The first feature an audience hears is a flutist’s sound. Unfortunately the sound the audience hears is quite different from what the flutist hears. When flutists learn what they actually project to an audience, they can figure out what to do to present their ideal sound.

In 1962 I traveled to Raymond, Maine to study with William Morris Kincaid, the legendary principal flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra and father of the American school of flute playing. I joined a handful of flutists who lived on the second floor of a rambling New England farmhouse owned by Mr. and Mrs. John Cobb. While the Cobbs worked in Portland, they grew blueberries on their farmland. Since we were poor students, who had spent every penny we had on lessons with the master, the blueberries that we picked added a delightful addition to our staple of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. A neighbor often brought fresh fish (cleaned and filleted) and newly picked corn-on-the-cob. Mrs. Cobb had every flutist sign her guest book. When reading through the book, I truly realized the lineage of great flutists Kincaid had taught over the years. I was surprised to learn that my first teacher, Sterling Hanson, had been a Kincaid pupil years before.

The Cobb farm was on one side of Lake Sebago, and Kincaid lived on the opposite side. Several mornings a week a young neighbor of Kincaid’s arrived at our dock to take two or three of us across the lake for lessons. I usually took three lessons a week, but others took one or two. There was a boathouse on Kincaid’s property where he stored his boat in the winter. In the summers the boathouse doubled as a warmup room where we waited while one of the others had a lesson. The boathouse was stocked with programs of previous Philadelphia Orchestra seasons and books that I would later find were on most university lists of 100 novels to read if you wanted to be an educated person. Now I realize he started teaching me before I got my flute out of the case. I loved reading the program notes about the compositions that were performed and the soloists and conductors who appeared with the orchestra. From perusing his fiction collection, I became a lifelong reader of novels. About ten minutes before my lesson time, I walked up the hill and sat at the picnic table outside his front door until it was my turn. I remember so clearly the first time I sat there and listened to the magical sounds emitting from Kincaid’s log cabin. These flute sounds were the most beautiful I had ever heard, and I knew that I had come to the right teacher to find answers to my questions.

I was nervous to be in the presence of this towering figure. Kincaid was well over six feet tall with flowing white hair. He was a swimmer and in excellent physical condition. My lesson began with an attempt to isolate one whistle tone pitch while fingering a low C and then progressed to an exercise that was sometimes called Praeludium, Prelude, V7 Warmup, or Vocalise. (See Patricia George’s Extras for a copy.) Evidently I wasn’t doing the Praeludium correctly, so Kincaid, who always had flute in hand and stood facing you on your left, demonstrated what I should be doing with the phrasing. At that moment I did not hear what he was showing me about phrasing; I was so shocked by his sound. What had sounded so glorious outside at the picnic table was now very airy. My first thought was, “Oh my, he has lost his sound.” I was too embarrassed to say anything though the horror on my face probably told him of my concern. We finished the lesson, and I received my assignment for the next lesson that was two days later.

Over the next days I practiced six to eight hours a day. At my next lesson I was feeling more relaxed, so when he asked me if I had any questions, I said, “Yes, tell me about your tone.” He smiled knowingly and asked what I wanted to know. I told him that while I was waiting at the picnic table for my first lesson I had heard the most glorious sound coming from him, yet when he demonstrated at my lesson, the tone was a bit airy. I wanted to know what had happened. His answer was one of the best lessons in my life. He explained that he was playing with a “cushion of air” around the tone so it would project to the cheap seats in the top balcony where all the students sat. He continued to clarify that if the tone was too clean on stage there was nothing to propel the sound into the audience, but if the tone had the cushion of air, that cushion sent the sound to the back of the hall. He suggested I visualize a funnel. I was to produce a sound which looked like the big end of the funnel not the small end. I should produce this sound by setting my lips as if I were playing the third partial of a D4 and keep them in this position for the other notes on the flute. This led to my aiming the air quite high on the embouchure hole wall. If I could sometimes hear a whistle tone on a note, that was good too.

I continued my study with Kincaid throughout the next school year while I was a student at Eastman. I traveled there every few weekends for a double lesson on Saturday and Sunday. Joseph Mariano, my professor at Eastman and a Kincaid student himself, endorsed this study, and each time I returned from my weekend adventure, Mariano asked affectionately, “What is the old man thinking about?” I think Mariano loved hearing about my Kincaid lessons as much as I enjoyed taking them. The next summer Kincaid was ill so he arranged for me to study with Julius Baker in New York City.

My first lesson with Julius Baker was in the early evening. I rode the elevator down from the fifth floor apartment where I was house-sitting to Baker’s second floor apartment. This apartment on West End was quite large and sparsely furnished as he had just moved in. Baker asked me what I had brought for the lesson and I played the Mozart Concerto in G, K. 313 and the Ibert Flute Concerto. After I had finished playing the entire two works, he asked, “Why did you come to me?” I said, “Because I think you can help me become a better flute player.” He said, “You are already a good flute player, let’s play duets.” And, we did.

A few days later after many long hours of practice on my part, we began formal lessons in a room that Baker was converting to a flute studio for practice, teaching, and recording. I was struck that in an apartment that had so few furnishings, the flute studio had several large free-standing portable walls that were covered in speaker cloth (a sort of basket weave fabric). I asked him what they were for, and he explained that he used them as a filter when he was recording. He stood on one side and placed the microphone on the other side of several of the freestanding walls. He explained that the fabric filtered out the airiness in his tone. He was using the “cushion of air” technique that Kincaid had spoken of and obviously had taught Baker to do.

I use this technique most of the time when I am playing. However, when I am making a recording where a microphone is placed very close to me, I clean the tone a bit more. Remember though a cleaned tone will not project as well as tone surrounded with the cushion of air. Along with playing with a cushion of air, the player must choose what color of sound he wishes to use. The spectrum could be from very light to one that is quite dark. Flutists also speak of whether the tone is bright, full, or resonant. To work on one of these objectives you may voice your sound by playing either the 2nd, 3rd or 4th partial and then holding the embouchure in this position as you play the written passage. In other words I can overblow a low D up one octave to the second partial and then keep my lips in that forward position while I play a passage. Or, I could overblow up to the third partial and keep my lips in that ever more forward position while I play the same passage. Whether you choose to voice your sound from the 2nd, 3rd, or 4th partial is your choice. The goal though is to be able to keep the chosen sound throughout the flute’s range.

In a masterclass this past summer, Utah Symphony principal oboist Robert Stephenson was asked what an audition committee is listening for when the performer is playing behind the screen. Besides the obvious, he said the committee was listening for a player with a homogenous sound throughout the range.

Marcel Moyse shared his concern of making the tones of the flute homogenous. The first exercise in the De La Sonorite explores half-steps as it works its way down and then up the flute range. The player should try to keep the sound homogenous throughout. Flutists can achieve this by partly being still, keeping the embouchure stable, and blowing air very evenly. Of course players should listen intently to be sure they achieve the objective.

The major question for a player is, “What do I sound like in the audience?” One answer is to place a microphone a few hundred feet out into the seats and make a recording.

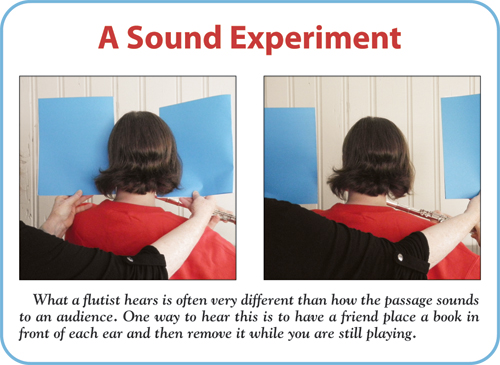

Another good experiment is one that I learned in drama class. Place your hands in front of your ears with the palms facing toward the back. Listen to your speaking voice while reciting the alphabet. Continue reciting the alphabet while removing your hands. Notice the difference between your perception of your speaking voice with and without your hands in this position. Duplicate the exercise while playing the flute by having a friend place a book in front of each ear and then removing it while you are still playing as shown below. I often use this exercise with students to show them how different a passage sounds to an audience.

In another drama class a professor assigned me to read into the corner of a room for fifteen minutes a day to improve my speaking voice. This idea worked very well too. When I was at Eastman, I noticed Mariano warming up by playing fortissimo octaves while standing very close to one of his studio windows, a modification of my drama teacher’s exercise.

My sound advice to flutists is to strive for an even homogenous sound throughout the range. Remember that a cushion of air around a well-formulated sound projects best to the back of the hall, and a sound that includes more of the higher partials is more interesting to listen to and blends well with other instruments.