I set up a chamber music program in my school to introduce students to the idea of small ensembles, to teach chamber music performance skills and repertoire, to relate those skills to large ensemble performance, and to improve student independence on their instruments. My students have become so proud of their chamber music groups that they have created names for themselves. Octotette was one of the names selected by a group of middle school students who were chosen to play in a double string quartet, and that name has become a trademark of the entire program.

I set up a chamber music program in my school to introduce students to the idea of small ensembles, to teach chamber music performance skills and repertoire, to relate those skills to large ensemble performance, and to improve student independence on their instruments. My students have become so proud of their chamber music groups that they have created names for themselves. Octotette was one of the names selected by a group of middle school students who were chosen to play in a double string quartet, and that name has become a trademark of the entire program.

Assembling Ensembles

The simplest way to build a chamber music program is to incorporate chamber music ensembles into the existing lesson program. Put together groups of similar ability levels first, starting with the most advanced musicians, and create the purest type of chamber ensemble, such as a string quartet, woodwind quintet, brass quintet, or piano trio.

The two dilemmas of forming chamber music groups are how to best group students of like ability and which types of chamber ensembles will give the program sustainability and growth. Every music program should have a progression of skill development, or a feeder program, to remain strong, and chamber music is the same. Younger, less advanced students can be placed in two-on-a-part groups or instrumental choirs so they build basic skills associated with chamber music. These can include flute choir, clarinet choir, double string quartet, brass ensemble, and percussion ensemble, or trios with doubled or even tripled parts. As students improve they should move to standard chamber ensembles.

While teaching in Viroqua, Wisconsin I had two strong violinists, a star cellist, and two strong double bass players, all high school students. I also had two high school viola players who were intelligent and up for a challenge, but did not have the facility or knowledge of their instrument as compared to the others. I decided to put together a string quartet, offering a significant challenge to one of my violists, a young student who had a great attitude and desire to excel in music. The two double bass players were formed into a bass duet.

The remaining high school orchestra students were intermediate players, and there was one seventh grade violinist who played extremely well for his age and could keep up with the high school students. I assembled a double string quartet using the seventh grade violinist with some students from the high school and put together a second double quartet of some of the more advanced middle school students. The remaining high school violinists were formed into a violin trio with three violinists per part. These were my weaker students, and they could benefit from a strength-in-numbers philosophy to gain facility while we worked on basic skills. In this three-on-a-part trio the three strongest readers were each assigned to different parts so that students who struggled had someone to lean on for support. The final chamber group was a cello quartet. This left me with a small handful of high school students who needed help with basic skills, and these students were placed into lesson groups.

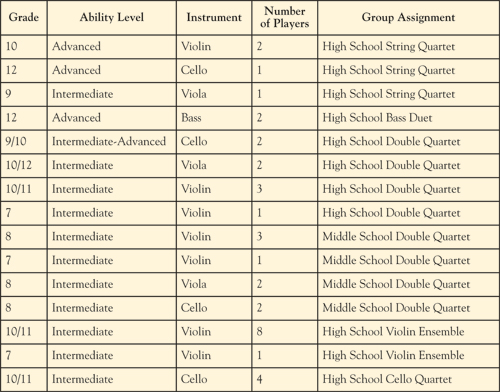

I followed a similar approach with the remaining middle school students, and by the time I finished there were only one or two students who were placed in a private lesson slot until they were able to catch up with other students and merge into another lesson group. The chart below shows how I grouped students into chamber ensembles by ability. The students not included in these charts were placed into like-instrument lesson groups or private lessons.

The most advanced students can perform throughout the school year. Performance ideas include playing a demonstration concert for elementary students, visiting nursing homes or other community facilities, or finding a local café or mall that would welcome a student performance. Scheduling the top chamber groups to perform at these types of venues builds pride in the group and provides motivation for learning their repertoire. Program students to perform their pieces multiple times. With this practice, students will learn how to perform effectively and how to analyze their performances to improve in the future. They will also learn what it takes to really perfect a piece of music, and how to build cohesion as a chamber ensemble. Teach students the basics of performance etiquette including acknowledging the audience’s applause, tuning before a performance, timing between movements, and many other details that are perfect for small group instruction.

Planning for the Year

Once ensembles are formed, plan your goals for each group and a detailed timeline describing sequentially how to accomplish them. List the ensemble skills students should learn. This can include chord tuning, rhythmic interaction between parts, ensemble entrances and releases, melodic and harmonic interaction between parts, sharing and passing of melodic statements, and transitions. Consider which musical skills you want students to develop, such as the keys, meters, and range of the music, as well as the level of technical difficulty. Attention should also be given to musical styles, both what you want students to learn and how this compares to their interests and motivation. This can be a specialized style such as folk songs, music from a specific period or in a specific form, or as basic as legato or staccato. Such decisions will be different depending on the age and level of each ensemble.

I use a curriculum map detailing activities and content month by month for each ensemble. For the long-term success of the program, create a curriculum map that documents several years of educational aims. This curriculum map should document a sequence of assessments for identifiable skills you want them to understand and master by the time they leave your classroom. While scheduling the year, plan monthly goals to help make mid-year and year-end goals easily attainable. Systematically working toward building skills will help students feel successful without pressure or panic as concerts approach.

The concert dates and curriculum map should be coordinated so that your students can showcase their hard work. In my experience, students become extremely proud of their ensemble and want to show everyone what they are playing. Keep in mind that sometimes you will overestimate or underestimate what students can handle. Be ready to adjust if needed so that students will have good performances. In my middle-school double quartet, one of the pieces had a difficult first violin part that required frequent shifting. The first violin players were frustrated and hesitant about performing the piece a week away from the concert. I asked my advanced 7th grade violinist, who had been taking private lessons for years, if he would perform with them. He felt honored to be asked to help, and the other students felt relieved to have a support system in place that would ensure a better performance.

Lesson content should be built with a sequence of skills making sure that you are covering rhythm, ensemble skills, and learning the repertoire at every lesson. Students are likely to need work on unified entrances, articulations and releases, so exercises should be built around these concepts.

Be sure to regularly review your the progress of each ensemble as compared to the previously written short- and long-term goals for each group, as well as the entire chamber music program. As students are learning the concepts selected, make sure that there is adequate time to prepare for concerts and enough opportunities to perform to challenge the group. One thing to evaluate periodically is whether the number and types of ensembles will fit the program for many years or should be changed.

.jpg)

Rhythm skills will make or break a young chamber ensemble playing without a conductor, so build rhythmic content into lessons frequently. Have students play exercises that keep them both rhythmically together as well as independent of one another.

Finding Appropriate Repertoire

The next step is to select literature that fits the curriculum. Choose an appropriately difficult piece that would be an ideal culminating work for the ensemble, something that students can play and that contains skills and attributes that fit your long-term goals for the group. Then, select simpler repertoire to be performed earlier in the year; these works can be used as a stepping stone for learning the more difficult piece down the road.

I consider whether a piece will expand students’ understanding of their instrument. When choosing repertoire, there are a number of factors to keep in mind, many of which have to do with what they should be learning next. This can be new rhythms or keys, modulations and accidentals, form, style, genre, or historical period.

Balance is important when selecting an entire year’s worth of repertoire. I make a chart, noting each of these items as row headers, and concert dates as column headers. With this type of organization, it is easy to come up with a balanced set of repertoire for your ensembles. Keep records from previous years, and document concert repertoire on the school website as a past repertoire page; this will make it easy to review a longer history of each ensemble.

Student response is also worth considering. When students are working on high-quality repertoire, there is much more motivation to learn their parts. I look at whether the main theme is singable and if students enjoy learning that piece. Also, if it would take students more than about two months to learn a piece, find something a little easier; if it can be learned in less than one month, find something more difficult.

Building Pride and Enthusiasm

Help the students build a sense of pride in their ensemble. Encourage them to choose a name for their group. Students may be more excited about choosing a name as they approach their first performance, since by then they would have had time to build relationships with each other. At performances, showcase how special these groups are. This can be done by purchasing corsages for the advanced ensembles so that each group is wearing the same color, or by having students wear something of the same color in addition to their concert attire, such as a red scarf, tie, or hair ribbon. Some students may want to get matching t-shirts. Natural enthusiasm from students can help grow the program; students will talk with their friends, and the reputation of the program will improve resulting in better recruiting and retention and long-term success.

Benefits to Large Ensembles

I started to see wonderful results, particularly in my high school orchestra, between my principal violinist and principal cellist. They started using their chamber music communication skills during full orchestra rehearsal to unite the violin and cello sections. The two students looked at each other regularly, using their body language to portray the exact entrances and releases of phrases, and interact musically with each another within the context of what I was conducting. This was most evident during slower, lyrical and rubato style pieces, but they even used these skills during fast pieces to tighten the transitions.

Students who study chamber music learn how to interact through artistic body language to portray their intentions for entrances, phrases, releases, dynamics, musical shape, and so much more. In addition, they learn how the leading lines pass from player to player, and how that dictates who is in charge of leading the expressive content for the ensemble. When section leaders or principal players figure this out, they will be able to use those same skills to lead their sections and communicate musical ideas to each other, thereby bridging sectional communication. This will result in greater unity of musical expression, cleaner transitions, and most importantly greater enjoyment by students as they become more responsible for musical direction and feel freer to be creative.

The viola player in my advanced string quartet worked hard all year to keep up with the rest of the group. By the end of the year, she made significant improvement to her sound, her knowledge of the instrument, and her ability to play in tune with the group. Most importantly, she developed a love for her instrument and true enjoyment for chamber music; traits that, at best, might have taken much longer to develop had she not taken on the challenge of playing in this string quartet. The other players gave her wonderful encouragement, and the four of them became good friends. They finished the year performing at the school’s orchestra concert, wearing their concert black attire, but with red-rose corsages to complete their ensemble (at their request), and tremendous pride for what they accomplished over the school year. It proves that chamber music can be a very powerful motivator for students. Because of its small group structure, students become more intimately involved with the other students in the group, the music, and their enjoyment for their instruments. The more they learn and enjoy what they are learning, the more likely they are to stick with it and succeed.

All photos for this article were taken by Theresa M. Smerud.

Chamber Music Websites

www.acmp.net

www.chambermusicsociety.org

www.findchambermusic.com

www.musicaviva.com

www.nyssma.org

www.sounz.org.nz

www.wsmamusic.org