Intonation is a very important aspect of playing, whether you are performing as a soloist, recitalist, chamber musician or as a member of an orchestra or band. In this article I suggest ways for flutists and other instrumentalists to work on improving their intonation. It is something that should always be a part of practice and can be improved with careful listening and consistent work.

In an instrumental ensemble it is important to have members who listen carefully and adjust to each others’ pitch. Before tuning you should always be warmed up and the flute should be at playing temperature. When the flute is cold the notes sound flat. Therefore, if the flute is cold when tuning, you will go sharp as the instrument gets warmer. After you are warmed up, match the tuning note (usually A) perfectly and check several other notes or intervals as well. Assuming A is the tuning note, tune your A in the low octave and above the staff ( the A above the staff is more revealing because there is less flexibility in changing the pitch with airstream direction than on low A). Other good intervals to check are octave Es, Fs, and Ds. It is helpful to be aware of the tonalities in which you are playing. In order to make appropriate pitch adjustments for these tonalities try to imagine the chord underneath the flute line.

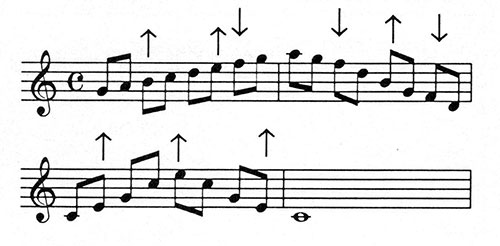

Scale practice is also important for improving intonation and to learn pitch flexibility. You should be sure the scale sounds in tune by singing the scale (mentally or vocally) and making corrections as necessary. Using a tuner for slow practice is helpful to increase awareness of individual notes on your flute that consistently register sharp or flat. Be sure to know the tendencies of the notes that are out of tune on your instrument and make the proper adjustments. The exercise in example #1 is meant to be played in all twelve major keys using Pythagorean tuning, which is used by string players. In this type of tuning, the third and seventh scale degrees in a major key are played higher and the fourth scale degree is played lower. The exercise below ( example #1) is designed to emphasize the dominant 7th and tonic chords in each key. The idea is to raise the 7th scale degree (3rd of the V7 chord) and lower the 4th scale degree (7th of the V7 chord). The tonic chord must have a stable root and the third should be slightly higher in pitch in order to lead to the fourth scale degree. This example is in C major. Arrows are used to indicate how to shade the pitches. Like scales, this exercise improves the flexibility in making adjustments. A good example of the pitch flexibility required in this exercise is in the treatment of B natural in C major and C flat in G flat major. As the leading tone in C major, B is raised and as the fourth in G flat major, C flat is lowered.

It is also helpful to practice long tones with a tuner. This should enhance stability of pitch at different dynamic levels and during crescendos and decrescendos. Of course this practice is meant to help the player recognize discrepancies in pitch and does not replace careful listening.

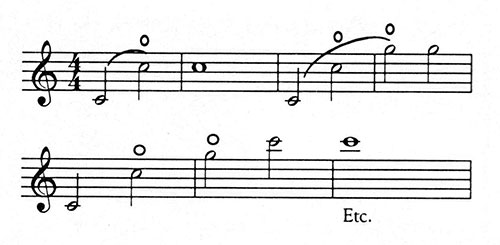

Harmonics can be useful in practicing intonation and they benefit other aspects of playing such as flexibility and sound. Example #2, which is an example using harmonics, can be practiced using low notes such as C, C#, D, and E, etc. In the example, play low C. Using the same low C fingering, play the first harmonic, which is middle C.

Next play the middle C fingering and try to match the pitch. Continue on up through the rest of the overtone series with the low C fingering.

Another exercise using harmonics is to play G harmonic (on the space above the top line of the staff) while using the low C fingering. Change the G fingering while trying to match the pitches. Repeat this once and then move up chromatically to high C# (fingering low C# while sounding G# then play D to sound in A, etc.) I also recommend the harmonics exercises in the Trevor Wye Book 1 (Tone) on pages 6 and 37.

It is also beneficial to practice "difference tones" for intonation, which can be helpful when playing with other wind players. I refer the reader to an excellent article entitled "Woodwind Intonation" by John Barcellona in the September 1998 edition of Flute Talk. Mr. Barcellona explains that when two notes are "played simultaneously by two instruments" a third note is produced. This note is the resultant tone (or difference tone) which is produced at the number of cycles per second that is the difference of the two frequencies being played. The Barcellona article has a chart which lists whether each interval should be played narrow or wide when trying to produce the difference tone. These intervals can be practiced by setting your tuner on one note and playing various intervals or by playing intervals with another wind player. On page 14 in the Trevor Wye practice Book #4 (Intonation and Vibrato) three tunes are written for two treble instruments with the resultant difference tone notated.

Another way to improve intonation is to rehearse and perform with a pianist. Playing with piano is helpful for many reasons; the player hears the work as the composer intended with accompaniment ( thus hearing the chords), and the flutist must adjust to play in tune with the piano. The piano is tuned to equal temperament, which means the octave is divided into twelve equal parts, making each exactly one-half-step equidistant. The flutist must listen carefully to the piano and make adjustments for pitch. Refer to the discussion in Practice Book #4 by Trevor Wye. Mr. Wye’s explanation on working with a piano (pages 6-8) in order to be more sensitized to the overtones is very helpful. I advise any young flutist to begin performing with piano as soon as they are able to. The students’ progress will be faster and more rewarding.

Playing chamber music also sharpens the performers listening skills. You must be familiar with the other parts. All ensemble considerations, such as tempo, dynamics, balance and blend, are the responsibility of the players. Each member of an ensemble must be flexible with pitch. When there are disagreements in pitch, it is helpful to isolate the chord in question and tune it. The way to do this is for the players with the root of the chord to tune this note. Next, add those players with the fifth. When the fifth is in tune the players with the third should find where to place their note (in major chords with winds a low third is desirable). Chamber music rehearsals are more efficient if someone brings a tuner and a score of the works being rehearsed. When using the tuner to correct intonation, have someone else check the tuner when you play your note so that you do not automatically change the note when you see whether it is tending sharp or flat. Remember, the tuner is used only as a guide to achieve the ultimate result of playing in tune with the ensemble. Be aware of the other person with whom you are playing and of your role in the entire mix. Sometimes we have the important line (or melody). Other times we share it with others or we have a counter melody or accompaniment. This is a life-long task. In orchestral playing, when a pitch discrepancy occurs it is a common practice to work out the intonation with the other player or players.

Each person should decide which of these methods of improving intonation are most helpful for their needs. You will enjoy your music making more as you become more successful with intonation.