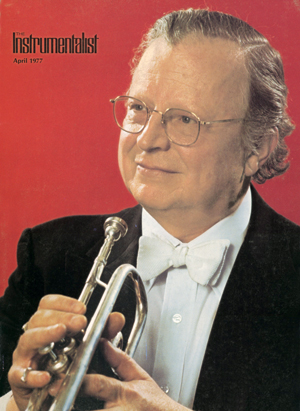

Bud Herseth, legendary principal trumpet of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for 53 years, died at age 91 on April 13, 2013. During Herseth’s tenure with orchestra, the Chicago brass sound became renowned throughout the world. As a tribute to his inspirational career, we reprint this 1989 conversation with Herseth, Arnold Jacobs, and Philip Farkas. Herseth joined the symphony in 1948 and held the principal trumpet position longer than any other player in a major orchestra. Jacobs, one of the world’s greatest brass teachers, played tuba in the orchestra from 1944 until 1989. Philip Farkas was a member of the symphony in 1936-41 and 1946-1960.

Bud Herseth, legendary principal trumpet of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for 53 years, died at age 91 on April 13, 2013. During Herseth’s tenure with orchestra, the Chicago brass sound became renowned throughout the world. As a tribute to his inspirational career, we reprint this 1989 conversation with Herseth, Arnold Jacobs, and Philip Farkas. Herseth joined the symphony in 1948 and held the principal trumpet position longer than any other player in a major orchestra. Jacobs, one of the world’s greatest brass teachers, played tuba in the orchestra from 1944 until 1989. Philip Farkas was a member of the symphony in 1936-41 and 1946-1960.

How did the Chicago Brass sound begin?

Philip Farkas: I was here in 1936, and I assure you there was no Chicago sound then. The orchestra was a motley assortment of good players. I remember being told I would play all the horn solos including the second and third horn solos; the first horn parts probably still have the solos pasted in. The trombones were a mixed bag. We were not the most homogeneous brass section; we were just capable of playing a decent symphony concert without any problems. I don’t think it was until Bud Herseth and Arnold Jacobs joined the symphony that we had a Chicago sound.

Even though I left in 1960, I was aware that we had achieved a consolidated sound and that it was a great sound. I would hear other orchestras and say, “Why do they blare?” or, “Why are they so weak?” That was never the case with Reiner. When Reiner wanted it big, you’d give it to him, but he often cautioned us not to play too big. He used to say, “I visualize the orchestra under a bubble,” and “I just heard one of the trumpet players burst the bubble; that sound went right out through the bubble and spoiled the picture; don’t burst the bubble!” That was the only cautionary remark he ever made to the brass. He would occasionally say the trombones were dragging, but every conductor says that to every trombone section.

Little by little it got to be a sound that was unique. I attribute it to the two newcomers; then we had a brass section with the soundest foundation in the tuba and the greatest soprano in the world in the first trumpet. It was as though you were on a foggy highway and had a white line down the left side, the tuba, and a white line down the right side, the trumpet. Those of us in the middle fit in naturally. It was impossible not to fit in when you had both ends so solidly grounded. The rest of us filled in the middle part of the chords almost automatically. How could I go wrong with these two men on both ends; how could I play out of tune?

You would have to be tone deaf to be out of tune with these two men guiding you. The middle of the orchestra got better because of the two ends. Not only that but as the section improved, better people were eager to join the orchestra. Every time there was a replacement, we got a better player than the one he was replacing, to the point where I don’t think there was a brass section like it.

Arnold Jacobs: There’s more to it than that, Phil. I used to sit behind Farkas, and it was such a joy. When Bud and Phil play an aria, it’s like hearing a great singer. We are in a musical organization; we all love music and we listen to great music around us. You can’t play with indifference and medocrity when you love music and you hear it all around you and have a group of colleagues who are intense, sophisticated musicians.

I remember that when I was with the Pittsburgh Symphony and Fritz Reiner, we had a good brass section. Reiner didn’t have bad brass sections; with Fritz Reiner they didn’t survive. That was part of survival: don’t make any mistakes, don’t hit any clinkers. We hosted the Chicago Symphony for one concert. They played the Tannhauser Overture and it was a fine concert. Their brasses weren’t as good as in more recent years: it was a great section up to a point, but their trumpets were a little on the weak side. The next day Reiner beat us on the head, wanting us to play like the trombones of the Chicago Symphony. He gave a lecture on how to sound, using the Chicago Symphony performance as a criterion.

When I joined the Chicago orchestra in 1944, the trombone section was excellent, and the French horn section was good. There was no unified sound, but the music was being played without disasters. The trumpets at that time were in trouble; you couldn’t play a concert without something happening — little mishaps. It was that way until they brought Bud in.

Bud joined us at Ravinia, and the first thing he played with us was Ein Heldenleben. Reiner had been my conductor at the Curtis Institute of Music for seven years and five years in the Pittsburgh Symphony, so when he came here, I knew him quite well. He came up after the rehearsal of Ein Heldenleben and said to me, “Where did you find that jewel?” I knew he studied in Boston, but that was about all.

Bud embarrasses you because he never does anything wrong. I once started to note when there was a mishap of any kind; it was about once every three years: perfection all the time; nothing ever happened. When you talk about the Chicago sound, you’re talking about group excellence, but you’re also talking about our soloists. They set the patterns and the rest of us go along with that.

Herseth: That sound was there for a long time before any of us were in the orchestra. They had some good players in this orchestra over the years, and it’s not only a matter of individual concepts of playing but an overall concept that has grown over the years.

Farkas: Bud, I have to disagree with you. That sound that’s so famous wasn’t always there; it was spotty. Yes, there were some great players then, but there were some people who were so unqualified that they took the average down.

Herseth: You’re leading me right up to my next point, which is that a good sound in any section or any orchestra depends on everybody holding up his end. One person can spoil it.

Does the choice of equipment affect the sound?

Jacobs: I think the individuals and their conceptual thoughts are the prime aspect of the sound. We used the equipment to get the sounds we wanted. Of course, it’s a different balance than you might find in the Vienna Philharmonic. They have fine brass, but I think ours met more criteria. I think there was more versatility in the Chicago Symphony that in most orchestras.

If we played French music, we’d move in the direction of French conceptions and sounds. Bud would change, sometimes I would change, and musical ideas would change among the individuals. If we moved to the Russian school or the Germanic school, there was always a change in interpretation from the members of the orchestra. We were challenged by conductors from various parts of Europe, and we did what they asked. We weren’t locked into one style.

Farkas: Everyone plays something different, yet we sound like a section. To get an even tone, you have to have different instruments.

Herseth: What you hear is the player’s concept. If I were to play a passage on a Bb trumpet and the same passage on a C trumpet, you might hear a little difference at first, but the longer I played, the more it would sound like me, not that instrument. It’s the matter of adjusting the player’s concept rather than the equipment. I remember when Kubelik first came to Chicago, he was upset that the bassoons weren’t the same color.

Farkas: The CDs have come out on the Reiner recordings; during the time I was in Chicago, I played three different horns. I listen and unless I see what date the recordings were made, it sounds like me.

Herseth: We tape all the time now. I look on that as a chance to occasionally try a different combination of trumpet and mouthpiece. Very often I say, “I don’t have to write that down, I’ll remember it.” When it comes out six months later, I can’t tell. That’s basically what I’m trying to figure out. It’s an object lesson for me. Even now when I write it down I’ll sometimes say, “I used this horn and that mouthpiece on a particular piece because I wanted a certain effect.” Certain equipment will sometimes make it easier to cope with a passage. When I listen to the tapes it all just sounds the same. Doc Severinsen said the same thing: “You don’t hear the horn, you hear the player.”

Jacobs: I think the equipment enables you to express yourself, but the ideas come from the player. I have a whole bag of mouthpieces. There are three variables in tone production: the player, the mouthpiece, and the instrument. Bud frequently would walk up with three trumpets. Occasionally, I would walk up the stairs at the hall with two tubas, but usually with one tuba and different mouthpieces. If we were playing something light, I’d use the adjustable cup, a shallow bowl-shaped cup that would suppress the fundamental tuba sound and emphasize the overtones. If you analyzed it, you’d find much stronger overtones and much weaker fundamentals. For a light effect, Berlioz and things like that, I had the choice of changing the tuba or changing the mouthpiece. Well, it’s cheaper to have one tuba and many mouthpieces than one mouthpiece and many tubas.

Bud would change frequently, according to his interpretation. He would come up with three horns, and he’d see me with many mouthpieces; we joked about it because if I ever felt I was getting bored, I would change equipment to wake me up.

Farkas: Why did this basically Germanic orchestra have the ability to play French music or Russian music? One reason is that we had many guest conductors. We had Italians, Englishmen every year who demanded certain things that we learned to give them. The horns rarely changed equipment, but we had this wonderful ability to move our hand in the horn bell.

I remember Munch, the conductor of the Boston Symphony, came to Chicago as a guest conductor. We knew the Handel Water Music, and I said to the horn section, “Let’s give him that French treatment. We all know what the French sound is like.” So we came to the opening of the Water Music and had agreed to hold our horn bells up and open our hands, tuning accordingly. We thought it sounded awful because it was so bright. Munch said to the orchestra, “Horns, stand up. I have been conducting all over the United States, and when we play the Water Music it sounds like baritone horns.”

Herseth: The point you’re addressing is the ability and willingness to cope with the great variety of music that goes by on this assembly line. The programs go by each week and you grab what you can before the next batch comes along. Versatility comes from a motivation and a love of music. We all know players who say, “This is my part, and this is the way I play it.” You have to be motivated to want to get that music to sound the best that it can. Part of motivation is keeping an open mind about musical styles, so you adapt your own personal style.

When you have conductors coming from all over the world you learn very quickly that you don’t play for this guy the way you did for that French guy two weeks ago. The motivation and the love of music to want to do the best you can, not just play your part. Play it the same way whether it’s Debussy or Wagner? That’s trash.

Farkas: When a magazine says, “There’s no sound like the Chicago Symphony,” you’re going to try to maintain that reputation.

Herseth: If you’re wondering why I was late today, it was my practice routine. I’m still missing the last hour. People say: “You get a day off like any businessman. You get Sunday off, don’t you?” I say, “Well, on Sunday maybe I don’t have a concert, but I’d better practice, because on Monday, we might be going to Milwaukee.” When you’re working full-time you cannot practice every day as you would like. We had four concerts this weekend. We’re basically over-performed and under-rehearsed. You have to find time to practice the fundamentals.

Farkas: If you want to be a master of your instrument, first you have to be a slave.

Herseth: If I’m playing with the first horn, I always have an instinct to adjust to the other player.

Farkas: We’d be playing a passage, and I’d say, “Oh my gosh, I’m playing my notes a little longer than theirs.” By the time I’d shortened mine, they’d have lengthened theirs. We met halfway. It happened so fast the audience didn’t even hear it. In one or two notes, we adjusted to the same length, whether we believed in it or not.

Herseth: . . . even with little discrepancies of pitch and balance. A good friend of mine, an American who lived and worked in Europe for a long time, came to hear a concert some years back — I think it was with Leinsdorf. He had never heard a big-time American orchestra play a big-time tune. Of course they played great, but he said, “The thing I really noticed was how fast adjustments took place: balance, pitch, rhythm, everything. Even matching articulations.” He said he couldn’t believe how quickly those little adjustments were made.

What influence did conductors have on the development of the Chicago sound?

Farkas: Frederick Stock was relatively unknown in those days because recordings were poor. In Chicago he had a great reputation, but nobody outside of Chicago knew him. He had a big repertoire, and in a single year he would program everything of Strauss, the nine Beethoven symphonies, four Brahms.

Herseth: The records show that he did more new music than the so-called champions of new music. Of course some of his new music is now old music.

Farkas: He influenced the sound in a fatherly way. He got mad at one trumpet player, but the worst thing I ever heard him say was, “This isn’t the conservatory.”

Herseth: I’ve been trying to avoid such a line ever since I heard it.

Farkas: Then came Kubelik. I don’t think Kubelik contributed to the brass sound; he was a string player. For the brass the best thing to do was to keep in the background. He didn’t develop the brass section except for our pianissimo.

When Reiner came along, he demanded a dynamic contrast we don’t hear from students today. I accuse my students of having two dynamic levels: a soft mezzo-forte and a loud mezzo-forte. Reiner didn’t say much about intonation; he didn’t have to. With you two guys on the ends and us in the middle, we couldn’t help but find our niches.

Jacobs: The principals in the brass set the amount of dynamic flow and the style of phrase. In the brass there has to be someone who sets the pattern, and we go based on what we hear. This Chicago Sound is based primarily on the guidance from our principals.

What concerts do you particularly remember?

Farkas: I remember once in Boston we played a Berlioz overture, Corsair, then the Brahms Third, and finally Ein Heldenleben. Everything went perfectly on the first half. Then in Heldenleben, things were still going well. Pretty soon it went through the orchestra like a wave: “We’ve got a no-hitter going. God help the guy who misses anything.” Reiner’s eyes were getting bigger. I sweated through those last 10 measures.

We got through it; it was about as close to a flawless concert as I’ve ever seen. Reiner would always conduct a concert, take his bows, and go to his dressing room. That night when we came off the stage, there was Reiner, tears running down his cheeks, shaking hands with the orchestra members. He said, “All my life I have dreamed of a perfect concert; tonight we had one.”