A recent survey of 700 band directors from all levels of expertise revealed that 65% of band directors experience problems with pain in their shoulders.1 Of those who experience pain, 74% feel this pain while they conduct or directly thereafter. This is in stark contrast to the fact that only around 24% of adults experience shoulder pain as a whole.2 There appears to be at least some correlation between conducting and shoulder pain. Although conducting may not initiate the pain, it can exacerbate existing pain, keeping the shoulder from properly healing. This being the case, it is important for conductors to prepare their bodies to handle the work necessary to be successful and healthy on and off the podium.

Before going into detail on how to promote good shoulder health, it is necessary to make sure conducting technique supports good shoulder health. Below is a checklist to help assess if your conducting technique might be contributing to your shoulder pain.

1. The right hand should hold and support the baton without gripping or squeezing too tightly.

2. The wrist should move up and down, side to side, and in clockwise and counterclockwise circles freely without feeling torque or excess tension anywhere in the arm or hand.

3. The tip of the baton should lead the movement and use the most space. If after video recording yourself you see that the tip moves less than the arm, you are initiating your movement in the arm instead of the baton.

4. When conducting, you should not feel excess tension in the muscles in your arm and upper body. Let go of that impulse and trust your body to move without that excess tension, movement, and work.

5. The beat pattern is primarily at the tip of the baton, not in the joints of the arm. You will overuse your arm if it is overly invested in making the pattern.

6. Keep your conducting plane close to the middle of your torso, generally around navel height. The higher the plane, the more it can hurt your shoulders.

7. Trust your ensemble. How much do you feel you need to show your players in order for them to be successful? Do you find yourself overworked after a rehearsal or performance? If so, you may be doing the work for them instead of guiding them through their work. It is the players’ responsibility to maintain the beat and play at a steady tempo.

If this checklist reveals technical problems, work to improve technique while seeking additional methods to alleviate shoulder pain. Even if you do not currently experience pain, addressing these areas could keep you from experiencing pain in the future.

Although improving overall conducting technique can help alleviate shoulder pain, it may not eliminate all existing pain. If you are experiencing significant shoulder pain it is best to see a doctor or physical/occupational therapist as soon as you can to help create a strategy to improve your shoulder. You can certainly try the stretches and exercises detailed in this article now, but if you feel it is exacerbating your pain, stop immediately and see a doctor. The pain will only get worse if nothing is done to improve it. Once you have a strategy in place and experience better shoulder mobility and reduced pain, try these stretches and exercises to promote the continued good health of your shoulder.

If you experience only mild to no pain or discomfort, you can try these now and make them a regular part of your physical warmup. It is important to note that these exercises are not solely for those who are experiencing pain; they help promote shoulder health in all conductors and thus can help strengthen and stretch shoulders to keep pain at bay. If you feel perfectly healthy, these stretches and exercises will help you maintain that state of healthiness.

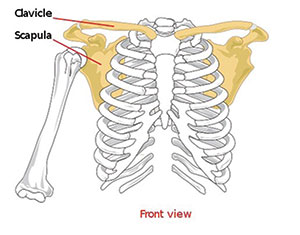

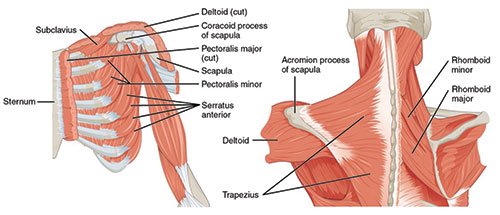

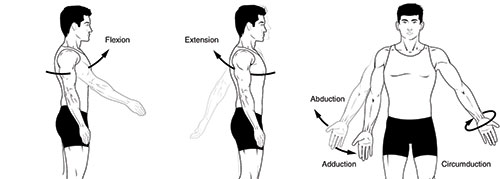

These particular stretches and exercises focus on the full shoulder (or pectoral) girdle and use specific shoulder movements common in conducting (see previous page and above for diagrams). Using varied shoulder movements, including all the muscles that support shoulder movement, creates balance necessary for good shoulder support. These stretches and exercises are not the only ones you can do; however, when done together, they support the entire shoulder girdle.

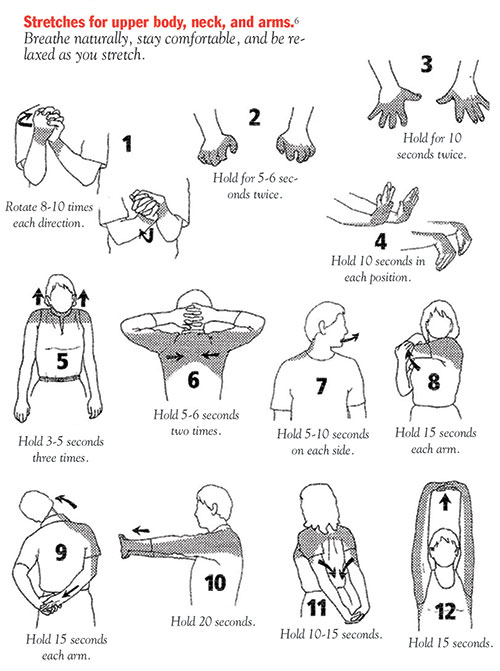

Shoulder Stretches

The twelve figures to the right are a series of stretches for the upper body, neck, and arms. These are a great starting point to alleviating stress caused by repetitive upper body movement. Do these in the morning and at night.

The following more intensive stretches also support the muscles involved in conducting movement.7 It is best to begin these stretches only if it is comfortable for you to complete the twelve stretches on the previous page.

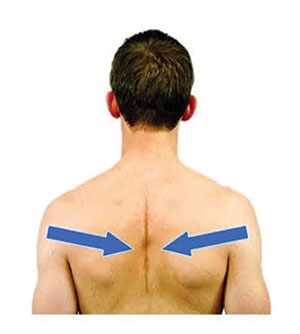

Scapular Retractions. Draw the shoulder blades back and down, holding for one second each time. Repeat ten times.

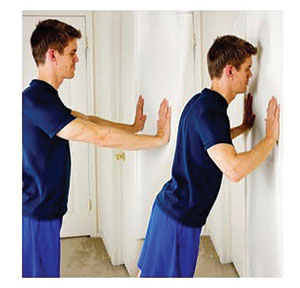

Wall Push-Ups. Place your arms out in front of you with the elbows straight, and stand so that your hands just reach a wall. Bend the elbows slowly to bring the chest closer to the wall. Keep feet planted on the ground the entire time. Repeat ten times, holding the position with the chest closest to the wall for one second each time.

Serratus Wall Slide. Place your forearms and hands along a wall, pointing toward the ceiling, with the upper arm roughly parallel to the floor. Move the shoulder blades away from the spine and then slide the arms up the wall. Hold for one second, then return to the original position. Repeat ten times.

Prone W. Lying face down with the elbows bend and palms facing down, slowly raise the arms toward the ceiling while squeezing the shoulder blades downward and toward the spine. Repeat five times, holding for one second each time.

Pectoral Stretch with Arm Raised at 90°. Stand at a corner or doorway. Place the front of the shoulder and entire arm onto the wall. Slowly turn your body away from the wall until you feel a gentle stretch in the front of the shoulder and chest. Repeat ten times, holding for five seconds each time.

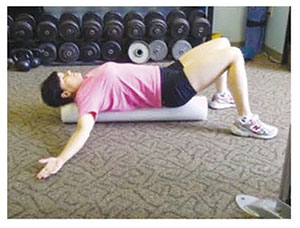

Supine Pectoralis Stretch (Snow Angels). Lie on your back with a foam roller or stack of pillows aligned under the spine. Point your arms at a 90-degree angle to your torso and let them lower to the floor, if possible. Hold this position for 30 seconds before bringing the arms above the head, while keeping them touching the floor. Hold this position for another 30 seconds, then return the arms to the original 90-degree angle. Do this exercise in two sets of five repeats each, with a short break in between.

Principles for Weight Training

When starting any weight training program, keep the following steps in mind to prevent injuries.8

• Follow a pre-exercise stretching routine, such as the one previously diagrammed.

• Do warm-up sets for each weight exercise.

• Avoid overload and maximum lifts.

• Do not work through pain in the shoulder joint.

• Stretch as cool-down at end of exercise.

• Avoid excessive frequency; get adequate rest and recovery between sessions.

• Never do exercises with a barbell or dumbbell behind the head and neck. For shoulder safety when working with weights, you must always be able to see your hands if you are looking straight ahead.

The best way to strengthen the body is through progressive resistance exercise. Here are principles of progressive resistance exercise (PRE) to follow.8

• To build muscle strength and size, the amount of resistance used must be gradually increased.

• The exercises should be specific to the target muscles.

• The amount of resistance should be measurable and gradually increased over a longer period of time.

• To avoid excess overload and injury, the weight or resistance must be gradually increased in increments of 5-10%.

• Resistance can be increased gradually every 10-14 days when following a regular and consistent program.

• Adequate rest and muscle recovery between workouts is necessary to maximize the benefit of the exercise.

• Use common sense. If the PRE principle is followed too strictly, the weights potentially will go higher and higher. At a certain point, the joints and muscles will become overloaded and injury will occur. This eventuality can be avoided by refraining from using excessive weight during strength training.

Getting Started

At the end of this section is a series of seven exercises that strengthen muscles involved in movement specific to conducting.7

• Start with three sets of 15-20 repetitions. Training with high-repetition sets ensures that the weights that you are using are not too heavy.

• To avoid injury, performing any weight training exercise to the point of muscle failure is not recommended. Muscle failure occurs when the muscle is no longer able to provide the energy necessary to contract and move the joint(s) involved in a particular weight training exercise. Joint, muscle, and tendon injuries are more likely to occur during muscle failure.

• Build up resistance and repetitions gradually.

• Perform exercises slowly, avoiding quick direction change.

• Work on strength building two to three times per week.

• Be consistent and regular with the exercise schedule.

Shoulder Flexion. Start with your arms down by your side. While holding a free weight with your palm facing your side and your elbows straight, raise one arm forward until it is parallel to the floor, then return to the starting position. Repeat ten times for each arm. This exercise can also be performed with both arms at once.

Bilateral Scaption. Hold a free weight in each hand, then raise them both up and away from your sides. The elbows should remain straight, and the movement should occur in the plane of the shoulder blades (no more than about 45° to the side). Do not shrug the shoulders. Repeat ten times.

Chest Press. Lie on your back with your elbows bent. Slowly raise the arms while straightening the elbows. Repeat ten times.

.jpg)

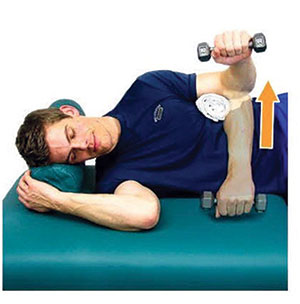

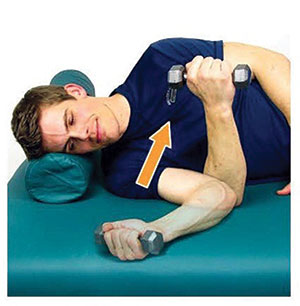

External Rotation. Lie on your side and with the arm on top, hold a weight while the elbow is bent at 90 degrees and rested on your side. While keeping the elbow bent, draw up the arm toward the ceiling. Repeat ten times, then switch sides and do ten with the other arm.

Internal Rotation. Lie on your side and with the arm on the bottom, hold a weight while the elbow is bent at 90 degrees and rested on your side. While keeping the elbow bent, draw up the arm toward the ceiling. Repeat ten times, then switch sides and do ten with the other arm. This exercise might be easier of you are rolled slightly toward your back; this takes pressure off of the shoulder.

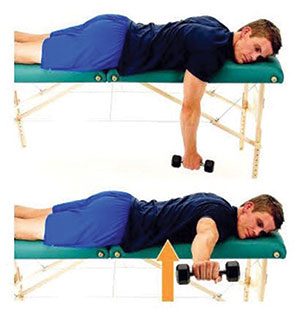

Shoulder Abduction/Scapular Retraction. Lie face down with an arm dangling toward the floor and the elbow straight. Retract the scapula toward the spine and downward. Slowly raise the arm, keeping the elbow straight. The palm should be facing down as the arm raises. Repeat ten times per side.

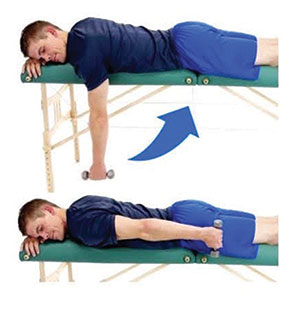

Prone Extension. Lying face down with arms dangling and elbows straight, slowly raise the arms toward the hips while keeping the elbows close to the body. Repeat ten times per arm.

Conclusion

These stretches and strengthening exercises are not the only exercises one can do to promote good shoulder health; however, when done consistently in conjunction with sound conducting technique, they can fend off shoulder injuries and are beneficial for anyone. Everyone knows the important of warmups for instrumentalists, and a director would be foolish to start a rehearsal without making sure students are properly warmed up. Nonetheless, it is easy to forget how important a physical warmup is to a conductor’s body. Take a few minutes before the day’s first rehearsal to at least stretch. After rehearsals are done, stretch again. Making a little time for this every day can keep the shoulder doctor away.

References

1 An informal poll here of band directors and shoulder pain. Could you answer below according to your experience? (Facebook status posted on June 28, 2018 by C. Snyder in Band Directors closed group). Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/

2 Shoulder Pain by R.J. Murphy and A.J. Carr (published online at BMJ Clinical Evidence, July 22, 2010).

3 Public domain illustration by LadyofHats (Mariana Ruiz Villarreal). Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/

4 Anatomy and Physiology. (Rice University, OpenStax College). Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/

5 https://www.fitnessforyou.co/

6 Hands, Arms & Shoulder Stretches (Mindful Wellness Massage and Bodywork). Retrieved from https://www.mindfulwellnessmassageandbodyw

7 Exercise and stretches compiled by Christine Philip, OT/L (Home Exercise Program, HEP2go, Inc.). Retrieved from www.hep2go.com.

8 Strength Training for the Shoulder (Massachusetts General Hospital. Retrieved from https://www.massgeneral.org/