On Tuesday, May 10, 1994, my classmates and I put down our instruments and walked out of band without permission. This was the day an annular solar eclipse crossed North America in a path from Baja California to Nova Scotia. (An annular solar eclipse occurs when the moon is too far from the earth to entirely block out the sun; at the peak of the eclipse, the moon causes the sun to look like a ring.) My high school was within 60 miles from the path of annularity, scheduled to pass by during our fifth-period rehearsal. I wasn’t the ringleader of the walkout (graduation was two weeks away, and I wanted to preserve my lifetime detention-free streak), but I am fairly certain I was quick to follow those who escaped first.

My fascination with astronomy long predates my discovery of Holst’s The Planets. I was fortunate to grow up in the country and had great nighttime viewing; I loved looking at the Milky Way galaxy and finding the constellations. The final two decades the twentieth century also featured Pluto coming closer to the sun than Neptune (1979-1999), the first up-close photos of Uranus (1986) and Neptune (1989) courtesy of Voyager 2, and the return of Halley’s Comet. Sadly, the comet was on the opposite side of the sun as earth, creating the worst viewing conditions in 2,000 years.

To me, part of the appeal of astronomy lies in how much we don’t know but can still make a good guess at. It is possible that at some point in the past Uranus and Neptune traded places; it is also possible that millions of years from now Jupiter’s immense gravity may yank Mercury out of orbit. Moving further from our solar system, astronomers believe they have found a planet so hot that it rains glass – sideways – and a star so large that, if placed where our sun is, might extend past the orbit of Saturn, which is almost ten times as far from the sun as earth is. The universe offers something for everyone.

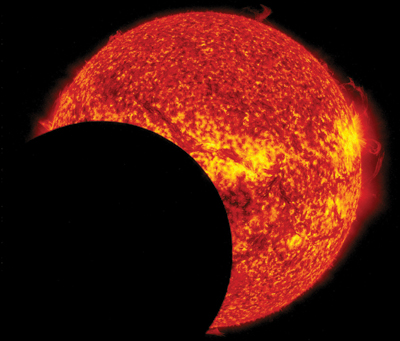

The moon passes in front of the sun as seen from the perspective of NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory in the early morning of Sept 24, 2014.

A couple years ago, I read an interview with several astronomers. The comment that stood out was, “All I do is math.” I cannot imagine the calculations that go into predicting eclipses, plotting flight plans of space probes, or estimating the distances and sizes of the farthest galaxies.

Music is not without its share of mathematics. We all learn that the third of a major chord should be 14 cents flat and a fifth must be played two cents sharp to be in tune. The overtone series that we are used to seeing indicates frequency ratios between intervals, and the twelfth root of two represents the frequency ratio of a semitone in equal temperament. (I also have memories of my Music Theory V textbook looking much more like a math book than the one we used for the first four semesters.)

The mathematics behind both music and astronomy is why these two subjects were part of the ancient Athenian core curriculum, but I am glad I can enjoy performing and listening to music without needing to worry too much about it. Similarly, I can marvel at the night sky or read articles about the Great Attractor without doing any math at all. What makes music and astronomy such wonderful pursuits is that there is so much beauty and wonder available no matter how deep one chooses to go.

I start a semester of voice lessons this month, not with hopes and dreams of making it big as a vocalist, but rather simply to be a better back-up singer in my church’s band. I’m excited to have this opportunity, even if my goals are less serious than those the other studio students might have. One might say a career as a pop sensation isn’t in the stars for me.

Teachers who start school before Labor Day (or those who have marching band camp in August) should note that North America will experience a total solar eclipse on Monday, August 21, 2017, with totality following a path from northwestern Oregon to South Carolina. (The rest of the continent will experience a partial eclipse.) Enjoy it if you are able; I am hoping to escape the office for a day and do likewise. In the meantime, best wishes for a happy new year.

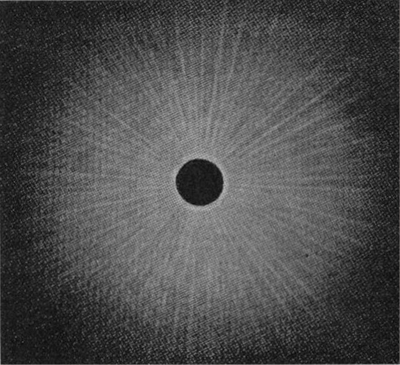

Sketch by Spanish astronomer José Joaquin de Ferrer depicting the solar atmosphere, or corona, during a June 16, 1806, total solar eclipse.