If you want to improve the rhythmic clarity and intonation of your ensemble, employing some type of chunking technic practice is required. One of my favorite things to do when sightreading through a composition is to play one count followed by a rest of the same duration. This is more challenging than it appears. First this will show you if each member of the ensemble actually knows where each beat is as those who aren’t sure of where the beats are will be playing in the rests. It may take several passes to get the performance with the rests clean, but the results are worth the practice time.

National Anthem in 6/4

Once the students can play chunking by beat followed by a rest, then chunk by two beats followed by a rest. Since the National Anthem is in 3, then I would also chunk by 3 beats. Chunking like this also improves the phrasing if you remind students of the strength of the beat rule which when playing in three, the strongest beat is one, two is less, and three is least, and pick-ups are played softer than what they lead into. One of my colleagues teaches the strength of the beat in time signatures of three by saying STEP, Tip, toe.

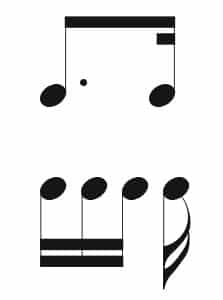

If there is a consistent mistake on one count, then examine the notation of that count and teach how the subdivision works. For example, if the pick-up is not accurate, have students fill in the dotted eighth with three sixteenths and play the following reminding that this beat is a subdivision of 4s rather than 3s.

At least for one time through, in the case of the National Anthem, have students fill in each beat with four sixteenths. Understanding the subdivision of a beat is something that the best musicians do for a rhythmically accurate performance and to ensure that all ensemble attacks are synchronized. While playing 2/4 in 4/8, 3/4 in 6/8 etc. is rare in the wind literature, many slow movements in orchestral works are subdivided. This is a skill that wind players need when playing in orchestra and chamber works. When filling in, varying the articulation patterns alters the placement of the tongue in the mouth which may result in a better sound. First practice with T and follow with the K and Hah (breath attack/no tongue). Practicing the T and then the K improves the double tongue stroke also.

Intonation is vastly improved if each ensemble member plays on the ictus or beat-point. Unfortunately, weaker or less experienced instrumentalists play early on the beat while the most experienced ones will play on the beat. What this means for intonation is that the weaker players are setting where the intonation will be instead of the stronger players. One of the by products of this type of chunking practice is that it helps each player play on the ictus. Demonstrate in your conducting patterns where the ictus is and show students how to do this themselves.

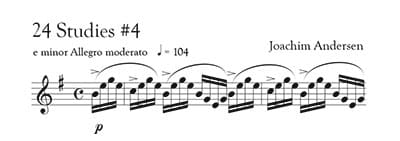

Another type of plucking is to play only certain notes in a beat. This is another subdividing tool to play rhythmically and also to develop the art of recognizing note-patterns. In the following example play only the first sixteenth of each beat. Notice that all but two have an accent or little diminuendo above them. Since this excerpt was written in the Romantic era, this accent is realized as a little diminuendo. Lingering on these notes brings the melodic line forward. The other notes are played as an accompaniment.

Next play the first two notes of each beat. Notice that all of the second notes are E. On the next play through play the first three notes of each beat. Then start from the ending of the beat playing the third and fourth sixteenths and then the second, third, and fourth sixteenths. Obviously, the second, third, and fourth notes are accompaniment notes, and all have the same two pitches – E and G. Usually after practicing plucking these notes, students readily see the pattern and can play the entire passage easily and with skill.

Chunking Grouping Patterns

Pedagogues Marcel Tabuteau, legendary oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and William Kincaid, legendary flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra taught that notes lead to one so in the above Andersen example, the phrasing is 1, 2341, 2341. When chunking by fours, explore other patterns such as 3412, 4123, and 1234 followed by a silence. This puts the stress and coordination of the fingers in different places, and when playing what is written, the quality of the performance is always better.

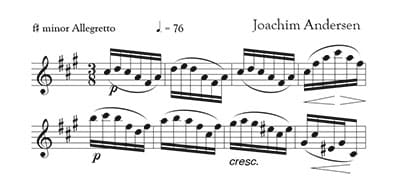

The following etude offers challenges because it is written in F# minor.

Playing an F# minor scale before beginning work on the section is beneficial. Next, employ a practice technique called breaking down, where each note is repeated several times by tonguing each note four times followed by three times and two times. When it is time to tongue each note once only, employ other syllables besides T (K, Hah, TK/TKT). This slows the passage down so students have time to think about the pitch and each fingering. This is especially good to do with a section of the ensemble to check that all are reading and fingering the correct notes.

Change the Meter

With any etude that is written in compound meter (background beat is divisible by 3’s), it is possible to change the meter to simple meter. In this case changing 3/8 to 2/4 allows us to regroup the sixteenths into two triplets. When applying this technique in measures 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7, the middle note of this group is an upper neighboring tone, and the last three notes are a palindrome – meaning that the notes are the same going forward as backwards except for measure 8, which is a broken arpeggio.

Bonus Idea

While this is not a chunking practice technique, try to find some way to make a slurred exercise into a tongued exercise. Beginning and intermediate level students should single tongue, and high intermediate and advanced students should double tongue. This may be done with tonguing each note one or more times. Tonguing exercises should be done with the metronome to ensure development of speed.

My students enjoy exploring these techniques because they work. When progress can be seen and felt, students are apt to continue these practice techniques on their own, and they soon develop a fluid technique.