It is one thing to learn from an orchestra, but quite another to love one. I have done both. Growing up in Milwaukee in the late 1950s, I began trombone lessons and quickly fell in love with classical music. Back then, band repertoire consisted mostly of numerous orchestral transcriptions. As a result, I wanted to hear professional performances of the pieces my bands were playing. Fortunately, there were two series of concerts on radio and television, that allowed me to listen to some of them and ultimately influenced me greatly – the televised Leonard Bernstein: Young People’s Concerts, and a weekly NBC radio documentary series entitled Toscanini: The Man Behind the Legend. Taping them with my trusty reel-to-reel tape recorder, I listened countless times to many of the great classics.

In addition, shopping at a store called Radio Doctors, I purchased as many records as I could afford, including an LP vinyl recording of a piece I had never heard before, The Pines of Rome composed by Ottorino Respighi and recorded by Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony. That did it. I was thunderstruck. To my ears the sound of that music was sensational and almost beyond belief. A love affair began. By the time I reached high school, I was first chair in the concert band and principal trombone in the orchestra. During my junior year my orchestra director offered me a ticket to an orchestra concert to be played at the Pabst Theatre that night. I couldn’t believe it. I was going to attend a live performance by the CSO.

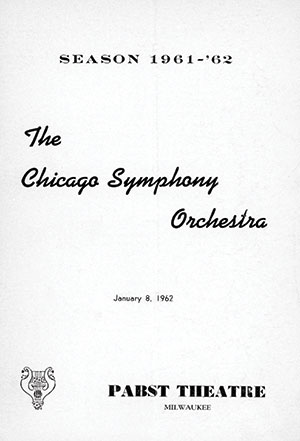

On that cold, snowy January evening I rode a city bus to the area, then trudged a short distance to the theatre. I was early and as I approached the building, a sleek, black limo pulled up to the curb. The car door swung open and out stepped a tall, slender, older gentleman wearing a long black overcoat. As he walked carefully to the building’s side entrance, I wondered who it was, but kept moving so that I could get inside, warm up, and find my seat. After presenting my ticket I began a journey to the upper balcony and to a straight-backed iron seat with practically no leg room, set at such a steep angle I thought I might topple forward and plunge to the main floor and certain death.

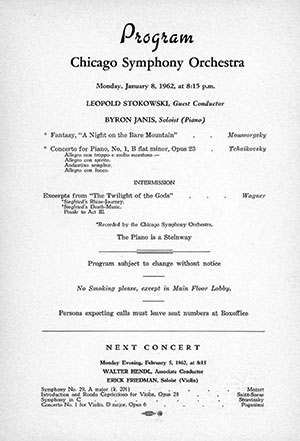

I opened the program and read that Leopold Stokowski (the man in the long black coat) would conduct that night rather than Fritz Reiner. Many of the musicians were on stage warming up and tuning, so I studied the printed program notes. Those descriptions seemed perfectly written and proved invaluable for understanding the music to come.

Eventually, from my great view up in the crow’s nest, I noticed that the musicians did not look properly dressed. They wore business suits and sport coats rather than formal attire. The concert was scheduled for 8, but as 25 minutes ticked by, I wondered about the delay. Just then, the lights in the auditorium dimmed and Leopold Stokowski – resplendent in white tie and tails – walked out as if he had stepped directly out of Fantasia.

He bowed majestically to the audience, then turned to the orchestra launching into the Mussorgsky A Night on the Bare Mountain with all the witch’s scratches, screeches, shrieks, and groans ending with the ring of a church bell and dawn. I will never forget the look and shadows cast by Stokowski’s hands, his movements and gestures – no baton, elegant, a sculptor shaping sounds. It was exhilarating and mystical. The Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1, played brilliantly by the young Byron Janis, soared through the hall in perfect balance with the orchestra under the older maestro’s control. Following intermission, the concert concluded with excerpts from Wagner’s Twilight of the Gods. The music was full of dramatic fire and brimstone astoundingly played by the brass section such as I had never heard in my life. I don’t remember much after the concert except an afterglow and the anticipation of newspaper reviews the next day. This performance meant more to me than I realized in the moment.

The next morning, I raced out to the front porch to pick up the Milwaukee Sentinel with the concert headline “Stokowski, Janis Shine in Concert.” The glowing review included details about the late start to the concert. Because the baggage car was delayed by the winter weather, the musicians had no time to don their formal duds, as was reported in the Milwaukee Journal review that evening. Stokowski was called a master Wagnerian interpreter and the Chicago Symphony was described as splendid, dramatic, and exciting. I knew I would have to hear the CSO as often and for as far into the future as possible.

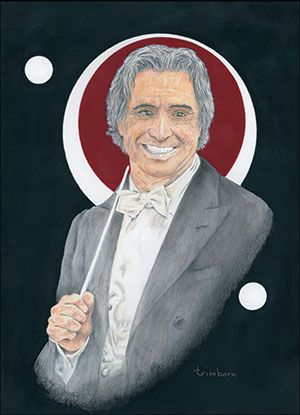

Recognized as a “Maestro Among Maestros” – CSO Music Director Ricardo Muti

celebrated 50 years as a conductor in 2018. Portrait by the author.

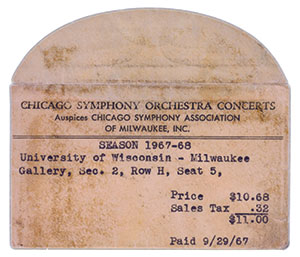

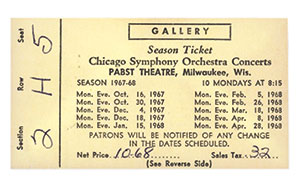

In college, I heard the Chicago Symphony regularly at the Pabst. Each concert taught me something. Later, teaching in the Chicago suburbs, I took my high school bands to Friday afternoon performances at Orchestra Hall. The bus rides home were remarkable as students marveled at what they had heard and then talked about the programs for weeks. Over almost 50 years, the CSO has been a personal, professional, and essential part of my life.

Beginning with that first Stokowski concert, I have learned many things from the conductors at the helm and the legendary musicians under their leadership. The sublime orchestral sound as molded by Fritz Reiner, to my ears, endures. Since his time, each successive director has brought a fresh aspect to that sound including Martinon’s focus on French and contemporary works, the contrasting styles between Giulini’s lyricism and Solti’s drama, and Barenboim’s fresh, bracing interpretations. Haitink showed seasoned elegance and power without bombast while perhaps the greatest living conductor, Ricardo Muti, consistently summons orchestral playing in a wonderfully singing, cantabile manner that evokes feelings in listeners beyond words.

Recognized as a "Maestro Among Maestros" – CSO Music Director Ricardo Muti celebrated 50 years as a conductor in 2018. Portrait by the author.

Lessons Learned from the CSO

Listen extensively and critically to great live and recorded music performed by wonderful artists. Have students do the same. Ask for feedback concerning personal performance. There is always plenty to learn after a concert or recital. Experience music as originally written, not just through arrangements or alternations. One can develop the finest concepts of specific sounds (ensemble, solo, combinations).

Seek out performance reviews and critically evaluate them. Habitually compare and evaluate what conductors, individual musicians, and ensembles bring to performances of the same works. A rendition can vary from routine to magnificent. The notes and spaces between them on a page must come to life, and when the greatest musicians make that happen, it creates momentous and lasting interpretations.

Study program notes to appreciate the perspective, history, and understanding they can provide. Little did I realize that the program notes I so admired were written by Arrand Parsons, in whose class I sat many years later at Northwestern University and whose insights remain with me. Those program notes were important to me on that magical night long ago, and consequently later on, because I always provided notes for my concert audiences, educating them and my students, perhaps more than I ever could from the podium.

Do not let off-stage problems prevent focus on the performance at hand. Close to 60 years ago on a wintry night, I didn’t understand why a concert started late, but it went on without a hint of drama behind the scenes.

Experience performances not only focused on technical details but more importantly on an aesthetic level. Cherish the music in all of its mystery and power.

Although I have spent most of my career conducting bands and choirs, the sense of ensemble, balance, attack, and clarity has been embedded in my mind’s ear by listening to an iconic organization. Best of all, I continue to learn from and love the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.