Chicago native Susan Levitin began her flute studies with Ralph Johnson and went on to study with Joseph Mariano and William Kincaid. Levitin received the Bachelor of Music degree with a Performer’s Certificate in Flute from the Eastman School of Music. While at Eastman, she was the principal flute and featured soloist with the Eastman Philharmonia, principal flute in the Eastman Wind Ensemble, and second flute with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

When did you begin studying music?

My aunt was a well-known piano teacher in Chicago, and she started me on piano before I started school. I do not even remember learning how to read music. My father was a serious amateur pianist, and I had piano lessons all the way through my second year at Eastman. I auditioned for Eastman on both flute and piano.

When I was eleven, my parents sent me to the National Music Camp at Interlochen, Michigan. I played piano, but they wanted me to start another instrument. I was assigned to alto sax. When I wrote home asking for money for reeds, I received a flute by return mail and money for private lessons.

As a young musician in Chicago I was fortunate to have a teacher in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), Ralph Johnson. When I was in high school, he arranged for me to join the Chicago Civic Orchestra, the training orchestra for the CSO. There were two rehearsals plus a three-hour sectional each week. Ralph Johnson also arranged for me to have a Civic Orchestra scholarship for two lessons a week with him. He worked with me on orchestral flute parts from the library of the CSO. When I was in high school, I also was in the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra and the Roosevelt University Orchestra.

My parents had weekly series tickets to the CSO. I went with them and sat up in the gallery. My father wired our apartment with speakers in every room, and when he came home from work, he decided what the evening listening menu of classical music was. In this way, I was exposed to a great deal of the orchestral repertoire. I encourage my students to listen daily to classical music. Listening makes it possible to play in the correct style.

When I returned to Chicago after graduation from Eastman, I was fortunate to have close connections with the conductor of the Civic Orchestra, John Weicher, who was also concertmaster and contractor for the CSO at that time. During my years at Eastman, he had me come to Chicago for the occasional week to play extra with the CSO. I also had the support of my piano teacher, Gavin Williamson, who gave me a room in his house to use as a studio to start my teaching career.

What was Joseph Mariano’s teaching style?

Mariano allowed me to find my musical voice. I learned a lot by watching him play. He uncovered the aperture greatly and that gave him his huge projecting sound. His cheeks were always relaxed, and I think he filled all the oral cavities with air. He rarely gave specific comments. Often, he said to fill the room with your sound and to fill the space between the notes with sound. He talked about color a lot. I often played Syrinx by Debussy at the start of a lesson. Some days he said to make it purple or blue or to sound like a cello or a mezzo soprano. He often told me to practice less and to enjoy life more. After each lesson, I spent an hour taking notes on it. Those notebooks are still very valuable to me. In them, I also wrote down challenging passages so that I could review those measures in my daily practice.

One summer I studied with William Kincaid at Mariano’s suggestion. I went up to Little Sebago, Maine, where Kincaid taught around six students. The students rented rooms in a nearby farmhouse, and a local teenager took us across the lake by motorboat to Kincaid’s home on a peninsula. Kincaid taught two of us each day, and we each had two lessons a week.

Swimsuits for teacher and student were typical attire for a lesson, because after a two-hour lesson, he insisted that each of us master water skiing. We spent hours going up and down the lake on skis with Kincaid guiding the boat. His flute lessons were as specific as Mariano’s were nonspecific. We had to memorize the entire lesson, including etudes, and had to be able to transpose the etudes from memory. That kept us practicing for ten hours a day. We had to play repertoire exactly as he did. He had precise ideas on phrasing and where to lead the phrases and why. Those ideas I use to this day with my students. When I returned to Eastman after the summer with Kincaid, Mariano told me never to play the Griffes Poem again because I was just cloning Kincaid’s ideas.

I also spent a summer at Pierre Monteux’s School for Conducting in Hancock, Maine. The orchestra was a tool for training conductors. We had some talented young conductors there such as Erich Kunzel who went on to conduct the Boston Pops Orchestra. I was able to learn a lot of orchestral repertoire playing principal flute there.

Recital in 1962

You had an incredible experience at Eastman. What was the Philharmonia tour like?

During my senior year at Eastman in 1961-1962, the Eastman Philharmonia undertook a U.S. State Department-sponsored tour of Europe, the Near East, and Soviet Union. On this tour, we played five concerts per week for three-and-a-half-months. It was an amazing opportunity. As principal flute I had the opportunity to play the Kent Kennan Night Soliloquy at every concert as an encore, and later I recorded it with the orchestra for Mercury Records. Frederick Fennell coached me on the piece before the tour, and I benefited from his help and from the multiple performance opportunities. On that tour I was exposed to European culture and developed a taste for travel, which I have had ever since.

What did you do after graduation?

When I returned to Chicago after Eastman, I contacted the members of my former woodwind quintet. They needed a flutist, so I performed school concerts with them on a regular basis for several years, learning the woodwind quintet repertoire. The quintet clarinetist introduced me to a contractor for the Lyric Opera, and that led to work at Lyric Opera for three decades doing all the on-stage and off-stage parts. My former piano teacher offered me a studio in his house, and so I began to teach there as well as at Roosevelt University.

Shortly after returning to Chicago, my former piano teacher introduced me to Gerald Rizzer, his former piano pupil. Gerry and I began to work together and founded a chamber group called Shir consisting of four singers, flute, and piano dedicated to the performance of Jewish art music. It was a successful collaboration, and after several years it led to the formation in 1976 of The Chicago Ensemble, a general mixed chamber group. I was a founding member of that group. We performed chamber music with various combinations of strings, woodwinds and voices, presenting unique programs of standard and lesser-known chamber works as well as newly composed music. The Chicago Ensemble presented a concert series in three locations and performed live radio broadcasts. We were one of the first groups to perform George Crumb’s Voice of the Whale. For many years we were the only group in Chicago that presented such varied and adventurous programs. Then other mixed chamber groups in the area followed our lead.

Gerald Rizzer and I collaborated for many decades with The Chicago Ensemble and also performing flute/piano recitals including some for WFMT, the classical music radio station. We recorded two CDs together of some of the music we had performed. The first CD was La flûte lumineuse, and the second was American Duos for Flute and Piano.

The Chicago Ensemble

What were some highlights of your teaching career?

I spent several decades working at the Sherwood Conservatory of Music as Artist Faculty. During those years I founded the Festival of Flutes with Diane Willis and directed the Festival for a decade. We had a full day of adjudicated flute and chamber music performances for about 250 students followed by an Honors recital. I also founded and for many years directed the Sherwood Flute Institute, an intensive two-week summer flute program with four to five faculty members and 20-25 students. In addition, I co-directed a two-week summer High School Chamber Music Institute that had numerous small mixed chamber ensembles.

I have been very fortunate to have taught some extremely talented and motivated students. My students have been represented in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Minnesota Orchestra, the Seattle Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Metro-politan Opera Orchestra, Richmond Symphony, Spoleto Festival, Auckland Symphony, and San Diego Symphony to name a few. Some of my better-known students are Demarre McGill, Emma Gerstein, Mary Boodell, Barbara Leibundguth, Hideko Amano, Holly Hudak, Rachel Blumen-thal, Alison Brady, as well as numerous fine flute teachers in the Chicago area.

I have always encouraged cooperation rather than competition between my students. It is the job of the student to reach for the best in oneself. Each year I coach at least one chamber group, often a flute trio or quartet. Ensembles create a bonding within my class as well. I also use ensembles as an opportunity to teach students how to study a score and use the score to put helpful cues into their parts.

How do you help students prepare for music school and auditions?

Each year I work with several students who are auditioning for music schools, as well as students auditioning for concerto competitions and orchestra chairs. For college auditions, the student starts on the repertoire at least a year before the audition and memorizes all of the repertoire. There are numerous collaborations with the accompanist to understand the total work. Usually, a Mozart Concerto is included and a French competition piece, as well as standard orchestral excerpts. Many schools now require a pre-audition video. For this we go to a professional recording studio. I encourage my students to give a full recital of the repertoire before the auditions.

With Demarre McGill

What do you focus on in your teaching?

Teaching is about problem solving. It is also about establishing a relationship with each student. I focus on the individual issues of each student celebrating his or her strengths and addressing challenges. Working with students has helped me to understand my own playing better and allowed me to articulate solutions to musical and technical problems. I have had students with physical challenges, learning disabilities, and psychological issues. Early on I had a wonderful student who was completely blind. Currently, I have a student who has finger dystonia and other hand issues. I have also had a student who had dystonia of his embouchure. Addressing these issues has been challenging and demanded creative solutions. I emphasize artistry in my teaching, but to get to that level, there are three non-negotiable factors: accuracy of notes, rhythm and pitch.

Accuracy

At all levels, I use subdividing as a tool for absolute rhythmic accuracy. I have students tongue all subdivisions until the rhythm is absolutely clear. In addition, using the metronome is important to achieve steadiness of tempo. To learn difficult note passages accurately without rushing, I have students use tremolando on each note of the challenging passage. It allows them to play slowly and accurately.

Most of my students are adults or young adults, but I do have a couple of beginners. Before I take a new student, we have a trial lesson to see if we are a good match. With beginning students, I use a rug with appliqued feet for accurate foot placement. Students can make their own foot placement rug with a bathroom mat and a magic marker. I use the photos in Angelita Floyd’s book on Geoffrey Gilbert to demonstrate correct body stance.

Tone Development, Tuning, and Phrasing:

Following the example of Joseph Mariano, I encourage students to uncover the aperture and to separate their teeth to get a larger resonating chamber as well as pulling the top lip close to the aperture. For soft attacks and low notes, I recommend touching the tip of the tongue to the top lip. An open holed flute encourages students to have much better hand position. Arms should stay away from the body to allow the ribs to expand with the breaths. To improve breath capacity and efficiency, I use breathing tools such as the breathing bag and Voldyne that the late Arnold Jacobs used in his breathing studio.

Most of my students work daily in Moyse Tone Development Through Interpretation and De la Sonorité. I emphasize memorization and transposition. A lot of tone development and accurate pitch can result from transposing these studies and playing them from memory while watching the tuner. Since they are vocal excerpts, these studies encourage the student to sing the tone.

I encourage students to make a chart of each pitch on the flute and to write in the pitch tendency of that pitch at three different dynamic levels. This makes for an awareness of the pitch tendencies of the flute.

I also ask students to write in all of the breath marks to develop awareness of where the phrases begin and end. We work on crescendos and diminuendos with the tuner to develop pitch control along with dynamic control. I use brackets in the music with the “Kincaid” phrasing to show where the phrases are going.

Technical Development

All of my beginning students memorize the major scales, arpeggios and chromatic scales by the end of their first year. Along with the memorized scales, I use Anne McGinty’s 99 Irish Dance Tunes for practice reading in every key. I also have students work from Taffanel et Gaubert, 17 Daily Exercises, memorizing number 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 15, 16. I use Geoffrey Gilbert’s Technical Flexibility for 4th octave work and Robert Stillman’s The Flutist’s Detache Book for tonguing etudes. “The Nightingale’s Warmup” from Paula Robison’s Flute Warmups book is excellent for trill studies and finger evenness.

Intermediate students work on Thomas J. Filas Top Register Studies and Leger Domain for facile note reading and Reichert Seven Daily Exercises. They also play short salon pieces such as Pessard’s Andalouse, Godard pieces, Mozart’s Andante in C, and Donjon pieces.

For advanced students one of my favorite etude books is the JeanJean Etudes Modernes. It is excellent for rhythm work, tone colors, and vibrato. In terms of repertoire, I expect all advanced students to have memorized at least the first two movements of a Mozart concerto. Initially, we isolate the more technical measures and work on them as exercises before going to the rest of the concerto. Everyone studies some Bach, a French competition piece, a standard sonata, a 20th century piece, and three or four orchestral excerpts. After that, students can go on to the more technical concertos and competition pieces. Students give a graduation recital at the end of high school.

I have been very fortunate to have a close and supportive extended family. I met my husband during my second year at Eastman, and we had a beautiful marriage of 47½ years. He was a lover of classical music and started oboe at Eastman as a student of Robert Sprenkle. When I had the opportunity to go on the Eastman Philharmonia tour right at the beginning of our marriage, he encouraged me to do so. Later on, my parents were always available to help with our children, which was especially helpful when I was working eight shows a week at the theatre in the stage orchestra for Evita. My mother-in-law retired to Chicago and helped as well. It was always challenging to meet the needs of others as well as my own, but having a close family made it possible. One of my great joys now is teaching my granddaughter Amalia.

What else do you do besides music?

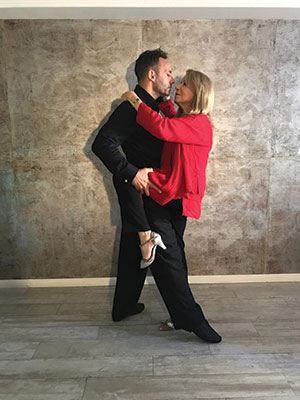

About fifteen years ago I attended a tango show and fell in love with the music. I decided that I had to dance tango and began to take tango and Spanish lessons, which I continue to do. In fact, I go to Argentina every winter for several weeks and at that time teach my students by Skype.