I have always loved preparing to go back to school in the fall. I must also confess that I enjoy browsing the office supply stores to stock up with new pencils, pens, folders, vinyl sheets, rulers, tape, stickers, and other items I use in lessons. September is the time for teachers to organize the year’s calendar, set new goals for themselves and their students, plan the fall and spring curriculums, and accept new students.

Calendar

Before planning your calendar, check your state’s Music Educator’s National Conference schedule on the internet. Most state web pages list audition deadlines and materials, as well as regional and statewide clinic dates. Then check the web pages of the local youth orchestra and school district for their schedules. This will give you an idea of when students will be available for lessons, flute choir rehearsals, and performances.

We should support local music programs by planning our schedules around community events; this avoids putting students in the awkward position of having to choose between commitments. While private lessons and flute choir participation are equally as important as band concerts and clinics, it is easier for us to provide scheduling flexibility.

Active flute choirs often give two formal concerts each term, and many flute choirs repeat each concert at other venues. This is a great idea because your studio gets additional exposure in the community, and it is an excellent recruiting tool. A good plan for the fall term is one concert around Halloween and another before Christmas. Many flute choir compositions fit well into this holiday-themed scheme. In the spring, early March and mid-May are good performance times. Many school districts schedule fall and spring breaks that you may need to consider when planning your calendar.

Choosing which days to teach is one of the big decisions that private teachers have to make. When I was teaching flute pedagogy, a student told me that she was going to teach all the beginners on Monday, the intermediate students on Tuesday, and the advanced students on Wednesday; that way it would be easier for her to plan and remember the curriculum for one day at a time. If only life were so simple!

New teachers in the process of building a studio are often put in a position of teaching whenever students want a lesson. This type of schedule is not an effective use of your time. As soon as you have a large enough studio, you will want to organize the week around your family life. Many states allow private teachers to give lessons in the public schools during the school day utilizing the time during ensemble classes, lunch periods, study halls, and before and after school. This is ideal because it allows teachers to be home with their own children and to have a more regular evening meal schedule.

At the beginning of each term I list the weeks that I will teach lessons and hold flute choir rehearsals on a large white board in my studio. I also list dates, times, and locations of all performances. Any last minute changes during the term are also noted on the white board.

After the first lesson I encourage students or parents to transfer that schedule into their planner. Having the entire fall or spring planned at the beginning of the term provides better studio-wide participation. An alternative to the white board is to list all studio activities on your web page or designate a domain on one of the social networking web sites for the information. This works well with older students but is inappropriate for younger ones, although their parents may appreciate it.

Contracts

Many teachers find that having a studio contract between the student and teacher is helpful. Personally I never felt the need to develop one. I have two rules that I mention when students sign up for lessons:

1. Call me 24 hours ahead if you are going to miss your lesson or you will be charged for the lesson.

2. Lesson fees for the entire month are due at the beginning of the month or you can pay by the lesson.

I do not teach lessons on credit. Time is money.

In the many years that I have taught, only two students have failed to pay. If you take a new student who does not abide by the two rules above (24 hour notification for a cancelled lesson and failure to pay), then drop them sooner than later. You will find that students who do not have the discipline to follow these simple rules will not be students who can learn to play with control and discipline.

.jpg)

Accounting

At tax time you will need an accurate record of each student you taught and the dates and lengths of their lessons. I generally teach about 14 lessons per student per semester. This averages out to be four in September, October, and November and two in December. These numbers do not include college-credit lessons, which are regulated by the department guidelines.

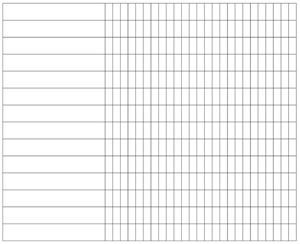

I use two forms in order to keep accurate teaching records. The first is a general information sheet that I ask students to fill out each fall. It includes their current contact information and tells a little about the student. The second is one that I mark at each lesson.

Use one or more of the boxes page for each day that you teach. If you teach on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday, staple the sheets for each day together and place them in a vinyl sleeve. This small packet easily fits into a flute bag so you can have the information that you need at any time. In the longer box, fill in the name of the student on the first line and his quick contact information on the second line. Above the small boxes, place the date of each lesson for the fall or winter term. When a student receives a lesson, mark an X in the box. I use one X for a half hour lesson and XX for an hour lesson.

In the second box directly under the first one, note if the lesson was paid in advance or paid on a specific day. If a student pays for four lessons at the beginning of the month, then I place PD in four boxes under the appropriate date. At the end of the term I tally the number of lessons given by the amount of the lesson fee. This gives me my earned income information for the Schedule C form of the U.S. tax forms.

New Goals

When planning the year, don’t forget to schedule some time for you. This time could take the form of private instruction from a teacher that you admire, or it could be attending a concert, masterclass, or lecture. This will keep your skills current and provide stimulation to develop your creativity. Set goals for you and for your students.

There are two kinds of goals: long and short term. Students need both. A long term goal might be to enter a concerto competition in the spring. A short term goal might be to learn all the melodic minor scales by memory this month.

First Lesson of the Fall

When students return in the fall, check the cork placement in their headjoints. It is quite possible that the cork moved over the summer. Also check whether the pads are seating properly. Miniscule air leaks around the pads can cause an airy tone, tempting the player to squeeze the keys too tightly in order to make the flute speak. It is better to get the flute repaired at the beginning of the term than just before an important concert or audition.

Assessing New Students

When students begin lessons in the fall, I evaluate their skills to set goals for them. These are a few of the most common weaknesses I encounter.

Body Position

The most common problem is how students sit or stand relative to their music stands. Band rooms are set up with the music stand directly in front of the chair, so students think they should sit with their shoulders parallel to the music stand in a position very similar to their clarinet buddies. Because the flute is an asymmetrical instrument, this presents a problem of balancing the flute and still being able to see the music. Students often lower the end of the flute towards the floor, tilting their head to the right. Not only does this cause pain in the neck and right shoulders, but it inhibits the wind pipe. This may contribute to a small, out-of-tune, pinched tone.

The solution is to have students stand as if they were serving a volleyball, with the left foot in front and the right foot in back. When sitting, the chair is rotated to the right 45 degrees, and the student sits with the feet in the volleyball serving position. The abdomen should face to the right, and the upper body should spiral to the left. While many students can successfully achieve this position, the end of the flute is often positioned back too far. The end of the flute should be even with or in front of the player’s nose. This position encourages players to rotate their head slightly to the left. Be sure that they bring the flute to their lips rather than bringing the chin down to the flute.

Thumb Position

An incorrect left-hand thumb position can lead to tension and pain. The left-hand thumb should be straight and point to the ceiling. The crease in the first knuckle should touch very close to the bottom of the thumb key. If the student touches the thumb key with the tip of their thumb, the left wrist may protrude and be rounded, which can cause carpal tunnel syndrome over time. To check a student’s thumb position, stand behind them on their left side to watch them play.

Articulation

Many students have been taught to double and triple tongue by a non-flute playing teacher. Most enlightened flute players think of tonguing as being a horizontal movement rather than a vertical one. The teeth are separated and the tongue moves through the teeth touching the top lip for the attack. Remember – the tongue releases the air. If the air comes first, the attack sounds hooty. There are several good syllables to say, but my favorite is Thi-Key. The goal is to position the tip of the tongue forward and high. If the student has not experienced this concept, he will quickly be able to achieve success in a few weeks with some drill at each lesson.

Vibrato

Vibrato control is another issue that affects performance and audition success. It should start at the beginning of the note, but too many students start the note and then add the vibrato. Unless designated by the composer, the strongest part of a note is at the beginning. Record students so that they can hear what they are doing. Often the sheer action of playing takes precedence over active listening.

Rhythm

Many students struggle with counting and rhythmic performance. This stems from a lack of understanding of the difference between simple time and compound time. Simple time is when the beat is divisible by 2, as in 2/4, 3/4, and 4/4. Compound time is when the beat is divisible by 3 as in 3/8, 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8.

Plan to include some rhythmic reading in each lesson to develop this skill and rhythmic understanding. To check a student’s level of understanding, ask them to rhythmically read from a sight reading manual. There are several good ones on the market such as Rhythm Spectrum by Ed Sueta and Rhythmic Training by Robert Starer. A student recently told me that her college theory department had simplified the theory course so that the music theater majors could pass the course. In the aural skills portion of music theory, the curriculum no longer includs any sight singing or rhythmic drill. It makes me wonder who wins in this situation. The answer is simple: No one.

For some unknown reason, students today are very literal in their musical performance. All notes are glued together and are played without inflection or nuance. There is little knowledge of style periods and how this relates to performance practice. The solution to this problem is huge and will be addressed in future columns.

The Joy of Teaching

When the fall teaching schedule begins, you will renew your relationship with students you may not have seen for several weeks or months. Many of them will have attended summer music festivals, camps, and masterclasses during the time away from you. I always look forward to hearing about their summer activities and experiences.

One of my informal studio rules is, if you attend a masterclass and there are handouts, be sure to bring one back for me. Students enjoy explaining these handouts and sharing their newly-gained information. This discussion is very important because it helps the student put the summer experience into prospective. While they may have discussed their summer with their parents, only another musician will truly understand what they have experienced.

Of course I am extremely pleased when they have had a successful time and felt well-prepared as they ventured into the greater music world. For me, one of the greatest joys of teaching is knowing that I have taught a student to teach themselves, so that one day, they can leave my studio and know what they are doing.