controlling five-note patterns and one-octave scales.

The End of the Note

The end of a note occurs in one of two ways – either by stopping the air or by tapering or playing a diminuendo on the note ending. Joseph Mariano, the legendary Eastman School of Music flute professor, suggested that there were three ways to taper a note. The first was to slowly bring your head back away from the flute as you get softer. The problem with this method, he explained, was that it was hard to control the quality of the tone and pitch.

Another method was to slowly purse the lips. Once again he did not like the timbre of the sound that this method often produced. He thought the best way to taper a note was to purse the lips while slowly pushing the end of the flute forward. With this method, the pitch and timbre could be controlled. For the audience, there was a bonus of a visual image of the sound becoming less. Sometimes Mariano continued to move the flute forward long after the note had stopped. To the audience it seemed as if the taper went on forever.

One thing Mariano emphasized over and over again was that vibrato must stop before you go into the final tapering of the note; otherwise you have a silent vibrato cycle continuing when you are trying to end the note. Most professional flutists use a combination of one of these three methods, depending on the music at hand. Because most embouchure holes are more finely hand cut today, the results are much improved over those that were possible in Mariano’s time. Differences in under- and upper-cutting embouchure holes vary from one flute to another.

Flare

Some flutists make the poor choice of letting the end of a note flare. This happens when you dump all of the remaining air in your body at the conclusion of the note. Many folk singers do something similar. They let a rush of fast vibrato pulses out at the conclusion of a note because they relax the tension of the vocal folds before ending the note. For most musical situations that flutists encounter, this is not a good way to end a note.

Tongue

Many flutists develop the habit of ending the note with the tongue positioned too high in the mouth. A high tongue changes the timbre of a once beautiful note to something that is not so good. I believe this happens when a player anticipates using the tongue for the next attack before they have finished the note that they are currently playing. Once again, a voice recorder will quickly illustrate this problem. The solution is easy: keep your tongue in place and wait until you are finished with one note before you play the next.

Triangle Taper

I like to use a triangular shape to illustrate a taper or diminuendo. For many students, playing a triangle simplifies the process and produces better results. Triangular-shaped notes are excellent to use on dotted quarter notes. A simple acronym is: DDT -decay to the dot or tie. This small diminuendo adds interest and expression to most any melody.

All The Same?

Obviously when playing a phrase of music that includes many notes, we would be boring players if each note we played were square or rectangular shaped. To be interesting we may choose to make notes of various shapes. The final decision in choosing the shape depends upon tempo, range, note length, and style period.

Guilio Caccini first discussed the vocal technique messa di voce in his treatise Le nuove musiche (1601-1602). In this technique the performer sings a gradual crescendo and then decrescendo on a sustained note. Messa di voce later became one of the primary exercises in the bel canto style of singing and is still used in many vocal studios today.

This is also an excellent exercise for flutists to practice; however, there are few places in flute literature other than in cadenzas or preludes when it is truly appropriate to apply this technique. Unfortunately, many inexperienced players try to use this technique when playing in block woodwind chords. My best advice is to practice messa di voce because it will help you discover more facets of your tone, but keep the technique in the practice room unless you are playing a prelude or cadenza.

Other Symbols

The first sign to come into common use was the staccato (early 1700s). It could be shown by a stroke (dagger pointing down), dot , or wedge (dagger pointing sideways) to indicate an accent as well as separation. Generally today the staccato implies the note is detached from the notes on either side of it. Another early symbol was the accent > or little diminuendo. Unfortunately common usage implies the accent is played stronger or louder rather than as a little diminuendo. Experiment by playing the accent as a little diminuendo rather than hitting the note harder or stronger and staying there.

Noted flutist, Claude Monteaux, told me that his father, legendary 20th-century conductor Pierre Monteaux, instructed the members of the Boston Symphony to play the accent as if saying the word die. Notice when you say the word die there is a natural diminuendo.

Two other markings that influence the shape of notes are the tenuto and the portato markings. For most situations flutists treat these two markings similarly. Tenuto means that the note is held. Generally there is a slight separation between the two tenuto notes.

Developing Inflection

Learning to play with inflection is a life-long process. Active listening at concerts and on CDs will help you discover the variety of note shapes that you can choose from to make your music more interesting. Playing without inflection is like listening to a person speak in a monotone; playing with inflection is like listening to a great orator. In order to play with inflection you must have excellent control of the air speed. Practice with a tuner, not to check the pitch, but to keep the needle still while playing a whole note. This exercise will show if your air speed is even. Once you can play with even air, it will be easier for you to insert inflections or small diminuendos into your music. The added bonus of this type of practice is that the greater control you have over the shape of a note, the better you will play in tune.