There are several simple lessons band directors can teach their flute sections in the areas of tone quality, technique, and intonation that produce measurable improvement quickly. These tips work well with beginning flutists as well as those in middle schools and high schools.

Directors often lament that the flute section is extremely sharp and shrill in the high register or that flutists go flat on diminuendos. Perhaps your flute section has a breathy sound. These concerns and others can be remedied.

1. Improving that First Sound

When teaching beginners to get that first sound, use the headjoint only. This allows them to experience success without the awkwardness of holding the entire flute. Many important skills can be developed using the headjoint, such as tonguing and blowing with a strong air stream. Fun activities with the head joint include exploring the variety of sounds that can be produced, like making glissandos and covering the open end with the palm to produce a low pitch. With the headjoint alone, students can also play several scalewise pitches by inserting the right index finger into the open end of the headjoint. This technique makes three-note songs, such as “Hot Cross Buns” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” possible.

Lip Plate Placement

For good tone, the embouchure plate (or lip plate) should be placed just below the flare of the lower lip, covering approximately 1⁄4 to 1⁄3 of the tone hole with the lower lip. Players should be able to feel the edge of the tone hole under their lip. This position enables flexibility of the lower lip, which controls the angle of the air stream. Students with full lips having difficulty with sound production can place the lip plate slightly higher directly on the lower lip. Traditional methods of placement, such as “kissing” the tone hole and then rolling, tend to place the lip plate too high for most players.

Air Speed

A consistently strong, fast air stream on all notes, both low and high, is necessary for a good sound. I like to use the analogy of using birthday candles – the speed of air must be fast enough to blow out birthday candles.

Forward Tonguing

Teaching students to tongue as if spitting a grain of rice is an articulation method that helps students blow a strong air stream through a small aperture. This type of tonguing produces tone that is strong and full without the usual airy sound that results from an air stream that is too wide. This method of tonguing is sometimes called spit rice tonguing, Suzuki tonguing, forward tonguing, or French tonguing. Sometimes it’s helpful for students to think about touching the tip of their tongue to the top lip to start each note. When they are successful, a small pop sounds as the air is released.

Students with Braces

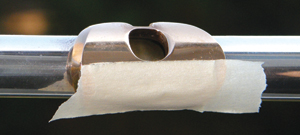

Most students figure out ways to adjust to braces, but those who have difficulties getting a sound might try flute pedagogue Patricia George’s method. She recommends putting layers of masking tape on the part of the lip plate that rests against the chin. This builds up layers of tape to compensate for the changed blowing angle caused by the dental hardware. Two layers of masking tape might help some students, while it may take up to six or more for other students.

After the number of necessary layers is determined, trim the masking tape neatly to the shape of the lip plate.

After the number of necessary layers is determined, trim the masking tape neatly to the shape of the lip plate.

2. Second Octave Notes

Producing notes in the second octave is sometimes difficult for beginners. Because most of the first and second octave notes have the same fingering, the second octave is produced by changing the angle of the air stream with their lower lip. Have students start the high note with the syllable pooh, as in Winnie the Pooh. This may cause some giggles, but that’s part of the fun, and the silliness helps players remember how to start high notes. Pooh pushes the lower lip forward, raising the angle of the air stream, which is then directed across the tone hole rather than down into it. Remind students to use strong “birthday candle” air, which they should already be using on low notes.

3. Right Hand Position

Arched Fingers

Not all hands are the same shape and size, so it is important to teach a hand position that maintains the natural shape of the hand as much as possible. Right-hand fingers should be arched in a position that is natural to the shape of the hand, so that the pads of the fingers are on the keys, not the tips. This natural position allow the fingers to move freely as they change from note to note.

Using the Right Thumb

The right thumb does not need to be under the flute tube. Yes, you read that correctly: The right thumb does not help hold up the flute. It serves as an anchor for the fingers and a point for balancing the flute. Flutist and Oberlin flute professor Michel Debost describes this hand position as pulling a book off the shelf with the book laying sideways.

Many students tend to play with the right thumb too far forward, which cramps their fingers and hinders their technical facility on fast notes.

Many students tend to play with the right thumb too far forward, which cramps their fingers and hinders their technical facility on fast notes.

To find the optimum hand position for each individual, ask students to stand with their right arm relaxed and hanging down at their sides. Without changing the shape of their hand, have them lift and rotate the right forearm until it is parallel to the ground with the back of the hand facing the ceiling. Place the ring, middle, and index fingers on the last three keys of the flute’s center joint, and bring the thumb up to the flute while maintaining the arch of the fingers. In most cases, the thumb will fit into the side of the tube rather than under it. This is good and should be encouraged (see #4 below), because the right thumb does not help hold up the flute.

To find the optimum hand position for each individual, ask students to stand with their right arm relaxed and hanging down at their sides. Without changing the shape of their hand, have them lift and rotate the right forearm until it is parallel to the ground with the back of the hand facing the ceiling. Place the ring, middle, and index fingers on the last three keys of the flute’s center joint, and bring the thumb up to the flute while maintaining the arch of the fingers. In most cases, the thumb will fit into the side of the tube rather than under it. This is good and should be encouraged (see #4 below), because the right thumb does not help hold up the flute.

Lateral Position of Right Thumb

Laterally, the right thumb goes on the back of the tube under the index or middle finger or somewhere in between, depending on the shape of the student’s hand.

To determine lateral placement, have students pick up a soda can with their right hand, as if they were going to take a drink, and check the position of the thumb relative to the index and middle fingers. The lateral position of the thumb on a soda can is the most ergonomically correct for the shape of the hand on the flute.

Encourage players to keep the thumb as straight as possible (not bent at the joint) and discourage hitchhiker’s thumb, where the thumb is stretched to the left of the fingers along the tube.

4. Balancing the Flute

4. Balancing the Flute

Rather than teaching students how to hold the flute, Patricia George advocates teaching them how to balance the flute. The most important support and balance point is the left-hand index finger, which holds the flute up and pushes toward the flutist’s chin. The right thumb helps balance and stabilize the flute by pushing it gently away from the player and counterbalancing the left index finger (when positioned on the back side of the tube rather than under it). This counterbalance stabilizes the flute so that it doesn’t roll toward the player when lifting the thumb key for notes such as C.

Band method books often introduce C5 and D5 as two of the first notes that students learn. However, those fingerings require switching from using just two fingers (C) to using almost all the rest of the fingers (D) – a very awkward motion for beginners. When the flute is well balanced, the tendency for it to roll in when switching from D to C will be avoided.

5. Music Stands

Because the flute playing position is asymmetrical, reading music on a music stand requires a different setup position than that for clarinets or trumpets. When possible, each flutist should have a music stand, as well as ample lateral space between chairs. Players should face the stand and then turn their body and/or their chair 45° (1⁄4 turn) to the right. Their body should remain properly aligned with shoulders above hips rather than twisting at the waist. If they were to lift their left elbow, it would be pointing directly at the music stand.

6. Teaching Correct Fingerings

There are several fingerings that are frequently fingered incorrectly. Most common is second-octave D and E flat – the left index finger should be lifted. According to George, it helps to think of the left index finger as an octave key. These notes have a muffled sound when the finger is not lifted.

Fingerings for third-octave notes can also be a problem because students soon discover that they can overblow the lower-octave fingerings to produce a third-octave note. The overblown version of the note suffers in tone quality and intonation and should be corrected.

Correct fingerings for the high octave are produced by venting at least one tone hole from the second octave fingering. Learning the similarities and differences between the two fingerings helps students remember the fingerings more easily. Band directors should periodically check on the following third-octave fingerings:

D – right hand fingers are off, and the right pinky is down

E flat – all fingers are down

E – left-hand 3rd finger is lifted

F – left-hand 2nd finger is lifted

Students should also learn correct trill fingerings, some of which are intuitive, but many that are not. Easy-to-read trill charts are available free on the internet: www.fluteinfo.com/Fingering_chart/Trill/index.html and educators.conn-selmer.com/woodwind/.

7. Playing Dynamics

When flutists try to play softer by blowing less, the pitch becomes flat. To change dynamics without affecting intonation, players must change the air stream angle while maintaining a consistently strong and fast air. For soft dynamics, the lower lip moves forward, even with the upper lip, so that the air stream is blown across the tone hole. Less of the air goes into the tone hole, resulting in the softer sound. Because the air stream speed is the same as for other dynamics, the pitch is not affected. To start a note softly, use the syllable pooh with a strong air stream. Conversely, for loud dynamics, the lower lip moves back, so that more air is directed down into the tone hole.

For crescendos, the student starts with a pooh attack with lower lip forward and gradually pulls the lower lip farther back to lower the angle of air while maintaining the same speed air stream. For diminuendos, the lower lip starts back so that the air is directed more of downward angle and gradually is pushed forward to raise the air stream angle.

8. Tuning Effectively

Tuning Notes

Before adjusting the headjoint position, try several different tuning notes. Because low notes tend to be flat and high notes sharp on many flutes, students should tune notes in various octaves for an accurate reading of the overall intonation. I suggest using a tuner with D5 as well as A4 and A5. Because more keys are closed on D than on B flat, D is a more stable note. The pitch of B flat is too easy for students to alter with slight changes in blowing angle.

When students play with a strong and consistent airstream, the overall intonation of most flutes is best with the head joint pulled out 1⁄4". Many students fail to pull their headjoints out far enough, which results in an extremely sharp high register.

After tuning the flute, mark it with a fine point permanent marker to help students position the headjoint consistently. Matching marks can also be made on the headjoint and receiver for proper alignment of the center of the embouchure hole with the center of the first key.

For the best intonation, stress the importance of pulling out and aligning the headjoint consistently, even when practicing or playing alone.

Checking Head Cork Position

At the beginning of the school year and on a periodic basis, it is a good idea to show students how to check the cork position in the closed end of the headjoint. This is done by inserting the flat end of the tuning/cleaning rod into the open of the head. There is a line inscribed on the tuning rod approximately 17mm from the open end; this line should be in the exact center of the embouchure hole. The scale of the flute is affected when the line is not in the correct position, causing some of the notes to be out of tune.

When the line is higher than the center, show students how to lower the cork by unscrewing the crown one or two turns and pushing on it until the cork moves and crown snaps back into place. When the line is lower than the center, students can push the cork to a slightly higher position with the flat end of the tuning rod. Check the new position of the line on the rod and repeat as necessary.

Sometimes corks refuse to move and may have been sealed in place with wax. In that case, consult a flute repair technician. The same is true when a cork moves too easily; it may have shrunk due to age and will need to be replaced.

9. Intonation on Individual Notes

After carefully tuning a flute, as in #8 above, students should learn that there are other methods of adjusting pitch besides pulling out or pushing in the headjoint.

Airstream Speed

Slower air speeds lower the pitch, and faster air speeds raise it. Students should learn to play with a strong, consistent air speed and avoid the natural tendency to blow harder or less. Blowing softer for low notes makes them flat and listless, and blowing harder for high notes makes them sharp and shrill. Teaching students to blow at a more consistent speed helps them play better in tune throughout the range of the flute.

Embouchure Hole Coverage

For a good tone, the lower lip should cover 1⁄4 to 1⁄3 of the embouchure hole. Covering too much lowers the pitch, while covering too little raises it. Students with flat muffled tones tend to cover too much of the tone hole, while students playing with sharp, bright, unfocused tone tend to cover too little. The keys of the flute should be parallel to the floor in order to develop consistency in the set up of the embouchure and tone hole coverage.

Airstream Angle

Lowering the angle of the airstream lowers the pitch, and a higher air-stream angle raises it. Flute students should understand that the angle of the air stream affects intonation, as well as the octave. As in octave placement, the lower lip controls the angle of the airstream: when the lower lip pushes forward, the angle of the airstream raises, as does the pitch.

To flatten the pitch players can also lower the chin slightly, and conversely, raise the chin a bit to raise the pitch. These two methods are preferable to rolling the flute in or out, which affects the tone quality.

Posture

Good posture is an essential component of good intonation. Bending or twisting at the waist disrupts the airflow, causing pitch to go flat. Also, the chin should remain level with the eyes looking directly forward. Encourage students to adjust the height of their music stands for good posture and to sit near the front of the chair; this eliminates the temptation to drape the right arm over the chair back.

10. 3rd Octave Alternate Fingerings

There are several useful alternate fingerings for high register notes that help bring the pitch down. They are easy to remember because they are so similar to the primary fingering.

High E: omit the right pinky

High F: add right ring finger

High F#: use middle right finger, instead of ring finger

High A flat: add right middle and ring fingers, which also reduces the note’s resistance. It is also the primary fingering on piccolo.

tudents in both tactile and optic models. The appliqué is easy to install and helps students to find the correct touch points for notes on a 4/4 violin or 14” viola. For more information go to www.daddario.com.