There are certain flute lessons from my student days that I can remember almost verbatim. One of my favorite lessons to recall is one with Julius Baker from the summer of 1963. I had prepared the Bach Sonata No. 1 in B Minor. After I played the first movement, he said, “Two comments. First, I think to make it today as a flutist, you need to be able to play the Taffanel & Gaubert exercises at quarter = 144, and second, for the next lesson bring in the slow movements to the Bach Sonatas preferably memorized with four vibrato cycles to each eighth note.” Then we played duets. I loved playing duets with him trying to match every nuance and the way he turned the phrase. Baker was known for his beautiful, lush sound and exquisite technique. Joseph Mariano played a lot of Kuhlau Duos with me during my first three years of study with him at Eastman, so I knew the game. After the duets, Baker loaned me a book of Schade Etudes to learn for future lessons. After the lesson, I went back to my apartment which was just a few floors higher in the same building where I was apartment sitting for another tenant.

My plan was to take three lessons per week (M, W, F) and practice six to eight hours a day. In the evenings, I often joined the Bakers for dinner and sometimes trio reading with another student. This was great fun and I was able to meet a lot of NYC flutists. When I wasn’t practicing, I listened to the radio. Growing up in Amarillo, Texas, there was no classical radio station, so listening to WQXR was a treat. One of the most treasured parts of this programming was the live interviews. I remember one with Isaac Stern in which the interviewer asked him what set him apart for other concert violinists? Stern replied saying something like there are many violinists who have the same or better technique than I have, but I like to think I put something between the notes. This was the same concept that Mariano spoke so often about in lessons – playing between the notes. Mariano talked about notes being three dimensional in that there was the beginning of a note, the middle of the note and the end of the note. The end of the note was the beginning of the next note and so on. He also referred to two notes as being like two pieces of bread and encouraged me to fill the sandwich with more than mayonnaise.

When I returned to my apartment, I thought about my next assignment and reflected on Baker’s comment about being able to play the Taffanel & Gaubert at 144. In those days, the T & G wasn’t as popular as it was to become in the 1980s and on where teachers like myself assigned the entire book of exercises. Most teachers focused on No. 1 (Five-note pattern, major), No. 2 (Five-note patter, minor), No. 3A (Two-octave scales in modes), No. 6 (Thirds and Sixths), No. 7 (Right-hand finger twisters) and No. 12 (Seventh Chords). All of these are in simple meter except No. 6 which was played six notes to a beat at 80 bpm.

I had begun studying the T & G several years earlier with Frances Blaisdell at a summer program at Interlochen. I was familiar with how these should be executed so when I checked my playing with the metronome, I could easily play the exercises at 144. Good, one thing off my list to drill.

I have thought about Baker’s tempo suggestions through the years and about 1990 decided if a flutist was going to make it today, the metronome should be set on 160. Now I would say 200. This just shows how the technical demands of flutists have increased through the years.

Bach Slow Movements

There are nine slow movements in the six Bach flute sonatas. I got to work on Sonata No. 1, second movement Largo e dolce. This siciliano movement is one of the loveliest of the nine. I wondered why Baker had made this assignment and soon discovered that I had no control over the vibrato, and my counting was anything but accurate with the metronome.

Before I go on, I do want to share that Baker said practicing the slow movements in this way was not authentic Baroque practice, but by using these notes, my vibrato control and rhythmic subdivision would improve. And, I would know the sonatas much better. Many years later when interviewing Robert Willoughby, I asked him where he started new students, and he replied, “The Twelve Telemann Fantasias.” I inquired if this was to teach early music practice and he said, “No, just as a basis for teaching musical understanding and phrasing.” Baker was doing the same thing. As we now know, in early music vibrato was used as a coloring device and would never have been placed on each note of a slow movement.

Several years earlier, Frances Blaisdell had shared how her teacher Georges Barrere taught her vibrato. It was done in the vocal folds by playing a second octave C with a very soft breath attack, first four quarter notes, then eight eighth notes, followed by four sixteens, and the four counts of spinning the vibrato cycles. After the second octave C, I was to progress descending chromatically down to low octave G. If I could get a whistle tone on each note, this was even better. I had developed vibrato naturally, so this exercise gave me more control of the vibrato cycle. When I heard how uncoordinated my vibrato was in relationship to the note values in the Bach slow movement, I decided to practice Barrere’s throat staccatos (breath attacks), four to the eighth note until I could do the A section of the Largo e dolce. This proved to be more difficult that I had expected. However, once I could do it accurately, then it was easy to slur the breath attacks making the desired number of vibrato cycles in time with the metronome.

I memorized this movement as well as the famous Siciliano movement in Sonata No 2 for my next lesson which was two days away. When I played the two movements for Baker and apologized for not having gotten to the other seven movements, he smiled and said let’s move on to the etudes. In future lessons, he never asked for the other seven movements because I had corrected my issues with the first two slow movements.

Another benefit of this type of practice is that it improves your fingering control. To keep the vibrato continuous, the finger must move at the point where one vibrato cycle stops, and the next begins; otherwise, there will be a place where there is no vibrato at the beginning of the new note. The take away here is that to have good control of the vibrato cycle, the air stream must be separate from the fingers.

Applying the Principle of Subdivision

Subdivision can be taught from the very first lessons. With the teacher and the student using the headjoint only, the teacher plays a whole note, and the student fills in with four quarter notes, switching parts every four counts. Repeat with one playing a half note and the other two quarters. Even dotted half-notes can be taught in this fashion. Repeat this idea when introducing eighth notes too.

For intermediate and advanced level flutist filling quarter or eighth notes with sixteenths is beneficial. Take the following two octave scale filling in each note. (Fill in with 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 notes using T, K, Hah, TK/TKT or Vibrato Cycles.)

Marcel Moyse uses this filling in concept in his 24 Little Melodic Studies. Melody No. 1 is presented first in half and quarter notes, but in the Variazione, he fills in with eighth notes. In Melody No. 2, the Variazione is filled in with triplets. Moyse continues using this idea through most melodies, and even if he doesn’t, a clever teacher will have students do this.

Dotted Notes

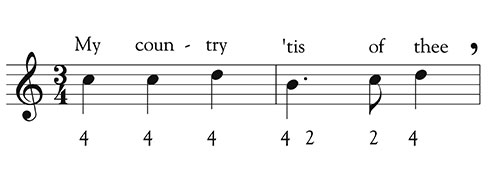

Notes with dots after them are confusing to flutists young and old alike. Most students understand theoretically that the dot after a note increases the value of the note by one half. It is the execution of this that is the problem. Let’s look at the first phrase of the song America. If filling in with four sixteenths per quarter, the dotted note receives four sixteenths for the first beat and two sixteenths for the dot. Noting the number of sixteenths above the dot helps many to better understand this concept, especially in the “’Tis of thee measure.”

(From Flute 101: Mastering the Basics by Phyllis Avidan Louke and Patricia George)

On Auditioning

When listening to auditions, it is the lack of accuracy of placing the note after the dot that hinders many. The famous Gluck Minuet and Spirit Dance often appears on audition lists. Many flutists have asked why such a simple piece would be included. Simple it is not. The audition committee is listening for accurate subdivision so spending time filling in the notes on this excerpt is well worth the effort. The lack of control of the vibrato cycle is objectionable to many audition committees. Learning to subdivide is the answer to both these problems.