Recently I led a flute choir reading session with a group I had heard perform a few weeks earlier. I had been impressed with their phrasing and musical understanding, so I was surprised to hear them sound like a bunch of intermediate-level players while sightreading. I realized that when faced with unfamiliar music, they had reverted back to playing rhythmically accurate, but bland and musically static. This happens frequently with even quite good players and perhaps has evolved from an approach of “get the notes and rhythm first, and add the musicianship later.”

A few years ago, when working with a new music group, one of the composers said, “New music should have an interpretation, just like music of an earlier age.” Since then, even when I am sightreading, I have tried to approach all music in a way that sounds authoritative and not questioning. On subsequent readings, I can fix what I guessed wrong about. The main goal, however is to try to put character into the notes.

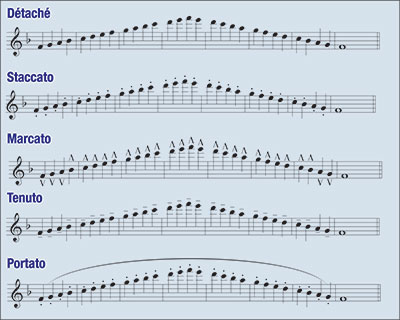

For wind players there are five common performance marks. Identifying them and practicing with them in character will add a new dimension to both sightreading and performance. In all five examples, the beginning of the note is the strongest and is produced by tonguing tu. If played with vibrato, the cycle starts at the beginning of the note. When playing in common time, the first beat is the strongest, followed by the third beat, then second beat and finally the fourth beat. When sightreading, many players omit this strength of the beat rule.

Détaché

To many players this would be called a normal note. It is played separated but not staccato. This is the type of articulation that most players fall back on when playing unfamiliar works.

.jpg)

Staccato

If you ask a student what staccato means, the answer will be to play the note short. That is only part of the answer. Staccato means to play the note detached from the note before and from the note after. The note before will be shortened to clear a space or silence, and the note itself will be shortened to clear a space after the note. Listen carefully that the tongue does not stop the sound at the end of the note. The tongue remains in position and is moved during the silence after the note.

Marcato

A marcato is a super-sized staccato. It is played with more emphasis which translates into using a faster air stream.

Tenuto

The word tenuto comes from the Latin word to hold. While the notes are a bit longer, there is still separation between them.

Portato

Portato means carried. The notes are played similarly to a tenuto but with a bit more direction and a small silence between each note. How much silence depends on the tempo of the piece. The faster the passage, the shorter the notes, and the longer the silence. The opposite is true for slower passages.

Sightreading

When sightreading, most flutists revert to their lowest level of musicianship. A teacher’s goal is to help students become so comfortable with the basic ideas of musicianship that they are not abandoned when sightreading. Have students practice an F major, two-octave scale the following five ways: détaché, staccato, marcato, tenuto, and portato, as shown in the box below.

Record students and during the playback, discuss if the desired articulation mark was executed on each pitch. Then play a game where the teacher plays the scale with one of the articulation marks, and a student identifies which articulation mark was used. Next, switch roles. If time is limited, only play the first five notes of a scale. If the front of a note is chipped, students should listen carefully to notice whether the chip was high or low. If the chip was high, then the air stream needs to be aimed lower. If the chip was low, then the air stream needs to be aimed higher.

Dynamics

When I was a young student reading adjudication remarks, there was always something written about how I needed to do more with the dynamics. I though for a long time that this was a cop-out for the judge. I wanted to know the real insight to playing better. Little did I realize that dynamics were the real insight. I was so focused on developing a big, rich, vibrant tone that I played every note this way. It was like shouting every note to the listener. Recently I heard a conductor say, “The most intimate things that will be said to you in life will be said in a whisper.” That was his plea to get the orchestra to play passages softer when called for. Waiting to put the dynamics in at a later time is not the best idea.

While teachers do want to develop that big, rich, vibrant sound in students, they also should work on getting students to play softly with that big tone. To develop this, students should practice scales with the articulation marks again, only this time create a dynamic design. For example, they could diminuendo to the top note and crescendo to the bottom note. Create several scenarios.

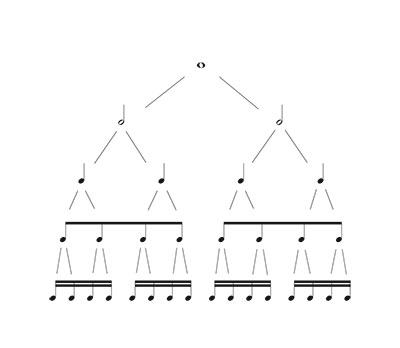

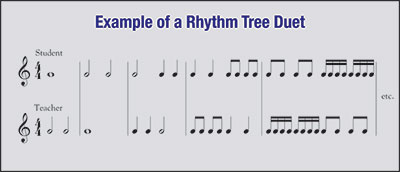

Subdivision

Beginners often learn to count using a rhythm tree. However, once a student understands the basic mathematical symbolism of the tree, it tends to be abandoned – usually too soon. Working the rhythms of the tree in duet form (teacher and student) may enhance their rhythmic sightreading in the future.

Counting Many Similar Notes

When there are many notes of the same value played in succession, many flutists have difficulty perceiving how many notes have been played. Make a game out of counting the notes to help student understand that counting is a constant process. For this game, the teacher plays a measure of varied notes from the rhythmic tree and then immediately following that the student plays back the same notes. This game is excellent for developing aural skills. More advanced flutists can play counted or measured vibratos rather than tonguing the subdivisions.

I was recently coaching the bird movement from Saint-Saens Carnival of the Animals when a flutist turned to me and asked, “Am I tonguing enough notes?” Obviously, she was comfortable playing groups of four sixteenth notes, but playing groups of eight thirty-second notes was something new. Learning to play many notes on one pulse early on will help students sightread with confidence. To practice this, ask students to play the F major scale in quarter notes and decide upon a rhythmic pattern such as quarter on the first note and four sixteenth notes on the second note. Go up and down the scale in this way. Then put two eighths on the first note and four sixteenths on the second note. The number of patterns that can be created is almost endless. Playing these mind games greatly increases students’ understanding that the pulse in music is continuous but they have to put different rhythms on each pulse.

Counting Silently

A student recently remarked that counting in her head was difficult especially when she is playing in a less familiar key, and the rhythms are tricky. The following exercises are useful in helping students count.

Add-A-Beat

With the right hand on the barrel, students play a middle octave B for one quarter note followed by a rest. Then, they add one quarter note of duration to the played note so the next time it is play two beats (a half note) and rest one, then play three and rest one, etc. They proceed without stopping through the pattern. When practicing this with a group, I am always surprised at how ragged the note lengths become. Clearly, counting the long note is a problem. Practice this until students can play up to a 12- or 16-note count and stop at exactly the correct place.

Add-A-Rest

For this exercise students again place the right hand on the barrel and play a middle octave B for a quarter note followed by a rest. However, on each repetition the rest is lengthened by one quarter beat, so the second iteration is a quarter note played followed by two beats of rest, and so forth. Continue until the rest reaches 12 or 16 beats long.

Spending time on counting and listening develops both of these skills that are so necessary in sightreading. The goal is to be able to sightread at the highest performance level. This means that students should learn to sightread with authority and musicianship which help them play with confidence throughout their playing careers.