Middle and high school tuba players rarely understand melody and phrasing as well as other students. This is in part because most tuba players switch to tuba after completing at least one class method book on their first instrument. At that point instruction usually involves giving the student a tuba, fingering chart, and music and letting him teach himself. The other students continue to progress through the lesson book while the tuba player starts from the beginning. Other band members play new music that teaches time, rhythm, keys, melody, and form, but the tuba plays the same general outline of root third, and fifth common in bass patterns. This is the nature of some styles, but if tuba players only have these kinds of parts, it is akin to a method book repeating the same lesson numerous times.

Middle and high school tuba players rarely understand melody and phrasing as well as other students. This is in part because most tuba players switch to tuba after completing at least one class method book on their first instrument. At that point instruction usually involves giving the student a tuba, fingering chart, and music and letting him teach himself. The other students continue to progress through the lesson book while the tuba player starts from the beginning. Other band members play new music that teaches time, rhythm, keys, melody, and form, but the tuba plays the same general outline of root third, and fifth common in bass patterns. This is the nature of some styles, but if tuba players only have these kinds of parts, it is akin to a method book repeating the same lesson numerous times.

The first time most tuba students play a melodic piece is at ensemble auditions. These performances may have the right notes or rhythms, but lack phrasing. This is not always because the instrument is cumbersome or the student did not practice enough, but because tuba parts offer little practice for melodic phrasing, form, and development. Changes to warmups and programming can remedy this.

The first thing to focus on is playing and writing scales, especially ones beyond Bb. It will be difficult at first, but the benefits include an expanded range and better reading. I like to teach my high school groups through five flats and five sharps in major and minor keys. I write the scale on the board in each instruments’ key and ask the students to write it down on a piece of staff paper to keep in their folder. As we play, they should only breathe every four bars. This helps the tubas learn to play phrases in one breath.

Too often tubas are relegated to whole and half notes, so I like to use varied rhythms for warm-ups with different scales, and frequently take both from the music the band is rehearsing. The whole note is part of the instrument’s repertoire, but heavily rhythmic warmups will teach tuba students to play eighth-note passages quickly. In common time, play one whole note, two half notes, four quarter notes, eight eighth notes, twelve eighth-note triplets, and sixteen sixteenth notes. This can help rhythmic accuracy and subdivision, something tuba players rarely get an opportunity to practice.

Many directors use chorales in warmups, but it would be beneficial to check the tuba parts. If the music is written with only whole notes and half notes with an occasional quarter note or two, students will not learn much. Look for chorales that give the tuba section melodies or countermelodies. Many of Bach’s chorales have interesting and varied bass lines, and James Swearingen’s chorales also give the tubas some melodies.

Repertoire should have as much variety as the warmup. I look for music that develops and teaches all musicians in the band, but this is sometimes difficult to find for tuba players. Once I have picked a program, I look at all of the tuba parts to see if there is enough variety. My college would bring in a composers to conduct our winter concert, and we would play through 15 or 20 of their pieces before deciding on a program, as the second half of each concert would consist entirely of pieces written and conducted by the guest composer.

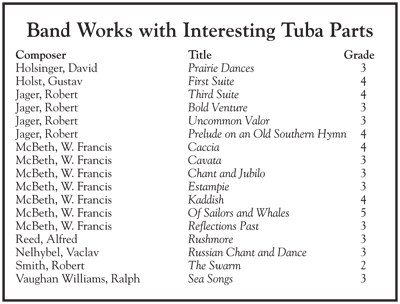

During one of these reading sessions I found that the same rhythm and notes appeared in the tuba parts for six out of the 15 pieces. Even if a program has different composers, the tuba parts often look similar because there are only so many variations of root, third, and fifth. There are plenty of good band works with interesting tuba parts, and most schools are likely to have some gems buried in their libraries. I have found some great pieces and arrangements by composers, including some who are not well known.

There are many good warmup and etude books that can help tuba players. The Rubank books are good for young or new students. They provide not only the scales, but 32 to 48-measure etudes with melodies in different keys, time signatures, and registers. The Blazhevich and Marco Bordogni etudes are great for high school or advanced students. Blazhevich uses various types of articulations and extreme ranges, and Bordogni contains legato etudes that require great flexibility, range, and air control.

The main problem tuba students will have with these etudes is turning the notes on the page into melodic phrases and connecting these to create a unified piece of music. The best place to start is to have them identify the key signature, time signature, and the highest and lowest notes in the piece. Next the student should read the first 16 measures. In this reading they usually do not put the rhythms and notes together into a melodic idea.

After the first read students should identify the first four-measure phrase and the next four measure phrase and how they relate. Then ask how those two phrases connect as an eight-measure phrase and how that relates to the next eight-measure phrase. This helps the student see melodic relationships that are less common in many band parts. Most of their music goes from whole note to whole note, quarter note to quarter-note rest, or uses another simple formula. They generally play the same pitches and rhythms even if the melody changes. That type of music prevents them from seeing long phrases, so when they play an etude or melody they view it as a series of notes with no connection. Teaching them how to recognize phrases and form will help them see where the music starts and how to connect the beginning to the end.

I show how the first note and the last note of the phrase is either the root, third, or fifth of the scale to relate the melody to the harmony they frequently play. Most players also miss the fundamental idea that the highest note in the phrase is what the musical line builds to and resolves from. They get side-tracked by note intervals, rhythms, or extreme ranges. Once they understand these concepts they can play the 16-measure phrase more musically.

Throughout this process, play along with the student regularly. A low brass instrument would be best because a tuba, euphonium, or trombone would also demonstrate a good sound. The next best thing is playing the parts on a piano in the same octave as the tuba. This gives students a better idea of the sound than playing the part on a higher instrument.

With a collection of good tuba music, tuba sections should become more interested, focused, and attentive. The music may seem too difficult at first, but over time the tubas will learn parts more quickly, practice more, and listen. They will see that you value their contribution and will work harder.