This article originally appeared in the April 1976 issue of The Instrumentalist.

During five days of master classes in Burlington, at the University of Vermont’s Mozart Festival, Julius Baker worked with 29 flutists, some Juilliard graduates, some still in college, and some housewives, to improve their playing. A great deal of time was devoted to the most obvious shortcoming of many flutists — a lack of fully projected, dead-center sound supported by a solid and steady air flow. Baker continually stressed the importance of playing long, high tones to achieve a fuller, better sound. Us-ing full vibrato, the students were told to play four descending chromatic high notes, holding each note four counts.

For three days I listened to students diligently practice this high tone study and the results were astounding. Those who formerly were a half tone flat and couldn’t be heard beyond the first row definitely had acquired a more confident, in-tune sound. The exercise will help the flutist when he plays Beethoven’s 7th Symphony, for example, where he seldom moves off high E or F for the entire work.

A "big round tone" is advocated by Baker, who has been with the New York Philharmonic for 11 years. Most flutists who have had any orchestral experience are well aware that the flute solo in the first movement of Dvorak’s "New World" Symphony, for example, will never be heard above the first violin section if the sound is not only supported but projected.

Another daily study which Baker recommends for tone is playing long notes at p < f > p for nine counts. Baker also pointed out that the student should not take a breath when his lungs are still half full, but must release all the air before inhaling again.

As for technique, he suggests the Taffanel and Gaubert arpeggios and scales (Exercises 1, 2, and 12 of the Grands Exercices Journaliers). These are to be memorized and practiced full-tone, all gears ahead, with the metronome set at 104. He also encourages the grouping and regrouping of scales to emphasize the importance of phrasing. Baker urges students to phrase over the bar line, the way one normally plays a Bach sonata, or for that matter, most music.

Naturally, a great part of tone quality is related to intonation and pitch. During the course of the master classes, tuning was the first rather difficult step to performance because of the efficient air conditioning system. Nevertheless, Baker encouraged the student (at the beginning of his performance) to play with the head joint pulled out so the flutist had the option to push it in if need be.

Baker’s technique for tuning no doubt comes from many years of adjusting to orchestral oboists. First he hits the note, somewhat like a string player would pluck a string when tuning. After he has established the pitch, he extends the note into a long tone. Baker is adamant about starting low and working the pitch up. His embouchure, then, acts like the fine tuner on a string instrument.

Vibrato and Tone Color

During the question and answer periods many students expressed a preoccupation with vibrato and tone color, although few of them were ready for work on the latter. Julius Baker is an artist at both. He had no easy advice on either topic. When teaching vibrato he sets the metronome and has the student release a quarter of the air on each beat, while sustaining a four-count long tone. The tempo is then doubled so that four impulses eventually become eight, and so on.

Baker can instantly spot a vibrato with a "tight throat" and recommends eliminating vibrato from the throat by having the student go back to playing without vibrato until it comes naturally. Indeed, he remarked that many of his students were never taught vibrato, it just happened. (Considering the concentrated high note studies that he recommends, I can see how muscular control could eventually evolve into a natural vibrato.)

Baker’s solution for achieving tone color was not as precise as his answers on vibrato. After all, tone color is a highly developed skill which includes a number of variables — timing, dynamics, width of vibrato, phrasing, breath control, and articulation. The best illustration of superb tone color can be found in Julius Baker’s own playing. When playing one particular passage over and over again for different students, he never once played it the same way. The changing nuances were not in the structure of the music, but in the color and poetry of Baker’s playing.

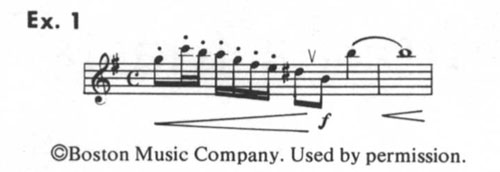

Perhaps we can see how this skill is acquired by watching Baker work with his students. Although one of the more advanced students seemed to be playing the second movement from Handel’s Sonata in G Major very well, Baker stopped her at a particular passage (see Ex. 1). The lower B, an up-beat to the high B, sounded dead. Baker wanted vibrato on that eighth note — not too much, or it would become a dotted eighth, but enough for the note to come alive. At first the player overcompensated, and just as Baker forewarned, the eighth note was too long. So he asked her to forget that he had ever mentioned the problem, and she played the note exactly right.

Bach

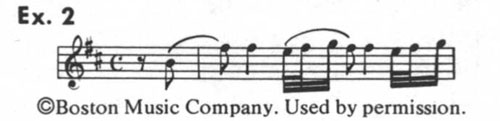

From 1947-1965 Julius Baker was a member of the Bach Aria Group and is renowned for his knowledge of ornamentation. Thus, although the Vermont Festival centered around Mozart, many of us chose to play Bach sonatas. The opening measures of the Bach Sonata No. 1 in B Minor took up an entire morning (see Ex. 2).

Half of the students played the 32nd and 16th note figure like a triplet, while the other half simply could not make the proper contact with the accompanist for a harmonious entrance. (The entrance is tricky because the pianist relies on the downbeat given by the flutist during the piano’s 16th rest.)

Baker, demonstrating his solution several times, suggested a slight bow forward and back on the eighth rest, prior to the beginning pickup. He neither looked at the pianist furtively nor raised his elbows like a bird taking off in flight. Though hardly noticeable, this slight body movement always brought the accompanist in with precision.

The third problem encountered in the same two measures came with the first F#, which the flutists invariably jumped on and then left hanging. Baker explained that were this string music, both eighth notes (B and F#) would be played with an up-bow. Since the up-bow is usually weaker, it follows that the F# quarter notes on the down-bow are more important, and stronger.

The first movement of Bach’s Sonata No. 6 in E Major presented problems of a different nature. At least ten different editions of the sonatas are available to the student. Baker recommends the Boosey & Hawkes edition because it more closely reproduces the ornamentation printed in the Bach Ge-sellschaft than any other edition.

One brief example is typical of the discrepancies in many editions. The Bach Gesellschaft shows it as

while one of the other editions shows it as

There is an extreme difference of opinion here. Bach obviously wanted the emphasis on the trilled low F# of the third beat and not the E. A mordent on the E followed by a breath mark shifts this emphasis. Such discrepancies warrant careful evaluation by teachers in suggesting the right edition of the Bach sonatas to their students.

Fingerings

Fingerings were not first priority in the class, although Baker demands correct finger placement with the thumb pad of the right hand centered between the first two keys. Like most professionals, his fingers stick magically close to the flute. Many of us were astounded by one girl who played the entire Doppler Fantasie Pastorale Hongroise with her fingers raised at least two inches off the keys. The handicap in no way fettered her determination to keep up the tempo, but her job would have been so much easier had she relaxed her fingers on the keys.

Baker also mentioned that he does not believe in fake fingerings, but later qualified his statement by saying that their use is a matter of personal discretion. In the faster orchestral passages, some fake fingerings are practical. Baker suggests that the middle finger F# is to be played only in E-F# (or vice versa) trills and rapid passages.

Instruments

Julius Baker plays a Powell, Haynes, and Muramatsu flute, interchanging head joints from time to time. One of his flutes has what is called a split E key, a bridging device which pulls down the lower half of the G key when high E is fingered. The effect is the same as an open G and is especially helpful in slurs (such as high E-A) that tend to break.

Many of the students were playing the Cooper-Powell flute. Cooper is a flute maker in London who has been working on corrections for the existing Boehm system for many years. His scale is much more precise and eliminates tacky intonation problems of the standard flute, such as the flat low E-B register. The Cooper flute is an eighth of an inch shorter than the traditional Powell. Richard Jerome of the Powell Flute Company in Boston informs me that in a year’s time, the Cooper flute became as popular as the standard Powell model.

When trying out another student’s Louis Lot flute, Baker stopped several times to remark on the absence of the Bb lever key, the one depressed by the side of the first finger of the right hand. On fast runs this key is extremely useful.

Perhaps the most unforgettable experience of those five days was hearing Julius Baker pick up his flute and play a scale, whiz through Chaminade, or produce the most beautiful A in the world. A twentieth century person, he believes in the cassette recorder as the flutist’s tool for bio-feedback. "Listen to yourself," he says. "You can’t buy talent. You can’t add to it. You can develop it."

Recommended Readings

Boehm, Theobald. The Flute and Flute Playing. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Chapman, F.B. Flute Technique. New York: Oxford University Press.

Quantz, Joachim. On Playing the Flute. Translated by Reilly. New York: The Free Press.

Recommended Studies

Bitsch, Marcel. Twelve Etudes for Flute. Paris: Leduc.

Bozza, Eugene. Fourteen Arabesques. Paris: Leduc. Casterede, Jacques. Twelve Studies. Paris: Leduc.

De Lorenzo, Leonardo. Nine Grand Concert Etudes. Frankfurt: Zimmermann.

Genzmer, Harold. Twelve Neuzeitliche Etuden. Vol. 1 and Vol. II (13-24). London: Schott.

Taffanel & Gaubert. Grands Exercices Jounaliers. Paris: Leduc.

Scores

Bach, J.S. Bach Gesellschaft. Lea Pocket Score No. 10, Bryn Mawr, Pa.: Theodore Presser, Co.