The first time I played the Camille Saint-Saëns Carnival of the Animals, Volière (The Aviary) in public was when I was in graduate school at The Eastman School of Music. A regional orchestra had contacted my teacher Joseph Mariano to ask if he had a student who could play the famous movement. Mariano said yes and sent me to do the run-out program. Evidently the principal flute of this orchestra was ticked that the conductor did not like the way she played the movement, so I was greeted with anything but open arms. She insisted on playing first on all of the other movements and only let me play the Volière. This meant that I never got a feel of what it was like to play with the other orchestra members or for the acoustics of the concert hall. So, in the one rehearsal and the concert I picked up my flute and played the movement. I do not know why the conductor thought he needed to bring someone in because he conducted so slowly that anyone with a bit of training could have played it, and as the movement progressed he grew even slower.

The next time I played the Volière was at a summer festival. This conductor was known for “warming his fingertips” before a concert which meant that he drank a few shots of scotch before he went on stage. This particular evening, he had warmed his fingertips a bit more than usual. When he began the two-measure introduction, his quarter note was clicking along at about 100 rather than the usual 72 to 80. During the first measure as my heartbeat was increasing, I looked over at the principal cellist, and he mouthed, good luck! By the second measure I decided I was going to come in at the proper tempo and let the conductor find me. With the help of the cellist, we corralled the tempo, and the movement went well. This proved to be a good decision because after the concert the conductor thanked me for saving the movement.

While I have played this piece many times through the years, the two most interesting narrators I performed with were Ann Southern and Adam West. I loved Ann Southern from her movies and a stint on television, and while I had never seen Adam West as Batman, I knew who he was and was honored to be working with him.

Preparatory Work

Before embarking on the study of the Volière, flutists should have conquered the skill of double-tonguing. No matter which syllables are used, the tongue should be forward in the mouth with the K syllable as far forward or close to the top teeth as possible. There was a time when many were teaching some form of DaGa or DuGu; however, this method places the secondary syllable too far back in the mouth which means that speed and a lightness of the notes are lost. The tongue is free in the mouth, and both the T and the K are equal in execution so to the listener it sounds like a simple staccato.

The embouchure hole should be centered with the player’s aperture and the flute placed firmly in the chin. While tonguing, the headjoint should not move or bounce under the lip.

Each year during the Christmas holiday, I revisit one of the complete methods for learning the flute by one of the esteemed pedagogues. My favorites are by Popp, Soussmann, Altes, and Taffanel and Gaubert. A few years ago, I was rereading through the Soussmann/Popp and realized I had mistranslated a German instruction about double tonguing. I incorrectly thought it said to double tongue without the tongue touching any place in the mouth. This meant that the tip of the tongue was flapping through the air stream back and forth. I started working on this technique (using Thi-key syllables) and in about six months was able to tongue in this manner. I still use this technique because it offers increased speed and clarity. If you have never tried this technique, give it a chance because you may be able to add one more skill to your bag of playing tricks.

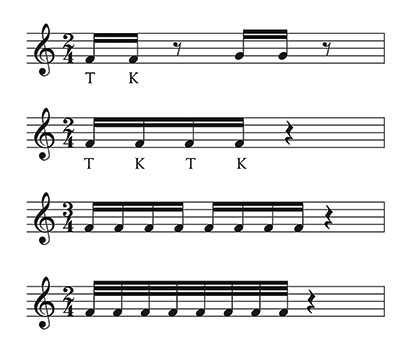

To learn the double-tonguing skill, begin by playing the following exercises on a scale. Pick a scale that utilizes the middle of the range such as F or G major. Notice that each exercise adds more notes until the flutist is playing eight notes on one beat or gesture. Learning to play eight double-tongued notes on one beat is the secret to playing this excerpt.

Because of their rhythmic training American flutists more often think in units of four sixteenth notes per beat. Many students have asked me if they played enough notes when playing eight notes per beat. This is a skill that must be drilled until students are thinking by eight notes rather than by four notes.

Since the flutist must double tongue at this very quick speed for six counts, practice a chunk of six groups of eight sixteenth notes followed by a rest on each note of the F or G major scale. Remember that tonguing in the extremes of range offers different challenges in changing the size of the aperture, so learn the double-tonguing concept in the middle of the range before practicing it elsewhere.

Double tonguing on the same pitch is easier than when the pitch changes on each syllable. Practice these rotations to learn this concept. Starting at the top of the scale and working down will help naturally drop the jaw for the lower range notes.

.jpg)

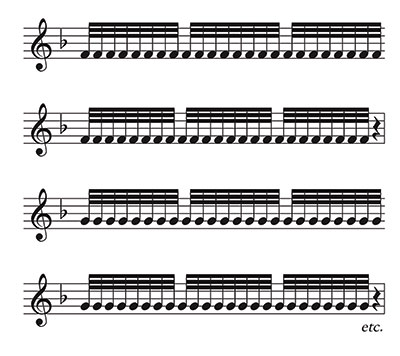

Use the following scale pattern from the Wilhelm Popp Flute School, Op. 205 (1873) as a template for practice. Insert a quarter rest after each group of eight notes. During the rest take a sip or conversational breath. Play each note twice with the double tongue (TK) at a mf dynamic. Since most students are comfortable playing by groups of four sixteenth notes, there will be a tendency for them to bounce the flute on the first of each group of beamed sixteenths. Work to bounce the end of the flute by chunks of eight notes. Repeat playing each note once with the double-tongued syllables.

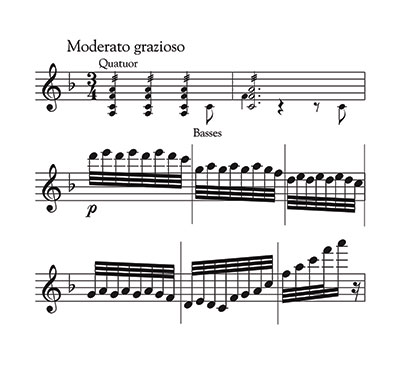

Chunking the Volière

After each group of eight notes, take a sip or conversational breath. Repeat chunking measures 3-12 and 19-22.

Putting It Together

Many flutists struggle with this excerpt because they are playing too loudly. Notice the piano dynamic. Because of the orchestration, flutists do not need to force or play loudly to be heard. The goal is to be light like a bird with a homogenous sound throughout the range. When playing the chromatic passages, try playing the entire scale while shifting your weight from the right back foot to the front left foot or if seated, rotate from the right sitz bone to the left sitz bone. Each time you perform this movement, review the exercises above, and this excerpt will become a joy rather than one to be feared.

* * *

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) wrote The Carnival of the Animals for a private concert in 1886. The 25-minute, 14-movement work is scored for two pianos, two violins, viola, cello, double bass, flute (piccolo), clarinet, glass harmonica (glockenspiel), and xylophone. In performances today, the strings are often augmented to include more players. The flute plays in only three movements: the Aquarium, the Volière (Aviary), and the Finale.

The Volière (Aviary) is the tenth movement in the set. The accompaniment begins with string tremolo for two measures before the flute enters. The string tremolos continue adding the two pianos first in a syncopated figure, then trills and a chromatic interchange with the flute. The tempo marking is Moderato grazioso. According to the manuscript, the chromatic scale the fourth bar after 2 should have a Bb so the full measure is a chromatic scale grouped by 8, 8, and 10 notes.