When students begin playing extended techniques early, they are not intimidated by them in advanced material.

The benefits of studying extended techniques include a greater ability to project and increased expressive capabilities, among many others. In my teaching I have focused on developing extended techniques with students at all levels. My aim is to eliminate bias against new music by introducing students to different sounds when they are young.

The benefits of studying extended techniques include a greater ability to project and increased expressive capabilities, among many others. In my teaching I have focused on developing extended techniques with students at all levels. My aim is to eliminate bias against new music by introducing students to different sounds when they are young.

When asked, many flutists say that they are not ready to play new music with extended techniques. This surprises me because everybody is ready. Many extended techniques are no harder than traditional flute playing. Some are even easier. I recently gave a masterclass to university flute majors who had not yet learned extended techniques. As an introduction, they played Viktor Fortin’s No Problem, 14 Easy Duets. Although they are aimed at intermediate-level players, there were lessons to be learned for everyone.

The duets are tonal with conventional rhythms, which made them easily sightread at the university level, and the melodies are catchy, jazzy, and fun. Each duet is structured so that both parts alternate playing a specific extended technique. The music is composed tonally and melodically with the key clicks and flutter tongue adding humor. The reaction from both flutists at the end of the first reading was laughter and high-fives, a startling contrast to the usual reaction from conventional flute playing.

While working on the duets, the students faced the challenges of finding the appropriate speed of flutter tongue; coordination with key clicks; weak diaphragm movements in tongue rams; and intonation within harmonics.

Flutter Tongue Speed

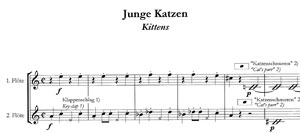

Two flutists played "Kittens", a duet in the collection that emphasizes key clicks and flutter tongueing. Although they were able to produce the flutter easily, they were unsure how fast it should be. The score describes it as the cat’s purr. To produce it you cover the entire embouchure hole and flutter into the closed embouchure hole.

We discussed the speed and pressure of the flutter, as one flutists’ production made the kitten sound a bit too angry, or not kitten-like at all. For a lighter sound, flutter with the tip of the tongue further back in the mouth away from the teeth and decrease the amount of air blown.

Another option is to use a uvular or throat flutter for a lighter sound. Keeping the uvular flutter low in the throat slows it down. When a uvular flutter gets too high in the throat, the speed is too fast and the sound distorts. In this particular instance, use less air than in normal flute playing, as the aim is not to produce any tone. Robert Dick has remarked that the problem with most flutists’ flutter tongue is that it is not used creatively. This duet gives even advanced players a fun opportunity to experiment with it.

Key Click Coordination

There is a temptation to take the flute away from the mouth while playing key clicks, but it has to stay in playing position for the correct pitch to sound. When moved away from the mouth, key clicks sound a minor second higher. When the embouchure hole is covered, the key clicks sound a major seventh lower. One flutist playing key clicks for the first time found it difficult to coordinate them without blowing into the flute as she is used to doing. In order to compensate, she put the flute down.

Tongue Rams

“The Tongue-Breaker” is the eighth duet in the collection. It is a fun one-page piece that emphasizes tongue-rams and is meant to be swung. It is also good for teaching the amount of diaphragm movement needed to make the tongue ram sound at an appropriate volume. Tongue rams sound extremely soft in comparison to a normal flute tone. For them to sound intentional and not like a mistake, an exaggerated diaphragm contraction or kick is necessary. The kick puts enough air into the embouchure hole before the air is cut off by the tongue.

The flutists found isolated tongue rams, not part of a musical line, easy to execute by keeping the flute in playing position and simply rolling it in. More of a challenge were tongue rams that were within the duet. From this duet students learn that new techniques are more physical and require a higher energy level than they are used to providing. That experience alone is beneficial and applicable to traditional repertoire.

Harmonics and Intonation

The other duets played during the class were “Parrots’ Tete-a-tete” and “Hard and Soft,” both of which use bisbigliando, a timbral trill between traditional and harmonic fingerings. The discussion of intonation that surfaced when I introduced the technique was noteworthy. One flutist wanted to turn the flute inwards to produce the harmonics, but that limited the resonance and made the tones very flat. Just push the lips and jaw forward to keep a constant color. Students who work on these duets will gain more control over their intonation and develop embouchure flexibility as well.

These fun duets are a non-threatening introduction to extended techniques. High school flutists, or even middle school students, would have fun learning one technique at a time before they move on to more difficult new repertoire.

The following are additional repertoire recommendations for each grade level. This list was created to eliminate radical jumps in difficulty or musical style. In fact, I’ve found a surprising amount of resources, especially for intermediate to early advanced students.

Level One Repertoire

Phyllis Avidan Louke has written two volumes of extended technique pieces that are suitable for beginners, even in their first year of study. The first is Extended Techniques-Double the Fun (2003) written in a playful style with short duets lasting about one minute each. Her second book is Extended Techniques-Solos for Fun (2006), in which the piano accompaniment can substitute for the second flute part.

A beginning flutist could play the second flute part and gain exposure to extended techniques while another student or teacher plays the upper line. The pieces are descriptive and encourage creativity.

One piece called “Fright Night” asks for experimentation making spooky noises on the flute. It also uses wind noises and pitch bends, which a beginner can have fun with. The idea of teaching pitch bending to a beginner is also beneficial as it introduces intonation early on. In the duet book, she writes “Chopsticks” and “Horse Trot” for two flutes using only key clicks. These books not only introduce extended techniques well; they also foster the imaginations of developing flutists.

Level Two Repertoire

Louke’s books could also be used with slightly more advanced students. Linda Holland’s Easing into Extended Techniques (2000) and Fortin’s No Problem (2006) mentioned earlier are also good. Holland has five volumes that focus on microtones, harmonics, multiphonics, bends and slides, and singing while playing. She writes, “The non-virtuosic nature of the music allows flutists of an intermediate level and above to ease into these important 20th-century sounds.”

Fortin’s book also has one duet focusing on each technique. In a range for an intermediate flutist, it can be played with either a teacher or a fellow student, as both duet parts are equally written. Players take turns with the techniques and are given a break between them with traditional writing.

Advanced students could also use these books as an introduction to extended techniques; there is room for growth in them. A beginning student might find the new noises fun, but a more advanced student could work on refining the effects for a more cohesive musical statement. Above all, the works discussed here are enjoyable and creative.

Level Three Repertoire

By the time a student reaches high school, there are many pieces that can be studied. Robert Dick’s works fit nicely into this category. He has written some jazz- and rock-based pieces that bridge into the world of modern music without overwhelming students. He details the playing instructions meticulously, and the scores are easy to follow. All of the alternate fingerings are notated right in the part. The print is large and the rhythms are simple. However, these pieces challenge students as they must re-orient themselves with new fingerings and playing styles. His pieces require some improvisation and a high degree of interpretation.

Lookout is a rock piece that was written for the N.F.A. 1989 High School Soloist Competition. Flying Lessons Volume I (1987) and Flying Lessons Volume II (1987) fit in level three as well. Other choices, depending on the preferences of the player, are Techno Yaman (2001), a piece based on a traditional Indian Raga played with a drum machine, and Or (1981), an introspective piece using small interval multiphonics.

Students who enjoyed Debussy’s Syrinx (1913) could continue with works of Giacinto Scelsi or Kuzuo Fukushima. They require minimal extended techniques and introduce a style that is more in line with classical playing. Scelsi wrote a solo flute piece, Pwyll (1954) and a solo alto flute piece, Quays (1953) which can also be played on the C flute. Fukushima’s Mei (1962) uses extended techniques sparsely and slowly.

Level Four Repertoire

If advanced high school have limited knowledge of these techniques and repertoire, start with some basics such as at least one work by Robert Dick, Edgard Varese’s Density 21.5 (1936), and Messiaen’s Le Merle Noir (1952). An advanced college student who has played these pieces should be able to continue with more difficult repertoire.

Aurele Nicolet has compiled a selection of short pieces, Pro Musica Nova: Studium zum Spielen Neuer Musik für Flöte that are increasingly difficult but nonetheless concise. The collection introduces students to works that are a good pre-cursor to studying longer works. Klaus Huber’s Ein Hauch von Unzeit (1972) and Heinz Holliger’s Lied (1971) are both pieces to consider as well. Also in this category, a seminal work not to be missed, is Toru Takemitsu’s Voice (1971). Shirish Korde’s Tenderness of Cranes (1991) is a longer solo piece using pictorial images of Japanese cranes in flight.

Level Five Repertoire

These pieces include polyrhythms, virtuosic microtonal passages, quick interplay of techniques, circular breathing, and dense notation. Pieces at this level often appear on competition lists, and flutists lacking experience in level four repertoire would have a difficult time learning them.

Written for the 2004 Internationaler Musikwettbewerb der ARD München, Georg Friedrich Haas’s Finale (2004) is virtuosically microtonal. The majority of the piece is fast with large leaps between quarter-tone intervals. The range of microtonality incorporates all three octaves of the flute. Bernhard Lang’s Schrift I (2003) alternates between many techniques quickly and within difficult rhythms. Breathing is also prescribed in certain sections. Lang uses a loop or techno feel in his compositions that, for the listener, masks the intensity of the writing. The 2005 Jean-Pierre Rampal Flute Competition required a few pieces that fit into this repertoire level. Heinz Holliger’s (t)air(e) (1980-83) is often performed in new music circles. Salvatore Sciarrino’s, L’opera per flauto (1977) is a long but rewarding work for the most ambitious flutists.

The works of Brian Ferneyhough are at the end of the complexity spectrum and for flutists already immersed in new music. They are philosophical and the scores are extremely dense. He layers techniques on top of one another and admits that there are sections that are unplayable. Those looking for more advanced pieces will find a comprehensive graded repertoire guide on Helen Bledsoe’s website. www.helenbledsoe.com

Extended techniques strengthen traditional flute playing and foster imagination. Simply putting order to the repertoire enables more flutists to dive into new music. I am all for opening up the world of new flute sounds for as many young flutists as possible.