Sousa’s Capitol Boyhood

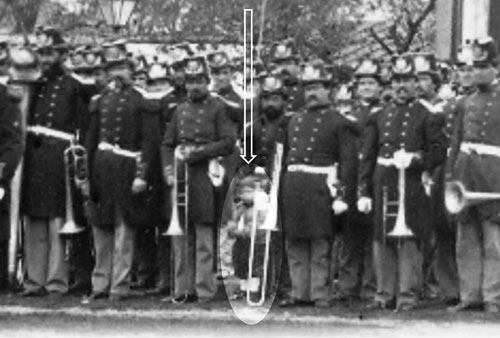

John Philip Sousa was born in 1854, the third of ten children, and grew up in Washington in and around the Marine Band rehearsal hall and parade ground.1 Sousa’s father Antonio was a trombonist in the United States Marine Band, the band that often played for the chief executive and traveled to Gettysburg on the same train with him to march in the parade and play at the cemetery where the immortal address was delivered.

Lincoln’s Marine Band, showing Sousa peeking out beside his father. Taken by Mathew Brady.

Young Sousa attended schools within blocks of his home and studied the violin. The boy vividly remembered the events surrounding the assassination of President Lincoln, especially how hard his father took the news. Businesses and schools were closed on the day of Lincoln’s funeral. Following the service in the White House, a massive procession of 15,000-20,000 led by the Marine Band was formed to bear the President to the Capitol where he was to lie in state. Church bells tolled from early morning and minute guns fired throughout the day. The date was April 19, 1865, and John Philip Sousa was there.

Just four weeks later, a massive Grand Review of the Armies marking the end of the Civil War was held in Washington. It lasted two days with more than 80,000 soldiers marching in a series of parades. Sousa recalled this thrilling event in his 1905 novel entitled Pipetown Sandy. Photographs and prints captured the scene as President Johnson, General Grant, and members of the cabinet looked on as each brigade passed a huge reviewing stand in front of the White House. The band and drum corps of each brigade marched to a spot opposite the reviewing officer, who was positioned next to the President. The groups played the great martial music of the time – Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!, The Battle Cry of Freedom, Yankee Doodle, When Johnny Comes Marching Home, and The Battle Hymn of the Republic. As the next brigade approached, its band would continue the music, adding greatly to the spectacle.2

Sousa the Professional

Early on, Sousa played violin in theater orchestras (including at Ford’s Theater), served as a pit conductor in early vaudeville, married, and built a reputation as a composer of operettas. His star continued to rise and in 1880, at the age of 26, he began leading The President’s Own U.S. Marine Band. Sousa rapidly transformed the band’s performance quality, instrumentation, and repertoire. The marches he composed and conducted, including The Rifle Regiment, Semper Fidelis, and The Thunderer were all well received by the public.

Marine Band on Tour

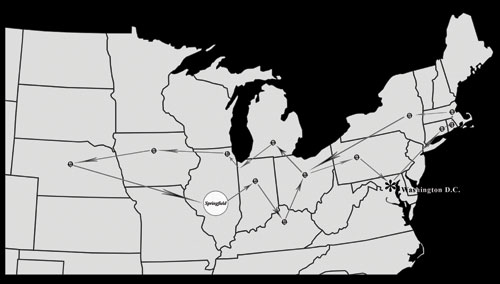

Sousa’s popularity soared, and people nationwide clamored to hear Sousa and the Marine Band in person. Up to this point, the Marine Band performed only in the Washington area, but popular demand and Sousa’s persistence, led to the group’s first tour. A 34-day tour began on April 1, 1891, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, traveled north through Massachusetts, Rhode Island, west to Albany, New York, on to Ohio, Michigan, Chicago, and further west to Iowa and Nebraska. A performance in Springfield, Illinois marked the beginning of the Band’s eastward route, which carried it through Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and home to Washington for the final performance at Lincoln Hall. In all, they played 43 concerts in 32 cities.

Lincoln’s Springfield

The matinee program in Springfield on April 25, 1891, took place at the Chatterton Opera House, jammed to the rafters. The scene was described as “one of the most fashionable audiences ever assembled in the capitol” according to the Daily Illinois Register. Impressive on many levels, the concert program included an overture, the movement of a symphony, soloists, ballet music, Sousa’s own hilarious Stag Party humoresque, patriotic selections, and Sousa marches – all beautifully performed. It was also visually impressive, featuring the 42 musicians wearing their elaborate and handsome military uniforms: scarlet full-dress coats trimmed with blue braiding and gold and white epaulets, blue trousers with a scarlet stripe down the outer seam of each leg, and white gold-spiked helmets.3

Just prior to the final selection on the program (Hail Columbia), Illinois Governor Joseph W. Fifer took to the stage and glowingly praised the performance by declaring it “delightful” and of quality not heard in Springfield “in a very long time.” He mentioned that the tour schedule precluded Sousa and the Band from visiting the Lincoln tomb but they would honor his memory with a visit to the Lincoln Home immediately after the concert. He extended an invitation for all to attend “an even better concert than this one, if such a thing is possible.” Following a rousing ovation at the conclusion of the concert the band was transported in omnibuses to the Lincoln Home, where over a thousand neighborhood residents had gathered. Sousa and the Band favored the crowd by playing Hail Columbia followed by Nearer My God to Thee, which undoubtedly brought back many fond and lasting memories of Mr. Lincoln, because Springfield considered him one of their own.

Meet Mr. Lincoln by the author.

Sousa, the Governor, and the band members were then escorted into the residence, where they were introduced to Mr. and Mrs. Oldroyd, the current occupants, and given a guided tour of Mr. Oldroyd’s collection of Lincolniana.4 After the tour, the Governor made a few additional remarks and Sousa followed by leading the band in his distinctive arrangement of The Star-Spangled Banner featuring the trombones and lower brass near the end.5 The band was transported back to the St. Nicholas Hotel before catching a train for Decatur, Illinois, where they appeared that evening.

Sousa and the United States Marine Band toured again the next year, beginning at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and heading west to California and then back to DC after playing 72 concerts in 38 cities over seven weeks. This tour did not include a performance in Springfield. At this point in time the lure of a career with his own civilian band was very tempting to Sousa, and he gave his final Marine performance on the White House lawn on July 24, 1892.

The Sousa Band

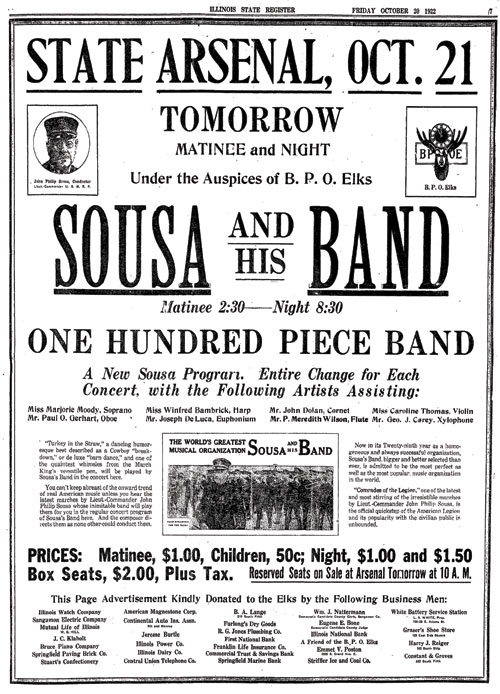

The Sousa Band was formed in New York City a short time later and existed until his passing in 1932. Musicians came from all over the world to audition and play with Sousa over the years. Virtuoso trombonist Arthur Pryor, who also served as Sousa’s assistant conductor, was called the “Poet of the Trombone.” Another performer was soprano Estelle Liebling of the Metropolitan Opera, whose students later included Beverly Sills and Meryl Streep. In 1922 Meredith Willson, composer of The Music Man, was Sousa’s principal piccolo/flutist when the band performed at the Illinois State Arsenal in Springfield.6 And perhaps the most important star soloist was Herbert L. Clarke, considered the world’s greatest cornetist. In the band’s history, traveling 1.5 million miles and being heard live by more than 50 million people are incredible statistics, considering that travel was done exclusively via train and ship. In all, the Sousa Band performed a staggering 15,623 concerts and marched only 8 times. In essence it was a concert band.

A Sousa newspaper ad from 1922 listing a young Meredith Willson.

Sousa and Springfield

In all, Sousa appeared 13 times in Springfield – once with the Marine Band and 12 more times with his own band. This city was certainly important to him, and Lincoln was a key reason. In April 1895 he again toured the Lincoln Home. It is unclear whether the Sousa Band members accompanied him, but his signature appears in the guest register now held in the Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum’s collection.7 That day Mr. Sousa went out of his way to make the visit. His time was limited because there was a concert scheduled for that evening in Jacksonville, Illinois at the Grand Opera House.

The year 1906 was especially important to Springfield since he not only conducted a concert on March 6 at the Chatterton’s Opera House but returned later that year in October to appear with the band for six days at the Illinois State Armory Music Festival, drawing 40,000 people to 13 concerts.8 On October 23, 1920, Sousa returned yet again to tour the Lincoln Home and this time also visited the Lincoln Tomb.9 On his last appearance in 1927, Sousa conducted the 55-member Springfield High School Band during intermission in two of his most famous marches – El Capitan and the Washington Post. At the conclusion of the concert, he posed for a photo with the group along with the elementary band and presented them with an engraved silver cup as a memento.10

Lincoln’s Meaningful Music

Abraham Lincoln was not a musician, but he did sing in church and elsewhere. He loved all sorts of music – cradle songs, ballads, hymns, dancing jigs, opera arias, anything by Stephen Foster (the leading composer of the day), and, of course, weekly band concerts. He intuitively understood the importance of music and everything it could do to enhance the lives of people. In virtually every book in the vast Lincoln literature, Dixie is said to have been a favorite song. The tune was, in fact, popular in both the North and South. In the final days of the war he asked bands specifically to play it on several occasions. Carl Sandburg said that “Lincoln wanted it to be a goodwill song of the reunited States.”11 As a boy Sousa most certainly heard it often and later made a band arrangement that he played on concerts from 1895 to 1930, sometimes repeatedly on the same program as an encore, thrilling his audiences. He also used snippets of the melody in his musical fantasy The Blending of the Blue and Gray (1887).

In 1861, Julia Ward Howe wrote lyrics to John Brown’s Body, a tune that had been around and known for some time. She titled it The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Lincoln heard it many times but on one occasion, it was special. On February 22, 1863, President and Mrs. Lincoln attended the first anniversary meeting in Washington of the Christian Commission held that evening in the Capitol Building. The meeting was to raise funds to support soldiers and their families, not unlike the Wounded Warrior Project of today. A man known as the “Singing Chaplin,” Rev. Charles McCabe, spoke about being imprisoned at the infamous Libby Prison, where he taught the song to the other prisoners. As he sang it for the President and the other dignitaries, the entire audience spontaneously stood and joined him along with a band located in the gallery. Before the last note had died away Mr. Lincoln called out, “Sing it again!” It was repeated immediately, Mr. Lincoln reportedly standing – singing, tears streaming down his cheeks.12 Ever since, the Battle Hymn, considered by many to be our national hymn, has become closely associated with Abraham Lincoln, who became one of the last causalities of the Civil War. Rev. McCabe sang the song for Lincoln once more at his funeral in Springfield at Oak Ridge Cemetery in May of 1865. Sousa did not make a free-standing arrangement of this piece but highly praised the lyrical verses written by Julia Ward Howe in a 1924 article – the third in a series of 22 published in newspapers throughout the country – entitled Songs of a Century that Never Grow Old.13 In his autobiography he wrote about the irony of the Battle Hymn being a southern tune and Dixie composed by a northerner.

Existing sources do not tell us if Sousa ever performed Dixie in Springfield, but it was always in the musicians’ music folders ready to play as an encore or on short notice. Such was the case following the February 21, 1899 Springfield concert. The next afternoon in Kansas City, Missouri, it helped to avoid disaster.

A crowd of 12,000 was on hand to dedicate a new Convention Center. As the concert was about to end a man in the balcony wanted to hear the scheduled trombone solo by Arthur Pryor. Pryor had not performed either in Springfield the evening before, or that afternoon, due to illness. Herbert L. Clarke stepped in to cover for him. The audience misunderstood the man’s shout “Pryor!” as “fire!” A stampede toward the exits began. Sousa urgently whispered “Dixie! Dixie!” calmly turning toward the audience conducting it through three times as people returned to their seats. Newspapers across the country reported the incident.14

Sousa never performed Dixie and the Battle Hymn together on the same program. In early March 1932 Sousa found himself in Reading, Pennsylvania to conduct an anniversary concert of the Ringgold Band. After a rehearsal and banquet he retired for the evening to his Abraham Lincoln Hotel room, later suffered an unexpected heart attack, and passed away at the age of 78. Twenty years after his death, in 1952, 20th Century Fox released Stars and Stripes Forever, a movie of Sousa’s life written by screenwriter Lemar Trotti, who had written the script for Young Mr. Lincoln starring Henry Fonda many years earlier.15 As with most Hollywood films, the historical record was altered for dramatic effect. But in this case, the elements of an important scene were based on fact and depict a full performance of Dixie followed immediately by Sousa (played by Clifton Webb) conducting a wonderful rendition of the Battle Hymn arranged by composer Alfred Newman. Sousa speaks to the crowd saying:

“We would like, with your permission, to play one more selection. [Sousa motions to a black choir to step forward.] It has long been a source of satisfaction here in the South, that on the night of General Lee’s visit to General Grant’s headquarters at Appomattox, the Marine Band in Washington, of which I was later to be Leader, marched to the White House to serenade President Lincoln. On this occasion, one of jubilation for the North, of defeat and despair for the South, Mr. Lincoln asked for only one tune – that which you have just heard – Dixie. In return for that compliment, we will now play, assisted by the Stone Mountain Church Choir of Atlanta, another tune which has come to be identified almost exclusively with our late President.”16

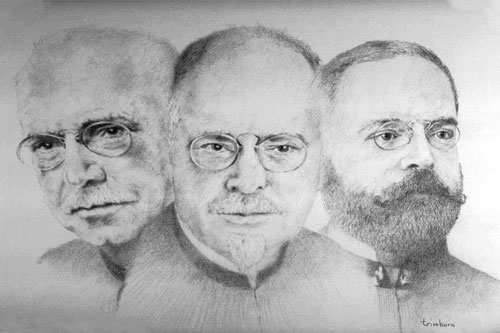

Sousa Triptych by the author – Sousa as he appeared in Springfield over the course of 40 years.

Meaningful Connections

Some may question a Sousa-Lincoln-Springfield connection, saying that Springfield was simply a convenient performance stop on its many tours taking the Sousa Band back and forth across the country. However, Mr. Sousa, and indeed on several occasions his entire band, went out of their way to visit the places most closely associated with Abraham Lincoln – his hometown, residence, and grave – all to pay the deepest respect to a revered American.

That said, music is the key connection between a king, a president, and a city – Sousa, Lincoln, and Springfield. All three continue to help define, represent, and sustain America’s identity to the world. The stories of the interconnected aspects of a culture shape its unique character. They, now more than ever, are important to our country as a nation, helping to remind us of who we were as people in the past, are now, and may continue to be in the future.

Notes

1 According to grandson John Philip Sousa III, a Mathew Brady photograph of the Marine Band taken in 1864 captures “a very small boy whom we presume to be my grandfather. He is virtually invisible” standing next to his trombonist father Antonio. Jon Newsom, Perspectives on John Philip Sousa (Library of Congress, 1983) 136.

2 Sousa wrote three novels; The Fifth String (1902), Pipetown Sandy (1905), and The Transit of Venus (1920). In the 1905 work he has the main character “Sandy Coggles” describe in detail the Grand Review of the Armies including a reference to the recent assassination and his father’s reaction – “Lots of flags had crape on ‘em. One of the guv’ners sed it was cause Mr. Lincoln had died. An’ that wuz mighty sorrowful to ev’rybody aroun’, to say nuthin’ of poor ol’ dad.” Sousa, John Philip, Pipetown Sandy (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 105) 195-204. See also: Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time (Rinehart & Company,1958) 280-281.

3 Daily Illinois State Register, April 26, 1891, 1.

4 Oldroyd’s collection, amassed over a 20-year period, included nearly 2,000 books, medals, pictures, badges, sermons, eulogies, and Lincoln mementos. Visitors were charged an admission fee and through the mail could obtain a “box of relics such as pieces of Lincoln Home bricks, apple and elm trees, roof shingle, dining room floor and ceiling plaster.” Oldroyd moved his collection to Peterson House across from Ford’s Theatre in 1892. James T. Hickey, The Collected Writings of James T. Hickey (Illinois State Historical Society, 1991) 190-196. See also: Wayne C. Temple, By Square and Compass: The Building of Lincoln’s Home and Its Saga (Ashar Press 4000 limited numbered, 1984) 97-108.

5 Daily Illinois State Register, April 26, 1891, 1.

6 Interestingly the size of the bands Sousa conducted increased over the years along with his popularity. The Marine Band of 1891 that performed in Springfield numbered 42 musicians and by 1922 grew to the 100-piece Sousa Band that performed there at the Illinois State Arsenal as noted in newspaper advertisements. See Illinois State Register, October 20, 1922, 7. See also Warfield, Patrick, Making the March King: John Philip Sousa’s Washington Years 1854-1893 (University of Illinois Press 2013) 117. Always resplendent in military style uniforms, Meredith Willson, the principal flutist, recalled that he felt he had “scaled the heights and the world was his apple wearing his Brooks Brothers uniform,” coincidentally the same company that tailored President Lincoln’s coats, sadly including the one worn to Ford’s Theatre the night of his fatal attack. See: Meredith Willson, And There I Stood with My Piccolo (University of Minnesota Press, 2009) 34. See also: magazine.brooksbrothers.com/dressing-presidents.

7 Cornelius, James M. “Research Request.” Message to the author on July 26, 2016. E-mail.

8 The Music Festival concerts were performed Monday through Saturday October 1-6,1906 (six days), two concerts each evening with an additional matinee on Saturday for a total of thirteen performances. Illinois State Journal, June 17, October 2, 7, 1906.

9 During the World War I era Sousa held the rank of Lieutenant Commander in the Navy Reserves, and he and the band members were welcomed to Springfield by a joint committee representing the Chamber of Commerce and Sangamon Post 32 of the American Legion. He and the musicians were given a tour of the city, including visits to Lincoln’s Home and Lincoln Tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery. There were two different programs performed at The Illinois State Arsenal on this occasion; one at 3:00 p.m. and another that evening. Both concerts were under the auspices of the Crippled Children’s Aid Society with proceeds to go to provide medical attention in the area, some children being treated at St. John’s Hospital. Daily Illinois State Journal, October 24, 1920. 11 See also: Illinois State Journal, November 10, 1927, 8.

10 See also: Illinois State Journal, November 10, 1927, 8.

11 Sandburg, Carl, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years IV, (Harcourt Brace, 1939), 184.

12 Covered extensively in the classic work on music and Lincoln during the Civil War period by Bernard, Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War (Caxton Printers, 1966) 218-220. There is little doubt that the Battle Hymn greatly affected Lincoln and that he held it in high regard. The lyrics connect the clear hand of providence to explain the meaning and outcome of the war. Ultimately however, he chose a different interpretation, as represented in his Second Inaugural – what some have called a sermon and I call a symphony. Lincoln believed it was a providential chastisement for the national sin of slavery of which both North and South were guilty. In balancing these views Lincoln demonstrates the challenge and appreciation for the mysteriousness of providence. See also: Newsom and Soskis, The Battle Hymn of the Republic; A Biography of the Song that Marches On (Oxford University Press, 2013) 98-99.

13 Sousa actually wrote an earlier article in the same series on John Brown’s Body, lamenting that during the war the “new” lyrics by Howe intending to replace those of John Brown never really caught on with the soldiers. In his follow up article on the Battle Hymn he went on to opine that the lyrics by Howe were some of “the most beautiful pieces of verse to have come out of our country.” Cincinnati Inquirer wire service articles, June 6, and July 20, 1924.

14 Bierley, Paul E., The Incredible Band of John Philip Sousa, (University of Illinois Press, 2006) 137.

15 A Southerner by birth, Trotti’s work in the film industry consistently promoted the theme of reconciliation between North and South as he assumed the role of unofficial ambassador. The Sousa film is acknowledged as helping to establish the inevitability of the growing civil rights movement. See: Barker & McKee ed. 2011. A “Professional Southerner” in the Hollywood Studio System. American Cinema and the Southern Imagery (122-147) University of Georgia Press.

16 Trotti (Producer). Koster (Director). (1952). Quotation. Stars and Stripes Forever [Motion Picture].

Bibliography

Abraham Lincoln: The War Years IV by C. Sandburg (Harcourt Brace, 1939).

American Cinema and the Southern Imagery edited by Barker & McKee (University of Georgia Press, 2011).

The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song that Marches On by J. Stauffer and B. Siskis (Oxford University Press, 2013).

By Square and Compasses: The Building of Lincoln’s Home and Its Saga by Wayne C. Temple (Asher Press [Limited], 1984).

The Collected Writings of James T. Hickey: from Publications of the Illinois State Historical Society, 1953-1984 by James T. Hickley (Illinois State Historical Society, 1991).

The Incredible Band of John Philip Sousa by Paul E. Bierley (University of Illinois Press, 2006).

John Philip Sousa: American Phenomenon by Paul E. Bierley (Prentice Hall, 1973).

Lincoln by David H. Donald (Simon & Schuster, 1995).

Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War by K. Bernard (Caxton Printers, 1966).

Making the March King: John Philip Sousa’s Washington Years 1854-1893 by Patrick Warfield (University of Illinois Press, 2013).

Perspectives on John Philip Sousa by J. Newson (Library of Congress, 1983).

Stars and Stripes Forever (motion picture). Producer: L. Trotti, Director: H. Koster. (United States: 20th Century Fox, 1952).

Washington in Lincoln’s Time by N. Brooks, edited by H. Mitgang (Rinehart, 1958).

Acknowledgements

Without the assistance of the following, this article would not have been possible. Thank you to all! Justin Blanford (Superintendent, Illinois Department of Natural Resources), James M. Cornelius (Curator, Lincoln Collection at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum), Timothy Good (Superintendent, Lincoln Home National Historic Site), Mark L. Johnson (Historian, Springfield Historic Sites), Scott Schwartz (Director, Sousa Archives at the University of Illinois), and especially Curtis Mann (Manager, Springfield Public Library Sangamon Collection).