Victor Herbert’s (1859-1924) earliest musical studies began on flute and piccolo. He described his initial experience in a 1902 interview, “My first effort was upon a tin flute. When I mastered the “Last Rose of Summer” I was the proudest youngster on earth, but not so my parents. I nearly drove them to distraction, and they threatened to expel me from home unless I laid aside my beloved flute.”1 As a secondary school student in Germany, he was asked to fill a piccolo position in the school orchestra. One of his first piccolo performances was the solo in the Overture to Donizetti’s Daughter of the Regiment. In an interview years later, Herbert recalled, “I do not claim that I was a piccolo virtuoso by any means. But I do insist that any player might have had the same trouble with that spot that I did. Any experienced player might have messed the thing just as I did. Besides, I had a sudden attack of dizziness when I got to it.”2 Herbert eventually focused his musical studies on the cello and was widely recognized as a virtuoso who soloed with leading orchestras of his time.

.jpg)

Popular composer Victor Herbert, best known for his songs and operettas, also wrote numerous orchestral works including, L’Encore, a duet for flute and clarinet with orchestra. A 1910 Library of Congress bibliographic card entry for an autographed score of L’Encore notes Paul Henneberg, Pittsburgh Symphony principal flutist from 1898-1904 as a dedicatee. A question mark is listed for the clarinet dedicatee, possibly due to illegible handwriting on the score, according to the Library of Congress Music Division. The score’s current location is unknown.

The composition’s date is usually designated as the publication date of 1910 or as c.1910. One biographical source notes that the duet was composed during Herbert’s tenure as conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony from 1898-1904;3 however, a search of historical newspapers and the symphony’s archives failed to turn up a documented performance of L’Encore during that time frame. Herbert also formed his own ensemble, Victor Herbert and His Orchestra around 1902, and it toured the U.S. and performed regular concerts in New York City. Many of the Pittsburgh Symphony’s members toured with Herbert and his orchestra during the spring and summer months, performing programs of lighter classical music, including Herbert’s compositions, and numerous encores.

The duet’s title implies use as an encore, but an October 10, 1909 notice in the N.Y. Times includes L’Encore on a concert program as follows:

“Victor Herbert and His Orchestra, at their second concert at the New York Theatre tonight, will present a programme in which a variety of soloists will participate. Their employment will be due to the list of selections for the first half of the concert, which comprises four numbers of considerable length, the principal being a ballet fantaisie, divided into six movements, one of these an andante for solo violin, another a “variation” for piccolo. The composition is by Flegier and is new to this country. The first part of the programme will also include Ries’s Moto Perpetuo to be played by all the first violins, Godard’s Brasilienne, and Filigran by Lackenbacher. An overture Un Jour de Fete by Ronald, and L’Encore, a composition by Mr. Herbert for flute and clarinet, will complete the first half of the concert.”

Victor Herbert and His Orchestra’s recording of L’Encore was released as Edison Standard Record 10413. The July 1910 edition of The Edison Phonograph Monthly announcing the September release reads, “A fascinating and brilliant instrumental duet written by Victor Herbert for flute and clarinet. The air is sprightly and engaging and the difficult instrumental plays are marvelously well executed. A Record of this kind is so seldom listed that it cannot fail to attract a lot of attention and consequently heavy demand.”

The Edison recording is an invaluable primary resource for tempo and stylistic information. An mp3 file of the recording is available online courtesy of the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project, Donald C. Davidson Library, University of Southern California. More information about the project is located at http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/. A search by keywords “Victor Herbert” returns a list with hyperlinks of the available Herbert recordings. Commercial recordings of the composition are also available. M. Whitmark & Sons published L’Encore in 1910 including a piano reduction. The work is now part of the Edwin F. Kalmus & Co., Inc. catalog.

This light hearted and spirited piece is well-suited for a pops or summer concert, and the intermediate level solo parts and simple orchestral accompaniment make it suitable for student ensembles and community orchestras. L’Encore would fit nicely on a program featuring American composers or as a quick encore following a clarinet and flute duet. The availability of the piano reduction also allows the piece to be considered for an entertaining encore on a joint flute and clarinet recital.

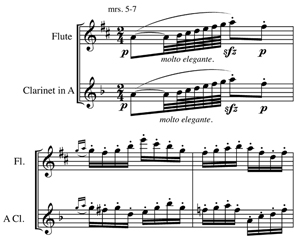

There are numerous technical and musical details to observe to ensure an effective performance of this two-minute duet. It is a mere 74 measures long, but several pitfalls arise along the way, not the least of which is intonation. After a four measure orchestral introduction, the flute and clarinet parts enter in unison from measures 5-34. The first three measures of the flute and clarinet parts are repeated four times throughout the composition.

Play the dynamics consistently starting at piano, followed by a crescendo to the sforzando and an immediate return to piano on beat one of the next measure. The 64ths and subsequent eighth notes in measure 5 should not rush. The section is marked molto elegante and should sound light and effortless. The staccato 16th notes in measures 6 and 7 should be light but not too short; you want to avoid a choppy, clipped feeling.

Subtle tempo changes add interest to this simple work, especially the poco accelerando at measures 6, 10, 27, and 31, which should keep the musical line moving forward, but not be a drastic tempo change. The sudden dynamic change to pianissimo in measures 15-16 provides an echo effect. Coordinate breathing with the clarinetist between measures 13-25 to maintain the flow of the music and keep the solo lines in sync.

The grace notes in both solo parts in measures 19-22 (see above) occur off the beat, and in the lower register in measures 20-21, increasing the difficulty in coordinating these embellishments. Use trill fingerings to execute the grace notes with more ease and precision.

The A-major section marked brillante between measures 35-42 is an opportunity to display technical skill in a playful interchange between flute and clarinet. Each part plays separately for one measure as if to say, “I can do it better than you can.” The parts come back together at measure 43 as they conclude the virtuosic section with a chromatic scale in thirds.

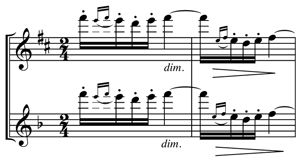

Including chromatic scale practice will help you prepare for the two-octave descending scale in measure 41, and the ascending two-octave scale in measure 45. Watch the pitch on the high A at measure 41, and B3 at the double forte in measure 43. Make a dramatic change to the piano marked in measure 45 and observe the cresendo without making a ritard into the sforzando at measure 46. There is a fermata marked over the eighth rest at the end of measure 46 in the piano conductor’s score, but it is not in the solo parts. Add the fermata and pause briefly before moving onto the next section.

The next 8 bars return to D major and the molto elegante we first heard in the opening section. Beginning in measure 65 there is a written-out trill for both soloists that is the final unison challenge. Practice the trill slowly, both separately and together, to ensure even, controlled fingers and a tight ensemble. Listen for intonation and maintain the molto elegante mood to the end of the piece. The accompaniment has the melody in measures 67-70 so back off of the dynamics and allow it to be more prominent as the duet comes to a close.

As L’Encore approaches the 100th anniversary of its publication, enjoy this nostalgic trifle by one of America’s most beloved composers as you add a touch of turn-of-the-century charm to your next recital.

Special thanks to the following for their assistance:

Kevin LaVine, Senior Music Specialist, Library of Congress, Music Division.

Nicole Philipp, Director of Media Relations, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

Bibliography

The Bulletin, Weekly Journal for the Home, Feb. 10, 1900, Vol XL, No. 16.

The Bulletin, Weekly Journal for the Home, August 31, 1901, Vol XLIII, No. 19.

Edison Phonograph Monthly (v. 8, 1910). Exact Reproduction by Wendell Moore, First Edition, 1983.

Gould, Neil. Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life. Fordham University Press, 2008.

Kaye, Joseph. Victor Herbert: The Biography of America’s Greatest Composers of Romantic Music. New York; G. Howard Watt.1931.

Waters, Edward N. Victor Herbert: A Life in Music. New York: Macmillan. 1955. Reprinted by Da Capo Press. 1978.

Footnotes

1 “Victor Herbert’s Early Efforts.” Sun, May 23, 1902.

2 Gould, Neil. Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life. Fordham University Press, 2008. pg.9.

3 Waters, Edward N. Victor Herbert: A Life in Music. New York: Macmillan. 1955. Reprinted by Da Capo Press. 1978. pg. 582.