I recently observed an honor band festival in which the guest conductor told the students to dive for their pencils. His phrasing was intended to create a sense of urgency for students to mark their music, but I was disappointed to discover how few students had pencils at the ready. Early in my musical training, I was taught that having a pencil in rehearsal was an absolute necessity. Teachers should impart this same clear expectation to students.

The importance of having a pencil in every rehearsal cannot be over-emphasized. The simple act of marking music makes an indelible imprint in a student’s mind about how the music should be performed. Teaching students to mark their music properly, greatly accelerates the total rehearsal process as it avoids wasted time spent re-visiting musical concepts that have already been covered.

At the beginning of the school year, I provide every student with a pre-sharpened pencil. This is the easiest way to jump right in, rather than waiting for every student to bring one in. During the first few weeks, I check for pencils frequently during rehearsals. Students quickly learn that having a pencil in rehearsal is required to be a competent musician. By mid-year, a fair number of pencils will disappear from folders, so I provide another as a New Year’s gift. I would rather ensure that every student has one at the ready, instead of trying to deduct points from an elaborate grading system.

I encourage musicians to keep a pencil in their instrument case. I have found, however, that the most effective way to ensure that students have a pencil ready during rehearsal is to keep them in their music folders.

Once all students are armed and ready, the real business of learning how to mark music begins. Although there are many common markings, encourage students to develop a system that makes sense to them. Students should see symbols and phrases that they can interpret immediately while playing. There is no sense in marking a part if the performer can’t remember what it means.

Here are many of the markings that students need to learn:

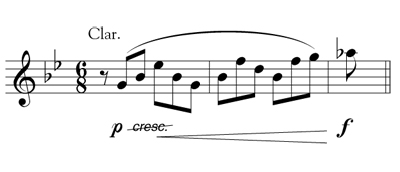

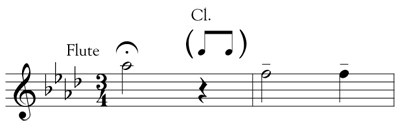

Releases: This is one of the first markings that I teach students. The two basic types are:

.jpg)

Releases are typically open-ended. This means the tongue does not stop the sound; the air either tapers softly or stops abruptly. Occasionally, the musical style requires a closed release which would be tongue-stopped like in jazz. I have students write T or aht above the release point as a reminder.

Breath Marks: Students typically breathe whenever it is convenient and not necessarily in the same place twice. Identify places to breathe early in the rehearsal process and make sure all students mark them. Similarly, teach students that they must honor breath marks that are provided by the composer. These typically indicate important phrase breaks. Students should also mark critical moments when they should not breathe. Many musicians use the abbreviation N.B. for no breath.

Phrase Markings: Students should use a solid or dotted slur marking to indicate phrase lengths. Explain the standard phrase lengths in a given piece, such as 4- or 8-bar phrases, and then students should mark any extended or truncated phrase lengths in their parts. Mark the peak of a given phrase with a star or asterisk to show where the phrase is heading.

Horizontal Arrows: I teach students to use an arrow to indicate a virtual crescendo or to maintain intensity through a given phrase. It is amazing how often students play better if they are simply reminded to use more air. Marking horizontal arrows in music is a good visual reminder.

Dynamic Changes: Composers often use block dynamics so that all instruments playing at a given moment have the same dynamic level indicated. This rarely results in appropriate balances. The most common changes needed are to correct balance issues between melody and accompaniment. Soloists should often increase their dynamics to project above the ensemble. It also is helpful to write out crescendos and decrescendos as long hairpins to show how long a given dynamic change takes to occur.

Rhythm and Meter: As students learn difficult rhythms, they should write the counting on their part or a separate sheet of paper as a worksheet. When students simply learn to play a rhythm by rote without understanding how it works, they will not remember it in the future. Have students draw vertical lines to show the beat in measures that contain highly syncopated figures or unusual combinations of rests and rhythms.

In asymmetrical meters, musicians may need to notate how the subdivisions are grouped, such as 3 + 2 in 58.

Tempo changes and transitions: Many publishers print metronomic markings on the conductor’s score but not in the individual parts. Students should mark tempos so that they know their target for home practice. If students tend to rush or drag a particular transition, it is helpful to write short phrases like: Slower than you think. Simply writing watch can be very effective too. Another common problem in transitions is when part of the band plays a pick-up note after a fermata, but the rest of the group doesn’t play until the next downbeat. Have students indicate the pick-up rhythm in their part.

Listening Relationships: As students learn a piece, it is important to identify other sections that they should listen to for rhythmic alignment, balance, or pitch center. Examples might include blend with the horns, align with xylophone, or match pitch in low winds. Instead of writing words, it might be helpful to notate the rhythm of other sections or a composite rhythm for the entire group. Early or late entrances are often the result of not understanding how one part fits with another.

Foreign Terms: Initially, I teach students that if they do not know the meaning of a given music term, they should look at the conductor while playing. This instills the importance of watching the conductor in performance. In rehearsals, provide translations for the many foreign terms that the students encounter, but simply defining a term once does not ensure retention. Insist that students write definitions directly on their parts so that they are reminded of the meaning each time they read them.

Articulations: Depending upon the publisher and the composer, there may not be enough articulations present to assist the musician with stylistic decisions. While some amount of repetition and drill is necessary to ingrain a given style, adding articulations to their parts will help musicians recall the correct style faster from rehearsal to rehearsal. For younger musicians, it is helpful to include the correct syllable as well, such as du or toe.

Mute Changes: Publishers typically indicate mute changes in music at the exact moment when a mute is needed. Students should mark the mute change at the beginning of multi-measure rests so that they have adequate time to insert the mute. In some instances, students should make a note at the top of their music to put the mute upside down in their laps before the song begins.

Fingerings: Younger students sometimes will ignore an accidental if they do not know the correct fingering. It is important to identify these mistakes in rehearsal and have students write in the fingerings. This is especially important when teaching alternate fingerings or woodwind shadings as students will forget them since they already know the basic fingering for a given note. Clarinetists should develop the habit of marking L and R for specific finger combinations. Percussionists should write in stickings for various rhythms.

Pitch Tendencies: When fixing troublesome intonation, students can use a vertical arrow pointing up or down to remind them which direction to adjust the pitch. Advanced musicians that understand the tendencies of each interval can simply mark which chord tone they have, such as M3.

Courtesy Accidentals: Students often forget to carry an accidental through the full measure, particularly when the accidental occurs at the very beginning of the measure, and the note appears again, unmarked, at the end of the measure. Students should write courtesy accidentals as needed in front of notes and large enough so that they can quickly interpret the marking. Writing an accidental above a given note is okay if there is not enough space preceding it, but don’t allow students to write accidentals beneath or after the note affected. If students miss an accidental in the key signature, they should mark it so that they don’t miss it again.

Header: It is often useful to add a header at the top of the music. For example, students might write a reminder to be patient when transitioning from an uptempo fanfare to a slower ballad.

Home Practice: Rather than take precious rehearsal time to help students practice collectively, I ask them to circle difficult passages to practice on their own. Mallory Thompson, Director of Bands at Northwestern University, tells her students that practice is when you learn your individual part, and rehearsal is where you learn everyone else’s part. Section leaders should keep a separate sheet of paper in their folder to mark down trouble spots that need to be addressed in sectionals later.

Errata: In my experience, there are very few compositions in which every music part contains the same information as the score. Even critical editions often contain errors. Students should ask questions if they believe an error might exist in a part. Once identified, be sure to mark it both on the individual music part and in the conductor’s score for future performances. Many errata lists exist for well-known compositions and can be found easily online through a search engine.

Resource Sheet: The broader concepts that students learn through the study of a particular piece will apply to many future pieces as well. While most information should be marked on each individual music part, other concepts and definitions should be recorded on a separate piece of paper that remains in the folder throughout the year. I provide students with a resource sheet, which is simply a two-sided, lined piece of paper.

This does not cover every possible marking that students might make. I encourage younger students to mark their music a great deal and then allow more advanced students to use their own judgment as to how much they want to mark.

As the students learn the music, I encourage them to memorize it. This allows them to focus more on hearing than seeing. They also spend more time communicating with one another and the conductor instead of staring at the music. If parts have been adequately marked from the beginning, then the pertinent information is permanently embedded in their memory.

After the final performance, I ask students to erase the parts before passing them in. There is nothing worse than receiving new music that is already covered in markings. It is critical that all students have the opportunity to mark the music themselves. Effective markings will remind students of important musical moments and ensure a strong performance.