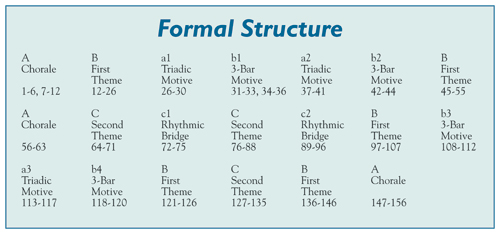

Editor’s Note: As composers wrote about their favorite neglected band music, the piece most often mentioned was Peter Mennin’s Canzona. This analysis first appeared in the January 1989 issue of The Instrumentalist.

Few major composers have written only one piece for band, never to return to the medium again. Such is the case with the late Peter Mennin, who composed Canzona in 1951. Considered a major work at the time, it is still a standard in the band repertoire nearly four decades later, playable by grade 5 high school and university bands.

Peter Mennin was born on May 17, 1923 in Erie, Pennsylvania, and developed an interest in composition at an early age, completing his Symphony No. 1 at 18. This interest led him to composition studies at Oberlin in 1940 and later at the Eastman School of Music.

Early on Mennin was recognized as an outstanding American composer. His free-spirited approach fell into no particular school of compositional style; he allowed the basic materials of his craft to dictate direction, rather than forcing ideas into a predetermined form. This approach did not keep him from creating solid musical structures in his works. Mennin expressed his ideas fluently, regardless of form.

Mennin once told a writer for Music Clubs Magazine, “I like to work at long stretches, from early morning to night. I compose without a piano or any other musical instrument. I think that a work is completely scored before I put a note on paper.” Apparently he was able to decide on form and orchestration in his head and then simply transfer the mental score to paper. This procedure seems to have worked well for Mennin, because his output is an enviable one by any standards. His works include nine symphonies, a piano concerto, a cello concerto, works for chamber orchestra, string orchestra, chamber ensembles, and solo piano, and one composition for band.

After concluding his compositional studies, Mennin received a Guggenheim fellowship in 1948 and another in 1956. He taught at the Juilliard School of Music prior to being named director of the Peabody Conservatory at the age of 35. He served in this capacity from 1958 to 1962, when he was named president of the Juilliard School. He spent the remainder of his career there, guiding the school’s move to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in 1969 and serving until his death in 1983 as an administrator and composer.

Mennin had progressive views on the training of musicians and conductors. It was his contention, as reported in the May 1958 issue of Musical America, that most conservatory training for conductors was mere stick-waving. While at Peabody he began a program to assist gifted young conductors in developing the skills necessary for professional success. A committee that included Charles Munch, Eugene Ormandy, Fritz Reiner, Max Rudolf, and George Szell oversaw this three-month program. Mennin believed that students seeking careers in music needed to make music at the highest levels, and he was willing to go to great lengths to provide such programs.

As a practicing composer, Peter Mennin held strong opinions about the compositional process. Because he believed that composition was an individual matter, he disliked the idea of compositional schools; it was unthinkable for him to write in a style interchangeable with that of another composer. Mennin firmly believed that a composition should state something personal and that it must come from within. In the November 1980 issue of Musical America, Charles B. Sutton quoted him as saying, “A composer can’t rely on outside stimuli. He must have inner stimuli. I would continue to be a composer whether I were here or in Timbuktu.” Fortunately, Mennin followed his own advice in his approach to composition.

Walter Hendl’s article, “The Music of Peter Mennin” in the Juilliard Review, Spring 1954, provides some information about Mennin for the interested conductor. Hendl suggests that “all of Mennin’s craft is directed toward achieving the dramatic whole.” The composer is adept in his use of motives and their exposition, and does not try to fit his ideas into anything resembling sonata form.

Mennin’s melodies are generally diatonic; he uses half-step progressions to quickly change tonal centers. The composer shows a predilection for the intervals of the diminished fifth and augmented second, using the latter to create major/minor ambiguity. His melodies are exceedingly long, with no particular antecedent-consequent phrase structure and no strong dependence on the bar line.

Mennin is perhaps most interesting in his approach to harmony. In “The Music of Peter Mennin,” Hendl states that “some triads have been restored to important levels of power and given contemporary significance by such means as added notes, bitonality, and a kind of inflection unknown in the 19th century.”

Mennin uses instrumental choirs to create contrast in Canzona. He treats the woodwind and brass choirs as distinct units, retaining their individual identities even when the full ensemble is playing. Percussion instruments are sparsely scored, in the manner of orchestral percussion writing.

Commissioned in 1950 by Edwin Franko Goldman through the League of Composers, Canzona was published by Carl Fischer, Inc. Goldman had already enjoyed a long career as the conductor of a professional band, which gave him the opportunity to play much of the music that had been written or transcribed for concert band. Along with many other bandmasters Goldman longed for a high-caliber concert band repertoire. He believed the future health of the concert band depended on the development of such a repertoire by current composers. At the time Canzona was commissioned, most composers felt they could not advance their careers by writing for concert band, and few were doing so. Commissioning composers was one of the only ways Goldman and others could encourage first-rank composers to produce works for concert band.

In choosing the title Canzona, Peter Mennin intentionally evoked an earlier compositional style, giving it a 20th-century definition. His use of the term does not imply a strict adherence to any of the 16th- and 17th-century instrumental forms of that name, one of which eventually evolved into sonata form, but he seems to have adopted the sectional nature of the early canzonas as a structural principle for this work. More generally, the composer himself acknowledged the influence of Renaissance polyphony on his compositional style. Some of his harmony could be described as polyphonic, in that it results from the carefully blended interaction of melodic lines. The alternation between the homophonic style of the chorale section and the canonic imitation of the thematic sections is another organizing principle. On the largest scale, the chorale serves an important unifying function, delineating the work’s major sections.

Mennin treats thematic material less by development than by repetition with subtle rhythmic and melodic variations. He uses this concise approach in Canzona, varying the basic material throughout the work by augmentation, transposition, canonic imitation, and timbral alteration. Virtually all the melodic material in the piece is derived from the dramatic opening, a bold chorale in polychords.

.jpg)

This music requires a forceful, accented style and should be played at Mennin’s indicated tempo (quarter = 126). Balance is essential to this passage and should not be sacrificed for the sake of dynamic effect. It is possible to analyze this beautiful chorale using traditional harmonic analysis, but the non-tendential movement of the chords defies such an analysis. The sounds seem to have been conceived sheerly for the qualities they represent, and their effect on the listener is magnificent. These marvelous chords depend heavily on precise balance, which is important to stress in early rehearsals of the piece. The written C# by the first cornet and trumpets in measure five should be attacked firmly to maintain intensity and tempo.

The second statement of this brilliant chorale occurs at letter A, with the upper woodwinds added to the scoring. Here the percussion parts should receive emphasis by using decisive accents, which enhance the natural forward momentum of the material. Mennin already begins to achieve variety by rhythmically modifying the chords in the second statement. Though the harmonies achieved through contrary triadic motion are similar to those in the first six measures, the slight changes in orchestration – use of upper woodwinds and sparse percussion – show the ability of the master craftsman to create additional tension and momentum. It is this beautifully conceived chorale that offers a firm means of establishing form within the work.

The first theme appears at letter B. In a program note published by Carl Fischer, the composer calls it a “broad melodic line supported by powerful rhythmic figurations.”

.jpg)

Here the conductor has to propel the melodic line forward in a cantabile style, interpreting it expressively by using tension and motion in the forearm and baton. At the same time the staccato accompaniment should be clean, precise, and subordinate to the thematic material in the upper woodwinds and the first cornet. Mennin quickly reveals his penchant for long melodic lines, this one stretching for a full 14 measures plus an additional eighth note. Balanced phrases are non-existent, and there is little sense of influence from the barline on the theme. This ingeniously conceived first theme is full of syncopations and melodic repetitions, all smoothly blended into an arresting melody.

One of the compositional devices used extensively in Canzona is canonic imitation, carefully crafted to create both melodic and harmonic interest. The first such occurrence is in measure 21, 10 bars after B, in the low brasses and reeds. The conductor should provide a precise downbeat to assure accurate rhythmic placement of this syncopated thematic material. The entrance is in two octaves with a tonal center of D minor. At letter C the imitation ends abruptly with a pleasing though unexpected rhythmic diversion.

One factor contributing to the unity of Canzona is Mennin’s reuse of material with such craft that the listener is barely aware of the close relationship between what is new and what was previously heard. An example of this occurs at letter C, where the composer introduces a series of parallel triads in first inversion in the Bb clarinets and an octave lower in alto and tenor saxophones; it is essentially accompanimental material, which the composer is now bringing to the fore as melody.

.jpg)

Here the conductor should dispense with the espressivo beat pattern so critical at letter B and instead conduct in a crisp, staccato style. The incessant eighth notes in the low reeds and low brass require light, delicate attacks, achieved with a small beat pattern whereby the tip of the baton stops concisely on each count. This eighth-note material in the bass is intervallically related to the first theme and is another example of Mennin’s thematic economy.

Although the three-bar melodic motive at letter D sounds like a new theme, it closely resembles the first theme in its syncopations, stepwise melodic motion, and cantabile style. It is, however, more rhythmically vigorous than the first theme.

.jpg)

Mennin follows its introduction by repeating the idea at measure 34 before returning to punctuated, rhythmic triads at letter E. A third statement of the three-bar motive reappears within an increasingly thickening texture at measure 42 as the composer drives toward the magnificent canon at letter F based on the all-important first theme. It is easy for the conductor to lose sight of the importance of the melodic material within the texture at letter D, unless he makes some interpretive decisions prior to the rehearsal. As before, an espressivo beat pattern combined with a careful balancing of the accompanimental figures yields excellent results.

The composer brings his creative abilities to bear at letter F, developing material he has thus far presented. He offers the first theme in a four-octave span in the key of F minor, followed one bar later by a low brass and reed entrance a perfect fifth lower on Bb. Here the conductor should simply stand aside and enjoy the glorious counterpoint, intervening only to maintain proper balance between the melodic lines.

Mennin modifies the first theme at measure 52 as he approaches the dramatic return of the opening chorale. He rescores this restatement for the entire ensemble at a fff dynamic; the rhythmic variation of the chords further demonstrates the supreme subtlety with which Mennin treats material and creates interest. Conductors should enhance this exciting return of the chorale with large, accented motions of the baton, allowing for the increased dynamic level indicated on the score. For the listener this second appearance of the chorale provides a second pillar in the overall construction of the piece.

The second theme, the beautiful, cantabile melody at letter H, is based on chord tones from the first theme but is in a contrasting, lyrical style.

.jpg)

Again parallel triads, this time in second inversion, are used as harmonic accompaniment; and syncopations provide tension and release. The light, separated bass figure recalls earlier material.

During score study the conductor should sing the melody many times to develop his own interpretation of it; he should not allow the sustained half notes in the clarinets and French horns to overpower the beautiful melodic statement by the flutes and oboes. The thinly scored texture at letter H provides a welcome contrast to the preceding chorale, revealing Mennin’s masterful ability to keep the proportions of the structure clearly in mind throughout the composition. There is no spot where the listener feels that the composer is rambling or searching; every note has an important role to fill.

Another short rhythmic transition appears at letter I, this one sufficiently new and different to generate tension leading up to a second presentation of the second theme, the cantabile melody at letter J. As he did with the first theme, Mennin presents this melody in canonic imitation at measure 81 followed six bars later by a second entrance a minor third lower. Conductors need to balance the melodic lines so they do not lose expressiveness; one helpful approach is to experiment with the number of players on each part.

After another rhythmic interlude at letter K, the first theme returns in augmentation.

.jpg)

This time the theme is laced with new melodic material in the upper woodwinds.

.jpg)

Baton motions full of energy and intensity are required to draw Mennin’s thick, dark melodic line from the ensemble. He has indicated the desired balance at letter L: the bass line should clearly predominate.

Six bars after letter L, in measure 102, the composer emphasizes the augmentation of the theme by presenting three bars of it in canon. The entrances are layered so that although they are melodic in nature, their interaction provides a harmonic foundation for the return of the three-bar motive in measure 108.

The woodwind choir at letter M serves as a bridge that leads to a new contrapuntal section at N, setting up the most fascinating counterpoint yet provided. Numerous melodic elements emerge in stretto at letter N: the three-bar motive, followed immediately by the first theme in canon. It is easy to overconduct this intense passage of music. Alerting performers to the im-portance of not playing each note ff will lend clarity to the texture of this thickly scored section.

A stroke of genius follows at letter O as the composer begins the second theme in augmentation, then reverts to its original rhythmic values after two bars.

.jpg)

This is followed by a brief triadic entrance in the cornets, whose contrary motion against the bass line recalls the opening chorale, another subtle unifying device.

The first theme makes its final appearance at letter P in canon with the entrances a fifth apart as before. Mennin cleverly drops the dynamic level here, allowing the conductor to rebuild the intensity as he approaches letter Q; conductors should carefully rehearse this passage to assure a gradual crescendo from letters P to Q. The climactic appearance of the chorale at the end of the piece, with a thematic fragment superimposed in the upper woodwinds, is simply breathtaking and constitutes a final structural pillar for the work. Allowing a small amount of space between the chords in the brass, saxophone, and lower reed chords at letter Q will produce a cleaner, more vibrant interpretation of this exciting ending. Winds and percussion should listen carefully to balance each other, and the ringing of the cymbal crashes should not be dampened in any fashion. This extended chorale leads to the punctuated fanfare on a D major seventh chord at measure 154 by trumpets, horns, and upper woodwinds that concludes Canzona.

Will Canzona be regarded as a masterwork for band in years to come? The piece does not sound as contemporary today as it did when first published in 1954; more recent band compositions give the percussion section an importance equal to that of the woodwinds and brass. The technical requirements for players are not as great as those of many contemporary works. It would be a mistake, however, to overlook this marvelous piece amid today’s new works. Canzona is challenging music for the band medium, written by a major composer; as such it merits the attention of every serious band conductor. Careful study of the score will continue to yield many rewards for performers, conductors, and listeners alike.