Question: Why does it seem that I play better during my flute lesson than I do when I’m alone in the practice room?

Answer: With a bit of self-awareness and a journal you can take greater control of independent practice and see more progress in your playing between lessons. First, it helps to understand how your brain works and develop a better understanding of your natural learning capabilities.

Playing the flute requires many types of thinking. Flutists have to be emotional and expressive, technical and analytical, physical and athletic. Every thought and action moves at lightning speed and in perfect harmony. When learning a new skill, people integrate new information and form mental connections by generating myelin. This is the fatty substance that wraps itself around neurons in the brain and strengthens the electrical impulses transmitted throughout the nervous system. Learning a new skill grows myelin, and more myelin strengthens the ability to learn.

There are five different levels of consciousness or brainwaves that we experience throughout the day. While reading this article, your brain is vibrating at 13-80 cycles per second in the Gamma or Beta wave. Right now you are conscious, awake and alert, processing information and performing daily functions; your thinking tempo is Allegro. You might think that the most productive time to practice is when your brainwaves are the fastest. Well, think again!

The next three brainwaves are slower and more restorative: Alpha (daydreaming), Theta (drowsy, pre-sleep), and Delta (unconscious, dreaming, sleeping). These waves are dancing between Moderato and Largo on the mental metronome. It is difficult to practice when your brain is in the drowsy Theta wave or completely asleep as in Delta wave. The daydreamy Alpha state offers some interesting possibilities. Think about all of the times you have floated away on a daydream – it feels good, comfortable, creative, and easy. When people ride an Alpha wave, they process four billion bits of information per second, compared to only 2000 bits of information within the faster Gamma or Beta waves.

The next aspect of deep learning to explore is called metacognition; this is the ability to think about your thinking. People do it all the time, yet unfortunately don’t always take full advantage of this inner awareness to make lasting change in their playing.

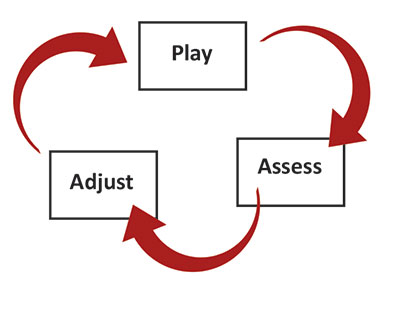

Amanda Leon-Guerrero describes metacognition as a self-regulation process and summarizes it perfectly by stating, “Self-regulation is the process of assessing progress in a given task, deciding what strategy will improve performance, implementing the strategy and evaluating again to determine if the set goal has been achieved.”

Why am I struggling?

Think about your struggles in the practice room. What is your practice routine like; what mistakes keep happening? Are you struggling to change your embouchure or hand position? What does that struggle feel like and what are you thinking about when you feel yourself begin to struggle?

Madeline Bruser describes three different types of struggle in her book, The Art of Practicing: A Guide to Making Music from the Heart. She states that students experience overstated passion, avoidance, and aggression in their playing. Does your tone go sharp every time crescendo through a phrase? Do you notice that you put off practicing etudes until the day before your lesson? Or perhaps, you squeeze the flute too hard during a difficult run or passage? These are examples of overstated passion, avoidance, or aggression.

With newfound self-awareness, you can take steps to break old habits and build new strategies that improve your ability to make positive changes to your playing. Look at challenges and struggles not as setbacks, but as gems to show you where to focus your attention and prioritize your practicing.

Learning expert, John Hattie describes the benefits of challenge as this:

Learning is not always pleasurable and easy; it requires over-learning at certain points, spiraling up and down the knowledge continuum…. This is the power of deliberative practice. It also requires a commitment to seeking further challenges – and herein lies a major link between challenge and feedback, two of the essential ingredients of learning.

What’s my mindset?

Carol Dweck, an expert in learning psychology research, has identified two types of learners. The first type has a fixed mindset; this student believes that the ability to learn a new task is inborn and limited. In contrast, the second type of learner believes that regardless of how difficult the material or problem may be to solve, it can be done. This is called a growth mindset. Dweck further explains: “Students with a growth mindset…view challenging work as an opportunity to learn and grow.… Students with a fixed mindset do not like effort. They believe that if you have ability, everything should come naturally.”

Analyze, Adjust, Repeat

Next, put this all together by observing your thoughts during your practice sessions. It is important to make a plan that helps you organize your time and choose what to focus on.

Step 1: Identify your struggle style

This might be overstated passion, avoidance, or aggression. Become familiar with your limiting tendencies to better recognize when you are falling into a rut and move yourself back into a more productive zone.

Step 2: Identify an area to change

Perhaps it is vibrato, octave slurs, a short technical passage, rhythmic motive, or articulation.

Step 3: Repetition

This is where things begin to come together. Set the metronome at performance tempo or slightly slower if needed. By repetitively practicing a small microburst, your brain will move into the slower, more meditative Alpha state, as well as develop a hyper-reflective, metacognitive process to identify and change your performance issues.

1. Repetition builds myelin.

2. Repetition assists your brain to move into the Alpha state.

3. Repetition allows you to metacognitively plan, adjust, and maintain the change you are seeking to make.

4. Repetition is a gateway to deep learning and helps you develop a growth mindset.

Step 4: Loop and Group

This is a time tested practice strategy that you may have already utilized in your practice sessions and it is how you add metacognition and personal observation to make lasting change to your playing:

1. Play a small technical pattern in tempo with a metronome.

2. Rest for twice as long as the technical pattern.

3. Repeat.

During the rest between each Loop and Group, analyze what happened. Don’t worry about getting it perfect at first, just observe. Where is the technical misfiring of your technique? How and where does your technique breakdown? What was the thought you had right before the mistake? Be curious. With the metronome keeping you focused, just observe your thoughts. In the split second before you repeat each Loop and Group, decide on an adjustment and apply it to the next round.

As you loop this technical microburst over and over (perhaps 20, 30, or even 50 times) your brain slows into the Alpha state and builds myelin that creates the change you seek between practice sessions. You are discovering new thought patterns that help you correct problems and make adjustments in the moment. This process allows you to integrate your cognitive (thinking), sensitive (sight, hearing, touch), and motor skills (physical coordination) into a powerful tool of deep learning.

Putting it all together

Finally, track your progress, stay organized, and strategize your weekly goals by keeping a practice journal. Throughout the semester, take time to ask yourself big picture questions and check-in with your progress. This will help you independently create a strategy for improvement, implement the strategy, and finally evaluate performance progress.

Bibliography

Bruser, Madeline. “Three Styles of Struggle.” In The Art of Practicing: A Guide to Making Music from the Heart. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1997.

Dweck, Carol. “Even Geniuses Work Hard.” Educational Leadership, vol. 68 (September 2010): 16-20.

Hattie, John. Visible Learning A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Leon-Guerrero, Amanda. “Self-regulation strategies used by student musicians during music practice.” Music Education Research, vol. 10, no. 1 (March 2008): 91-106.

Miller, Richard. Yoga Nidra: A Meditative Practice for Deep Relaxation and Healing. Boulder, CO: Sounds True, 2010.