Jazz rehearsals can sometimes seem to have a less organized approach, and the music can be treated as less important than that of other types of ensembles. Often, the groups I have worked with are run in a more casual fashion than concert bands. Some of it is the nature of the music and the view that jazz is less academic, important, or sophisticated, perhaps because it is closer to popular music. Here are some ways to get a student jazz group sounding, looking, and acting like professionals.

Starting Silently

The less the director talks, the less the students will. Teach the band a routine for starting rehearsals on time. Richard Dunscomb suggests that each jazz ensemble rehearsal should begin with an exercise that engages the students musically and sets the tone of priorities for the rehearsal. When the rehearsal is scheduled to begin, play an A on the piano and cue the saxes to begin tuning. The bass and guitar may also want to use this pitch unless they are using electronic tuners independently with their quarter-inch cables. Quickly follow this by cueing the brass with a B-flat. Seconds later, start the warm-up piece. It takes only a few rehearsals for students to realize that if they are not ready to tune and play when you are, they are late.

The purpose of a warm-up chart is to get everybody focused on the rehearsal and get air moving through horns. The best warmup pieces are short-duration, medium-swing charts with easy ranges. Sammy Nestico’s arrangement of “Just in Time” (Stratford) works very well for this exercise because the chart has ample full-ensemble writing in the middle registers of the instruments.

After the warm-up piece tune again if needed, then briefly list a few specific objectives for the rehearsal. By eschewing an electronic tuner directors can not only save time, but also train students to use their ears and tune during the warm-up. A few short announcements might be better saved for the transitions between charts as a means of giving students a few minutes to rest their chops. It is even better to write all announcements on the board. Remember that players at all levels of development come to rehearsal to play, not listen to speeches.

Get People Dancing

Carefully designed rehearsals yield the best bands. The top musical priorities for a jazz ensemble should be style, rhythm, and time. In the past, when musicians were trying to keep gigs in their books and food on their tables, their first priority was to keep the audience dancing. Getting an audience to feel like dancing depends primarily on style, rhythm, and time. Elements such as intonation, harmony, phrasing, and dynamics are important but secondary. In the words of the great Duke Ellington, “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

Great bands and soloists who have had less-than-optimal pitch or tone have become definitive artists in the industry because of their superb style, rhythm, and time. Think of the famous solo Miles Davis played in “So What” on the Kind of Blue album. Many times I have heard a young student play all the correct notes in a transcription of this solo but still deliver a musically unsatisfying rendition. When a piece lacks the correct style, rhythm, and time there will be no emotional response to get anyone moving. The right notes at the wrong time are wrong notes.

Style Struggles

When teaching students how to swing, many times directors will focus on changing that eight-note rhythm to something loosely between a quarter-eighth note triplet and a dotted eighth-sixteenth note, depending on tempo. Too many directors focus on the rhythms but not on the articulations associated with good swing style. The result of this is a band that plays fairly accurate rhythms but sounds hokey because of stylistically wrong articulations. In Latin styles or some types of big-band music, such as an Ellington chart, a short note might be played much shorter and crisper than one with a similar marking but from the Count Basie Orchestra tradition. Articulations depend not only on the style but also on the composer and the practices of the time.

One common mistake in interpreting rhythms incorrectly is overinterpretation of the style. In a chart from the library of Sammy Nestico or Dave Wolpe, which are permutations of the Count Basie style, laying back on the beat, which can be described as a tug and pull between the wind players and the rhythm section, can be difficult to teach a band. The best way to learn to interpret rhythms is to listen to the recordings. I have often heard bands try to mimic the recording but pull back too much; this disrupts the time and style, and people no longer feel like dancing.

Elements of Improvisation

With young bands, I teach the rhythm section how to vamp over a dominant chord. This includes teaching the bass player how to play a simple walking bass line and teaching the piano player a five-note voicing with which he can experiment. I pick up my horn, play figures to the band, and have them play these back to me in a call and response. Many directors worry about what notes students should play and not what rhythms they are being taught to use, but to make an improvised solo work on a dance tune, which is almost anything in swing or Latin style, the solo has to fit rhythmically even if the lines are simple. Finding a few simple notes, such as the thirds, sevenths, and ninths, and then creating easy rhythms that students can play after hearing them are good exercises. This is akin to a simple transcription exercise. I use call and response frequently to give young soloists some initial encouragement and ideas to start improvising.

Stop Conducting

There is substantial debate about how much, if any, conducting is necessary during a jazz ensemble rehearsal or performance. The more advanced the band the less the director should do. Many of the top groups, such as the Airmen of Note, operate without a conductor. The drummer kicks off the chart and the lead alto gives a cutoff. They have someone who rehearses the band, but at concerts there is no director. In the Basie band, Basie was the piano player, and he would just stand up and direct when needed. What he was doing was more showmanship than directing.

Just as a concert band conductor might start a march in rehearsal and then walk around the room to correct problems as the group is playing, much of the jazz ensemble director’s time can be spent away from the front of the band. This forces students to focus on music, count independently, make correct entrances and releases, and listen to each other and especially to the rhythm section players.

As a director moves around the ensemble it is important to listen without looking at the score. Walk through and behind the rhythm section, and look over the piano player’s shoulders to check the voicings and rhythms he is using for comping. I might also walk way away from the ensemble just to remind them that they don’t need me. I should not have to remind them to come back in after a solo section or where a sax soli is.

One useful thing a director can do during rehearsals is move attention off of the soloist. A lot of times a director will focus on the soloist, which can cause unnecessary anxiety for a student still working on chord changes and developing ideas. During a sax solo I might talk to the trumpet players about the next entrance or something they just played. This is an opportunity to make adjustments without stopping the band.

If students have been well prepared, the jazz director need only make students feel comfortable at performances. Being in front of the band during full ensemble sections of playing is primarily to remind them of the large stylistic elements of the music, rarely the time.

Change Something

I have changed the lighting in my rehearsal room to alter the mood. With a college band I worked with over the last few years, I brought the jazz fronts and stand lights to dress rehearsal and turned off all the lights in the band room so students became accustomed to reading with the lights for the performance. This heightened the level of the dress rehearsal because everybody got psyched about something new.

Using a variety of rehearsal configurations is a simple strategy to keep things interesting for both students and director. I am always amazed to see the energy and excitement expressed on the faces of students when they enter the rehearsal room on a day I changed the seating configuration. I sometimes put a small seating diagram on the chalkboard to stave off confusion. This technique seems similar to changing your living room furniture around. Suddenly, you are once again excited about being there. In addition, changing rehearsal seating configurations is also a great technique to make students more aware of what other instruments are doing as they play. Here are some suggestions for changing the rehearsal set-up, the first two of which can also be used at concerts, where they will have much the same exciting effect on the audience as they did with the students.

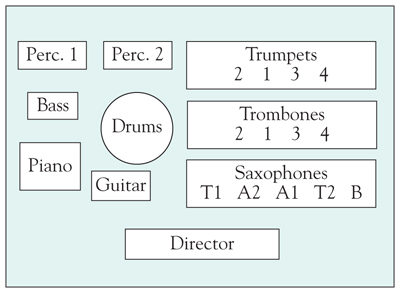

Standard Block

The rhythm section should be set up to the left of the winds, with the bass player and ride cymbal of the drum set as close as possible to each other. For good nonverbal communication rhythm section players should be close to each other and easily able to make eye contact. The winds should be in three horizontal lines to the right of the rhythm section, with the trombone section lining up horizontally with the hi-hat cymbal of the drum set. The trumpets should be 3-5 feet behind the trombones, and the saxes should be 3-5 feet in front. Lead players in each section should be in the middle of their row and aligned vertically amongst the wind section. Vary this for rehearsal by having the saxes arched in front, the saxes facing the brass section, or even the trumpets sitting in front with the saxes standing in back.

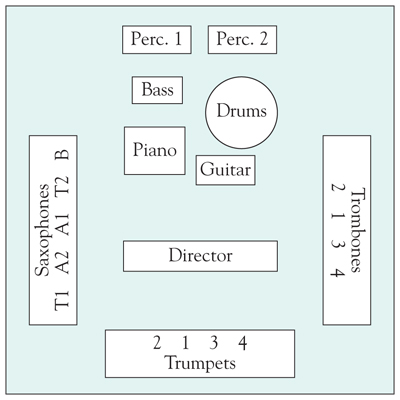

V Formation

The rhythm section should be placed in the middle of the stage but configured as they are in the Standard Block. The trombone, trumpet, and sax section rows are placed to the left, behind, and to the right of the rhythm section respectively, with the trumpets on risers so they can be seen over the rhythm section. This configuration is reminiscent of old show bands like the Stan Kenton Orchestra.

.jpg)

Box Formation

Each of the four sections of the band creates one side of a large square facing inward, with each row maintaining the same configuration as in the Standard Block. Use this set-up in rehearsals, but not performances.

Spread Out

The rhythm section is placed in the center of the room, similar to the V set-up. Wind players should spread out randomly as much as possible, facing towards the rhythm section.

Look Professional

While getting the band to play well should be the first item on a director’s list of priorities, getting them to look good should not be far behind. Consider the way a concert band looks on stage when all the students are in similar black and white attire with rows of chairs and stands evenly spaced, or recall the polished look of a marching band as it enters and exits the field with nearly perfect intervallic distances between the members.

A jazz band should look equally sharp. All black is the easiest, least expensive, and quickest way to produce a clean, professional look. It is worth taking a few extra moments to straighten chairs, spacing them evenly on stage and keeping the set-up as symmetrical and balanced as possible from the audience’s perspective.

Students should consider themselves to be performing from the moment they enter the stage to the moment they exit. In many cases, the stage is more than the place where the music will be performed; it is the entire campus of any place the ensemble visits. Students should act professionally even in the hallways of buildings. Part of teaching students to act professionally includes discussing what types of warmups are appropriate. First impressions are everything, and taking a few extra steps to get students to look and act professionally will impress the audience.

Buy the jazz ensemble some fronts, traditional short music stands that contain the logo of the band or other artwork. Using fronts gives the band a traditional stage band look, keeps horn angles more uniform, and hides mutes, cables, and other eyesores. It will also make the band members feel distinct from other ensembles in the school and more professional. Directors with small budgets might ask a local business to buy them for the band in exchange for displaying a stick-on logo on the fronts for one or two concerts.

The low level of most fronts can lead students to play with poor upper body position if the director does not carefully address posture. Saxophonists who play with fronts can still play with good posture. I have students sit up straight, and when posture is set I have them bend at the waist without curving the spine.

Showmanship

Showmanship

I like to build stage entrances into a show. One idea I use is to have the rhythm section enter first and begin a vamp that can lead into a Basie chart. Horn players come out one by one, and I am the last one to walk on stage, at which point I immediately start the chart. The crowd loves this, and it prevents students from going out on the stage and showing off. I avoid tuning on stage because it shows the audience how out of tune an ensemble is before the performance even starts.

Soloists should stand up, and have all the saxes stand up during a soli. It is purposely flashy and reminds the audience to focus on that section. If the ensemble plays a Glenn Miller chart I will add choreography by having trombones extend their slides in a dramatic way at certain parts of a chart or having trumpet players turn to the left 20 degrees for a hit, just to add a visual effect. Ellington would sometimes conduct with a giant 22-inch baton, and it was just part of the act. Audiences love it, and it magically makes them think the band sounds better, too.

The younger the ensemble, the more the director is there as encouragement for the band. I try to direct the audience’s attention where they should be listening. During a saxophone section soli, I make sure I am not standing in front of them. I might stand next to the bari sax and just watch the sax section and bob my head a bit. It is important for a director to appear calm, cool, and collected. A tense director brings unnecessary attention to weaknesses in the band that the audience might not have otherwise noticed.

Put Students to Work

I love bands that start by having the drummer kick off a chart. I also like bands that give each member of the band a responsibility, such as booking tours, setting up sound equipment, organizing music, and handling advertising. Even with a high school group I will set up leadership within the band. Every time we rehearse, a student is responsible for coming in before class to make sure that the spacing between chairs is good and the trombones are lined up with the hi-hat in the rhythm section. The bass amp should be behind the drumset but with enough room between the piano player and the drumset for the bass player to fit an acoustic bass. The piano should be turned so the pianist can see the drummer and bass player without having to strain. With a good band all of these things are present, even if the audience never notices such details.

Jazz band rehearsals and performances ought to be as carefully conceived and structured as those for any other ensemble. The power of jazz ensembles of all ability levels to get people excited about music should never be underestimated, but realizing that potential depends on the planning and energy given to each rehearsal and performance.