The drummer in a big band or combo has a great deal of responsibility. Here are some tips for improving your drummers, and by extension, your entire jazz ensemble.

Establishing Swing Time and Feel

This is the main concern with many young groups. I have always felt that a band will sound good with a unified rhythm section, even if the wind players are less experienced. A rhythm section that plays with good time goes a long way toward helping the rest of the band sound great. When I have worked with groups where the time feel is ragged, the first thing to teach them is that less is more. I have drummers focus only on the ride cymbal, because that is the main time keeper and what will lock in with the bass and guitar.

In clinics, I often notice that the bass player, guitarist, and drummer not only cannot see each other very well, but aren’t even looking. I have the guitarist turn around and play his part with just the drummer, instructing the drummer to watch the guitarist’s strumming and the guitarist to watch the drummer hit the ride cymbal. While they are watching, they suddenly lock in. Then, I do the same thing with the bassist and drummer, and the bassist and guitarist. Once that feels good, I include the hi-hat on beats two and four because it adds the back beat. Working on this helps students focus their listening on the attacks and sounds they are creating. This goes a long way toward helping the time feel better.

Ride Cymbal Patterns

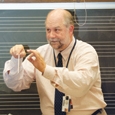

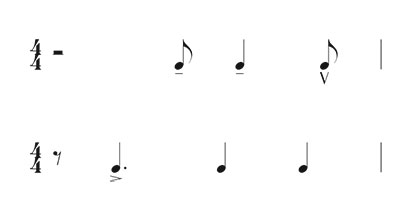

When a big band is swinging along, varying the pattern is an unwise idea, because you don’t want to confuse the written phrasing. In a more intimate setting, a good soloist will occasionally play through a phrase. In other words, the soloist may start a rhythmic pattern or harmonic sequence a bar before the end of the phrase and continue playing it through to the second or third bar of the next phrase, eliding the phrase. A quick equivalent of that for the drummer is to start a hemiola pattern of some kind and play it across the phrase with the soloist. The typical ride cymbal pattern in four is

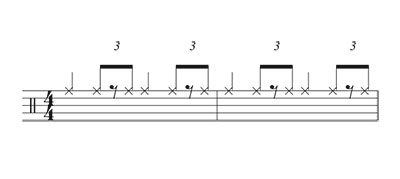

During these bars, play in three:

Every fourth set of three beats, the cycle resets. As long as the drummer knows in advance how long a pattern lasts and can plan it out so it ends at the right spot, this will work.

If there is something on beat two of the next measure, the drummer can figure out how to lead to beat two in a way that doesn’t emphasize beat one. A drummer can help mask or elide a phrase to make a more horizontal connection and create a longer idea or connect two ideas. The ride cymbal is one of the best tools for this because you can quickly change from two to three or three to two, whether at the quarter note pulse or the swing pulse.

Another way to vary the pattern is to tie across beats.

Hi-Hat Technique

There are different schools of thought about the hi-hat. Younger players gravitate toward heel down, meaning the hi-hat starts open and the toe comes down to close it. I teach students heel up. In this position, the ball of the foot rests on the pedal, and the hi-hat starts closed. Drummers use the weight of the leg to come down on the hi-hat so it produces a crisp, loud chick sound. When students try this for the first time, they immediately want to increase the distance between the two hi-hat cymbals because they need more distance for the cymbal to create the right sound. Young drummers often have these cymbals too close together.

Using Bass Drum

The drummer should support the sound of the bass player. If the bassist is playing in four, the drummer should play a felt-but-not-heard four beats with the bass drum. An inexperienced drummer can leave this out.

A common mistake I hear is that if the bassist is playing on all four beats, the drummer plays on one and three. If the bassist is in two, the drummer plays four bass drum beats. The bass drum should match what the bassist does to the extent this is possible. If the bassist plays an unusually complex bass line, have the drummer hit the bass drum on the important notes.

Use the part as a starting point if it’s accurate, and otherwise listen to the bassist and follow that player with the bass drum.

Fast Swing

There comes a point in fast swing when the swing triplet feel straightens out, and the swing feel comes more from how players accent and phrase the eighth notes. I tell young drummers to play quarter notes on the ride and not worry about the standard swing pattern. If they want to, they can insert an eighth note pattern every so often, but the priority is to avoid dragging or rushing.

Learning Patterns

When I taught jazz studies, I had a learning matrix:

.jpg)

There are only so many ways you can combine your four limbs. As an example, a basic two-part pattern would be one in which the right foot and right hand are playing quarter notes while the left foot and left hand are hitting on two and four. This matrix is a way for students to visualize a pattern and helps students who are struggling to figure out which part of the pattern is causing difficulty. You can break any pattern down and rebuild it again using the matrix.

What I’ve found when teaching a drummer a new pattern is that 80% of the time a drummer will first look at the ride cymbal pattern and play that, then keep adding the other parts until the whole pattern is learned. However, every so often, a drummer will look at the pattern and play whatever is written on the first beat. Then, they will play whatever is written on the second beat. These students look at the pattern vertically. At this point the don’t care how it sounds; they are looking to see what plays when. Gradually, they will speed it up, and suddenly there is a magical moment where drummers who learn patterns vertically switch from practicing one beat at a time to playing the full pattern correctly. When I have drummers who learn one part at a time (horizontally), I ask them to try learning it the other way. I likewise ask drummers who learn patterns vertically to try one part at a time. Getting students to look at something a different way often sheds a little light on how they are trying to learn.

Using a Metronome

Once a drummer has figured out the pattern, he should turn on a metronome to a speed he can handle and work toward consistency. As confidence grows, they can increase the speed on the metronome.

I always have my metronome next to me in the bands I play in. When a tune is called, the first thing I do is imagine what I believe the tempo will be. I then set the metronome to the given tempo marking and let it play for a couple beats to see how close my memory is. When the director counts it off, I know whether it is a little fast or a little slow and can adjust accordingly.

If a student is playing something from the Basie Straight Ahead album, have him put a metronome on the recording and figure out the original tempo. Then go to YouTube and with the metronome figure the tempo of a few other recordings of the same tune. When listening, if the tune is faster or slower, ask the student if he likes the changed tempo and why. This will give students the understanding that some tunes work across a wide range of tempos, while some only feel the best at a more specific tempo.

The other interesting thing to do with recordings is to put the metronome on at the beginning to get the tempo and again at the end to see if it remained the same. New music today is often recorded with a click track, but older jazz recordings were not. That is not to say a subtle, unplanned tempo change is right or wrong. It is possible that during an exciting solo, the feel changes, and the tempo may pick up a bit.

A metronome is meant to keep a drummer honest about how good a timekeeper he is, not to be a crutch. I like to set the metronome at half speed so it clicks on beats two and four and play any back beat style with that.

Tone Quality

I’ve been playing lately with a trio, and our performance space is so small that I am limited on what I can bring. Every time I find myself with less equipment, the more fun I have, because I can explore all the different sounds you can get out of the instrument beyond the things people expect.

Don Owens, Coordinator Emeritus of the Jazz Studies and Pedagogy Program at Northwestern University talked to drummers about how the drumset was like a whole choir and to think about his playing in that regard. He would ask drummers to play the highest sound they could, at which point, students would almost invariably hit a cymbal. Owens would then ask students to hit the cymbal in a higher-sounding place, and students would hit the bell. The aim was to get drummers thinking about what the highest sound he could actually make was, and the lowest. Hitting the rim of the highest drum is also a high sound. The cymbal is all metallic, but the rim of a drum will have a different sound. There are numerous options.

Duration is also a factor. Most young drummers are just trying to make things happen at the right time and not thinking about the phrasing implications. The result of this is a failure to consider filling the space between the sounds, because all drummers have is an attack followed by an immediate decay. However, a snare, tom, ride cymbal, and crash cymbal all decay at different rates. I have drummers think of them as wet and dry sounds. Playing a ride cymbal creates a wash of sound over the ensemble; I call that a wet sound. Comparatively, hitting a snare or a closed hi-hat is a succinct, dry attack.

Mallets make a difference. Sticks are just one of numerous options. Brushes, bundled dowel rod sticks, yarn mallets (either end), or even hands can all be valid choices. In high school, I was asked to play for a choir and had to play much softer than I was used to playing with wind instruments. A pair of bundled dowel rod sticks let me play with the force and energy and arm movement I was used to, but the volume was cut in half. I am glad that happened early on, because it made me think about the volume level I played at and taught me that there was a whole other palette of sounds I could use.

Big Band versus Combo Style

The drummer is always the style leader. The differences between big band and combo playing are best viewed as one spectrum rather than two different styles. In any given big band tune, there will be some level of either of those going on.

There are elements of both kinds of playing that will work in both situations. Sometimes a drummer can be too busy when the big band is playing. There is already a lot going on; if the drummer is too involved in all of that, that can be a problem. On the other hand, if all the drummer does is keep straight time with no phrasing or interaction during a solo, that could be equally uninteresting.

The drummer’s focus in full band passages should be on driving the ensemble. In solo sections or more interactive moments, playing should be more combo-like, where the rhythm section becomes more a part of the conversation that’s being led by the soloist.

If a tune has lyrics, everyone should learn them. Someone said this to me when I started learning standards, and this got me interested in the great singers. When I listen to the lyrics of My Funny Valentine, I play a little more sensitively because I’m thinking about those lyrics as I play.

Building a Vocabulary

There are only so many ways to play eighth notes in a 44 measure. I liken it to studying vocabulary in an English class. You learn 15-20 words per week and are expected to be able to spell and define them. Here are just a couple of extremely common rhythms in jazz charts.

Drummers have to build a toolbox of rhythms and learn how to apply them across the drums in independent ways and different musical settings. Once they feel comfortable playing common rhythms, getting them correct becomes automatic.

Dynamics

In a one-on-a-part setting like a big band or combo, knowing the extremes of how soft and loud you can play is important, because one of the drummer’s responsibilities is to be the volume leader. If a drummer is playing the same dynamic all the time it will negate what the rest of the band does. Most drummers, if you try to get them to play with dynamics, you start to hear a little bit of difference, but not much. I get them to play only quarter notes on the hi-hat as softly as they can and help them realize just how softly they can play. What usually happens is that the rest of the rhythm section follows. If they don’t, ask them to.

There are times when the drummer should punch and kick things louder, but one of my favorite things to do is play softly enough that I can hear the rhythm guitar. I play in a couple of bands with great rhythm guitarists who use acoustic, Freddie Green-style instruments. I’m almost listening to that more than the bass in terms of timing my attacks.

Chart Reading

Most drumset charts contain section figures and ensemble figures. When the drummer plays ensemble figures, it is important both to help those and to keep the time solid. With section figures, the time is almost more important than the figure. A section figure is there to show what is being played over the time. If drummers want to use it to help with the patterns they play on the snare drum, this is fine, but the time must keep going. Often, younger drummers see the section figures and overplay them, causing the ensemble to lose the groove.

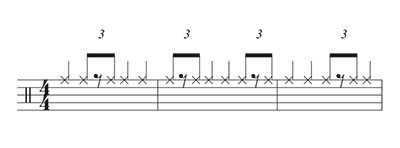

Figures written into the chart, whether they are section figures or ensemble figures, are there so the drummer knows how to lead into them for the rest of the band. It is especially noticeable when the band is playing and the horn players are hesitant to come in on a particular figure because the drummer plays it with them rather than setting it up. If this is on the drummer’s chart:

the drummer could play

or some similar lead in figure so the band feels comfortable coming in on the and of the beat. The general rule of thumb is that the longer the note you’re leading up to, the longer your lead-in can be. If you are leading into a dotted half note, then the drummer can start three beats before it. This isn’t always the best choice, but it is a general rule of thumb and tends to work.

Playing with a Soloist

When comping for a soloist, a drummer’s role is to be complementary, interact, and support. Wherever the soloist goes, the drummer’s job is to figure out how to complement it, whether by following or contrasting.

Drummers have options to spur on a soloist. Dynamically, a drummer could drop the volume to almost nothing at the beginning of a solo, either to get out of the way so the soloist starts with a clear palette or as a suggestion to start soft and gradually build. Over the solo section, the drummer could gradually increase the volume and help create a dynamic direction.

Stop time is another option. The drummer and bassist could hit on beat one and lay out entirely for two bars to let the soloist have open space.There are many options for a drummer, but you want to be careful not to overstep your bounds with the soloist. There is a great deal of give and take to this.

If a soloist is just going to play loud, high, and fast, that opens up a drummer’s opportunity to do the same. The drummer can be more rhythmic to fill the space or just play time and let the soloist show off. With every soloist there is an opportunity for creating a unique accompaniment.

Useful Resources

Advanced Techniques for the Modern Drummer by Jim Chapin.

The Art of Bop Drumming by John Riley.

Studio and Big Band Drumming by Steve Houghton.