The Ictus

In conducting, the ictus is the exact point in each beat of the conducting gesture that indicates the pulse of the music to the ensemble. In foot tapping the ictus is the moment when the foot touches the floor just before its return to the up position. In flute bobbing, the ictus is the exact moment when the end of the flute is no longer going down, but is about to go back up to normal playing position.

Problems

The old saying “You get what you conduct” applies here. Many conductors are not careful in indicating the ictus. It tends to be more prominent in faster, staccato or marcato passages and absent in lyrical passages. If an ictus is not present, players look to someone else to indicate where to play – the concertmaster in an orchestra and the flutist whose part begins the composition or has the prominent line in a flute choir.

Assuming the conductor’s ictus is well-defined, then it is each player’s responsibility to play with it. This means that they should look up at the beginning of the composition and then at least once every measure or two. For flutists with vision problems (bifocals, trifocals, etc.) this can be a problem because when they look up and then back down, it may be difficult to find their place in the music or wait for the music to be in focus. For these cases, some memory work of the music may be required for the sake of good, accurate ensemble playing. Practicing looking up at the conductor each measure or two should be a drill during the warmup part of flute choir and other large ensemble rehearsals. With practice anyone can do it well, but without repeated practice, it will never be conquered.

In classical music, the chord changes are usually on a strong beat. If one group is early on the beat, then their entry clashes with the previous chord. If another group plays late on the ictus, then their note hangs on too long into the next chord. For a brief moment everything might be okay, but overall the approach to the chords is not clean or accurate.

Articulation Issues

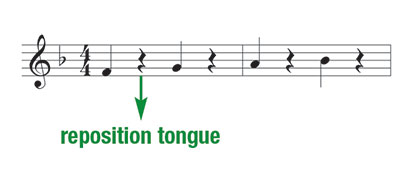

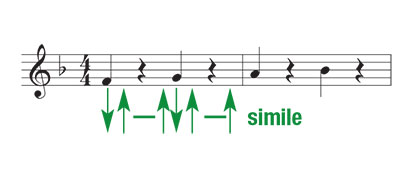

Many flutists cannot play exactly with the ictus because when articulating, the tongue is too far back in the mouth. William Kincaid, the father of the American school of flute playing, suggested putting the tongue in the aperture, letting the air stream build up behind, and releasing the tongue on the conductor’s ictus. He laughingly called this “spit-ccato” tonguing. This is exactly the same type of tonguing as the forward or French (probably more correctly called German) tonguing gesture. (This is taught by having the student spit a grain of rice or a fig seed.) Flutists of all ages and levels of development should practice the following exercise on several scales each day. After the release of the tone, the tongue is replaced in the aperture during the rest to be ready to play the next note exactly on the ictus. Using a metronome with a background of four sixteenths ticking helps the player place the note on the beat.

Where’s the Beat?

Student and amateur flutists often play before the ictus. Seasoned professionals (especially those who have played in orchestras their whole careers) play late on the beat. To win an audition, you must play on the beat. Rhythm is both a talent and a discipline that must understood and practiced.

Pointing the Feet

To become cognizant of where the ictus is, have students sit on the floor with their legs stretched out in front and their toes pointed up. Next, they should take the index fingers of both hands and point them at the ceiling. Then pivot the index fingers towards the feet and as they turn down, quickly point their toes with the feet bending at the ankle. Practice this with the metronome set at q = 72. Most students do this best when the speed is similar to their heart beat. Saying down/up, down/up when doing this helps the less coordinated. Explain that at the moment the toes stop going down and begin coming up is the ictus. Each week work to increase and decrease the tempo from the starting point of 72. I always practice this exercise with students. It is good for me too.

After several weeks, begin the lesson using both feet and then transition into first the left foot only and then the right foot only. Return the metronome to q = 72. The left foot will move on 1-and and the right foot on 2-and. Be sure the movement of the feet is articulate and not mushy. The movement from the ankles should be as clean and as simple as possible as if imitating a modern dancer.

Repeat these exercises until students are comfortable, and the exercise seems simple. Then move on to foot tapping. In many flute studios foot tapping is considered a bad thing. I use it as a step to learning to playing with the ictus. Since children learn coordination from large muscles to smaller muscles, I teach foot tapping using both feet first and with the feet bending at the ankle. This seems like a simple concept, but I have found that many middle school students have difficulty moving at the ankle. You may have to spend some time reteaching the previous exercise to develop this movement. Many students have grown up primarily indoors with little exposure to movement and consequently have weak body awareness. Rectifying this is something to cultivate. Eurhythmic exercises are helpful.

The feet move down on the number part of the beat and up on the and. This motion should be clear and concise. Practice this with a metronome until students are comfortable, and the gesture seems simple. Then explain the concept that the moment the feet touch the floor and begin the ascent is called the ictus, and this is where they should place notes to play in time. Practice this at varying tempos both below and above 72. Point out that when the beat is faster the distance the feet move is shorter. Once there is success, move on to tapping only one foot which will probably be the right foot.

Besides working with a metronome, record a mix of sixteen bars in varying tempos and genres. Have students find the beat and tap (and perhaps clap their hands) to the beat. Work in simple meter first (beat divided by two) and later incorporate compound meter (beat divided by three).

One of my theory professors at Eastman mentioned in passing that we each should feel the beat in some part of our bodies when playing. In the theory sequence, a large amount of time was spent each on rhythmic reading. While doing this, the right hand conducted the beat pattern, the left hand tapped the background (eighths or sixteenths) on our desks, and we counted aloud. As we became proficient, we sang the music with the correct pitches. The important part of this exercise was how many body parts were involved in doing rhythmic reading. Perhaps that is why the Eastman Wind Ensemble recordings with Frederick Fennell are considered to be so fine. The rhythm is impeccable.

Periodically I work with my flute choir on foot tapping. We are always surprised at how difficult it is for everyone to do it exactly at the same time.

Flute Bobbing

After a student is proficient with foot tapping, then teach flute bobbing. Flute bobbing is when a flutist moves the upper body in unison with the end of the flute as if cueing a breath. The gesture is small but very clear. The flute is firmly in the chin, and the weight of the flute may rest more just above the left index knuckle. This gesture is used primarily for cueing; however, it can be used as an aid for getting all of the players in an ensemble playing on the ictus.

Put the metronome on quarter note = 72 and have the flutist move on beats one and three. By removing the movement on beats two and four, the flutist has time to prepare the next gesture. At this point beats two and four will serve as preparatory beats. Practice this in the mirror with you making sure the student’s gesture is the same distance as yours.

I had a flute choir at one time comprised of flutists of a wide variety of levels of playing. As a group we practiced this in the mirror, drill team style, to get everyone moving exactly the same. We all were surprised at how difficult this was. At the point where the flute stops going down and begins going up is the ictus. The goal is to get everyone to play exactly on the ictus. Counting subdivisions is a big help in achieving this.

Playing Off the Beat

Musicians regularly play notes on the beat. Because it is so common, they become sloppy in preparation and note placement. To revisit the preparation needed to play accurately on the beat, at each flute choir rehearsal or private lesson, we always play a few scales where the flutists play only on the off-beats. (In other words, the numbered beats are silent and they play on the ands.) Since this is less familiar, they count more accurately to place the notes correctly. After playing a few scales off the beat, we return to playing scales on the beat. The off-beat counting strategies are easily transferred to playing on the beat. This exercise also heightens rhythmic awareness and may help in reaching the goal of playing exactly on the ictus.

Intonation

When everyone does not play on the ictus, intonation problems occur because the weakest, non-rhythmic players play before the beat. These people become the ones setting intonation. If everyone plays on the ictus, then intonation will be greatly improved.

Long Term

This skill is something that should be practiced regularly. Once you play in an orchestra where there may be a lot of rubato or accelerando, the tendency is to go with the flow. Then the weeks, when there is a conductor who has excellent stick technique, it becomes apparent how sloppy the ensemble has become. Low flute players especially should work on not being late on the ictus because of the slow response of the instruments. A metronome set to subdivisions is a helpful aid. Having good intonation and ensemble playing is the reward for diligent work.