Teaching students how to shape their oral cavity and embouchure can be one of the most challenging aspects of clarinet pedagogy. Even professional clarinetists benefit from daily work in this area. The art is in finding language and reference points appropriate to the student’s level, then layering further developments at an appropriate pace.

Preliminaries

From the beginning, I encourage players to form the embouchure just prior to inserting the clarinet mouthpiece. Many students insert the mouthpiece first and then form an embouchure around it, which is problematic for several reasons. By inserting the mouthpiece first, a student ends up with an aperture that is much too big. This encourages players to assert control with the jaw (biting) instead of using the lips, and prevents them from properly focusing the airstream into the mouthpiece. The mouthpiece first approach also frequently leads to having too much splayed lip (especially the lower lip), which diffuses lip contact and control points on the mouthpiece. A splayed lip also leads to biting and slightly shrinks the vertical space in the oral cavity, decreasing total resonance. Many players find that taking in increased lower lip results in a much more homogenous sound, and large leaps become more seamless.

It is also essential to emphasize the concept of Breathe, Set, Play. The embouchure and support must be set in place prior to beginning to play. Many students begin playing while the embouchure and support are still stabilizing, producing wild fluctuations in tone quality and pitch. An easy way to teach this feeling is to have students play a note, and then snap your fingers to have them stop the tone with their tongue. Freeze everything in place, including the air and abdominal engagement. This feeling of embouchure and air engagement set in place is necessary prior to playing any note. Ask them to memorize and establish this feeling prior to retracting the tongue to begin the note.

Beginning Embouchure Development

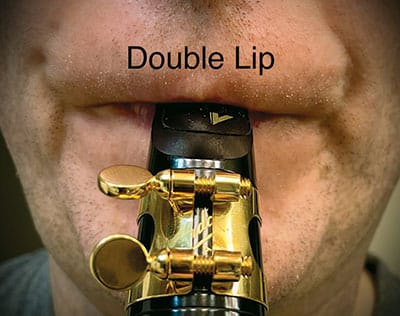

A double lip embouchure is a good place to start with beginners. If students are able, I ask them to flatten their chin first, keeping it in place as they proceed. Once the chin is flattened, simply have them open the jaws slightly, wrap the lower lip over the lower teeth, wrap the upper lip over the upper teeth, and then insert the mouthpiece. For most players, the lips should wrap over the teeth right up until where the lip turns into skin, although this can vary depending on the size of their lips.

While some professionals use double lip, most do not. The benefit of starting with double lip is primarily that the lips are mirror images of each other, and it typically prevents students from biting to control the instrument. A double lip embouchure also puts a player’s tongue in a good default position without having to discuss it. Ask students to notice what position the tongue goes to when forming a double lip embouchure. It should feel like a ski slope where the back of the tongue is raised higher than the rest of the tongue. Double lip also encourages students to create maximum vertical space in the oral cavity as the extra lip forces the jaws slightly further apart.

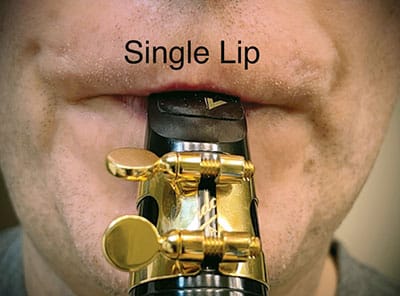

After the embouchure has stabilized, you can switch students to the single lip, explaining that the single lip embouchure should mimic the double lip as closely as possible. In fact, when I am teaching, I will form a double lip embouchure with the clarinet in my mouth, and then, without removing the clarinet, switch to single lip to emphasize how similar they look. The only difference is that the upper lip moves from under the top teeth to curling under itself and pushing down along the front teeth.

When students switch from double lip to single lip, they will need to train the upper lip and learn to activate the depressor septi nasi muscle that runs from the base of the nose to the upper lip. It should feel as if they are pressing the top lip down onto the mouthpiece.

One good strategy for practicing upper lip placement is to form an embouchure, insert the clarinet mouthpiece, and then, with a free hand, pick up the top lip, dry off the front teeth with a finger, allow the lip to stick to the teeth, and slowly allow the lip to slide down to the mouthpiece. This forces the bottom part of the lip to curl up and under slightly. When correctly done, the single lip embouchure should now look the same as the double lip – with the only difference being that the upper lip is curled up and in against the teeth rather than splayed over the top of the mouthpiece.

Another useful concept to introduce early is the idea that the lips should grip the mouthpiece evenly all the way around it. Ask students to form their embouchure (single or double lip) and then insert their thumb into the embouchure as if it were a mouthpiece. Ask them to seal the lips around it as if preparing to play and then check if they feel the lips gripping the thumb with even pressure all the way around. Imagine that the center of the lips are saying oo to help emphasize the even circular pressure around the mouthpiece. Most people will feel more pressure on the top and bottom portion than the sides. This is a simple way to introduce the concept of bringing lip corners in and that the lips should provide the bulk of the grip, not the jaws.

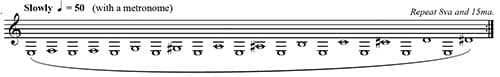

At this point in their development, students should be playing daily long tones. (An example of one is given below.) The specific exercise is less important than making sure students complete the daily study with a clear goal. Typically, I start them on the low E as a reference point, go to F, back to E, then F#, continuing the pattern of reference note followed by ascending chromatic note. I do this typically in forte whole notes at a speed where they can play four notes (sixteen beats) prior to needing to breathe until they reach the octave. I take this at quarter=50 but younger students may need to do this much faster. When breathing, take an entire beat, don’t try to sneak it in.

When introducing this exercise, I explain that it takes five minutes daily, and that even if they stop after this, they can say they practiced that day. However, if they skip this and practice other items, they can’t claim to have practiced. After establishing the importance and brevity of this exercise, I tell them to practice it in front of a full-length mirror. After learning the basic exercise, I add different skills every other week and eventually extend the duration. To keep them focused, I ask students to write the week’s instruction on a notecard and tape it to the mirror next to where their face is. A few examples (in order) include:

• Watch the mirror and make sure your chin is pointed/flat the whole time.

• Steady embouchure, nothing moves, pretend to be a ventriloquist.

• Keep the clarinet and clarinet mouthpiece centered.

• Press your top lip down onto the mouthpiece the entire time.

• Aim the air to your “mustache.”

• Grip the mouthpiece with your lips evenly all the way around.

• Make sure that each note matches the first note.

At this point the embouchure should be pretty stable, and teachers can add such variables as different octaves and dynamics. Students should keep and reuse their cards as a refresher on various concepts. This method helps to stay focused and work on one specific task rather than juggling multiple instructions at once. I begin with items that they can see in black and white and then move on to concepts that require more discernment.

To evaluate whether students are in a good basic position and potentially ready to advance in their development, try the following test. Have them play a C4 at a healthy mf volume. While they continue to hold C4, reach over and press the register key, and a moment or two later, add the side G# key without telling them exactly when you will press either key.

If the resultant notes come out right away without any issues (other than a bright tone) that tells you that the student has a good fundamental embouchure, tongue position, air direction, and air consistency. If the notes don’t speak right away, review consistent mf air, ski slope tongue position, and aiming the air towards the mustache.

Further Development

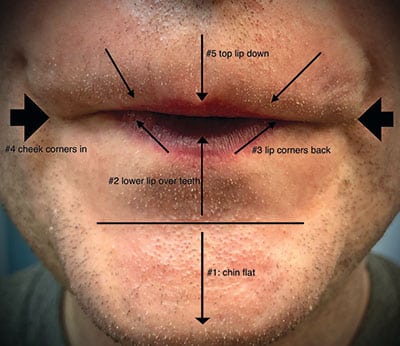

Once a student has a stable basic embouchure, I introduce Yehuda Gilad’s five step embouchure formation, although I like to switch the order of the first two steps from what he teaches. I find it unhelpful to start beginners with this teaching because it requires a sense of what the individual steps are adding up to and involves using muscles umfamiliar to many younger players. Five separate steps for people who are new to using these small facial muscles is too confusing. Once they have sufficient playing experience, we can delve under the hood to refine the embouchure. As students work through this list, make sure that once a step is completed it is glued into place and remains unaltered as they layer the further steps on.

In front of a mirror, with the lower jaw dropped open slightly:

- Flatten chin

- Bottom lip over teeth

- Lip corners back

- Cheeks in

- Top lip down

Step three should feel almost like a smile, where the lower lip draws taut along and against the lower teeth as if it were plastic wrap. Step four feels similar to someone coming up and squeezing the two sides of the embouchure inwards with their fingers. When students initiate step four, it should not undo step three at all (no bunched lower lip). Many advanced players have been told corners in and it can help to clarify the difference between step three and four. If you ignore or downplay step 3, you end up with a bunched lower lip protruding. If you ignore or downplay step four, you end up with biting.

To maintain a fast and focused airstream, students should next learn how to control the horizontal axis of the oral cavity. Drawing the cheeks in just behind the orbicularis oris muscle helps them keep more of a point to the airstream. In order to find this sensation, have students make a fish face in front of a mirror, and then with one hand press in the dimples that are formed immediately behind the orbicularis oris. These dimple spots should engage while playing.

The primary control for the vertical axis in the mouth is the tongue. While the double lip embouchure puts the tongue in a good basic position, the best position is a little higher and further forward. The ideal tongue position is automatically formed when saying eu, as you might do when speaking French. This moves the tongue up, primarily the center of the tongue, and also forward slightly. Have students say eu with confidence, hold the tongue in the resulting position, and then insert the clarinet and play a forte F major scale. Frequently, you will notice significant improvement in focus and robustness of tone. I have found that eu is so foreign for some students that they cannot satisfactorily find the position. For these students, I recommend using heee, or hissing like a cat as a starting point. This will at least help them find a higher tongue position which will result in faster and more consistent air.

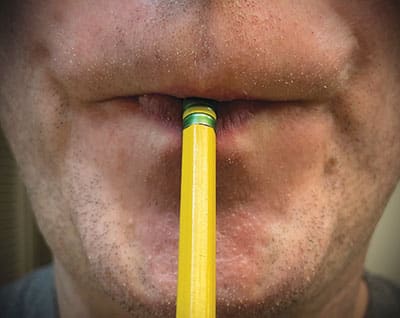

Finally, there is an exercise ties this together while refining the size of the embouchure aperture. Students will need a new wooden pencil with an unused eraser. When I first introduce this exercise, I tell students that I am unable to speak while demonstrating but will indicate with my fingers which step I am on. After demonstrating, I will verbally guide them through step by step.

- After forming a double lip embouchure, place the eraser in the center of the embouchure, as if it was a clarinet mouthpiece.

- Try to suck in the eraser for several seconds, as if sucking a really thick milkshake. This will draw the lips inward.

- While holding the lips in the resultant position, breathe in through the nose.

- Blow vigorously against the eraser, holding for three seconds while maintaining the lip position.

- Pull the pencil out of the embouchure, blowing the air with as much strength as possible without the lips collapsing.

There are a few things to keep in mind while doing this exercise. Only put the eraser part in the mouth and none of the silver portion. During steps 2 through 4, no air should actually enter or exit the mouth – let the eraser act as a plug.

Once this unorthodox series of movements is understood, ask students to hold the embouchure after blowing out all of the air in step five. Then, breathing through the nose, they should insert the clarinet, and play a forte F Major scale. It is critical that as they insert the mouthpiece, the embouchure stays exactly as it was formed from the pencil exercise. Nothing should move. This is frequently the hardest thing for students to get right. It can feel as if the embouchure aperture is so small that the clarinet won’t fit. This is not true, and they need to just trust it. This exercise is critical for developing strong lips with a small aperture that operate independently from the air stream. Typically, a student’s sound will be significantly more homogenous, focused and robust after successfully finishing this exercise.

Conclusion

The development of embouchure and oral cavity shaping can be one of the most challenging techniques to master for clarinetists. It can be all too easy for students to be confused even with clear instructions due to a lack of kinesthetic awareness. While these instructions are laid out in a sequence that I think makes the most sense, it can occasionally help to go slightly out of order to give students a win if they are having a hard time grasping a particular concept. Nothing is more frustrating than being unable to figure out how to move one’s body in a certain way or being unable to tell whether you are doing something correctly.

Though I begin with instructions that are more readily evaluated visually, students do need to quickly learn how to refine their kinesthetic sense. As frequently as I can, I provide clear reference points (such as double lip, fish face, and the pencil exercise) for students to check in with rather than relying exclusively on descriptive language. Students need to be able to self-direct and evaluate.

Remember that these instructions are not in fact the goal. I too often see students doing everything right according to their understanding of the instructions yet remain unaware of their undesirable tone. It should be clear from the start what these instructions are in service of, and that the instructions are always secondary to the ears. After all, the audience doesn’t know where your tongue is; they only care whether you have a beautiful tone that is resonant, even, focused, and in tune.