The fundamental acoustical characteristics of the flute can create an ongoing struggle for flutists. The low octave is naturally softer than the high octave, and most flutists have spent hours trying to honk out the low notes and whisper in the high register. Legato, phrasing, expression, and technique all benefit from an understanding of this issue.

Vocal or Not

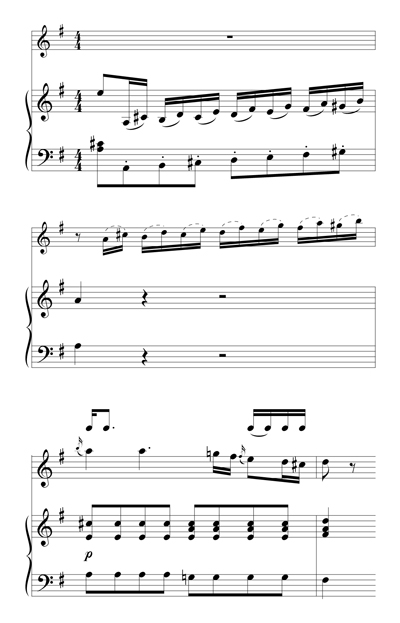

Flutists traditionally have played using a vocal approach. A round vowel is built into the instrument, higher notes are louder and lower softer. Much has changed over the years, but still most of the music is undoubtedly intended to sound vocal to some degree. Additionally most music, old and new, generally follows these characteristics in terms of energy: climaxes usually happen at high points, and lower pitches often contain the least musical drama. In terms of phrase shaping, as a general rule, there should be more emphasis at the higher part of the phrase. For example, in the opening of J.S. Bach’s Sonata in E Major, emphasis at the top of the musical line occurs naturally.

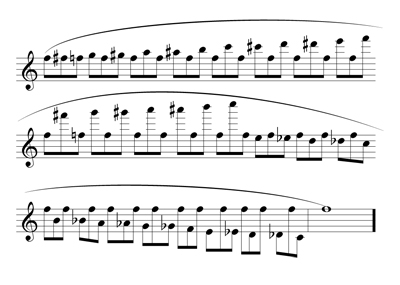

As certain types of music gradually became liberated from the church and contained more references to personal human drama, so too did instrumental practice become free of the constraints of vocal imitation. Instrument engineering followed suit. Theobald Boehm’s (1794-1881) modifications furthered the flute’s ability to expand the dynamic range. Flutists such as Charles Nicholson (1795-1837) became known for their tonal capabilities in the louder dynamics. Repertoire and studies for the flute became more technically and tonally challenging. Danish flutist and composer Joachim Andersen (1847-1909) wrote etudes for daily use in which a descending crescendo involving wide leaps is standard practice, as in his Etudes, Op.33, No. 24.

.jpg)

Voicing

In Andre Maquarre’s popular Daily Exercises for the Flute (1923) the first general rule in the book insists that one must imitate the natural dynamic tendencies of the human voice. Somewhat to the contrary, the concept behind Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite is uniformity of tone throughout the instrument, which implies the idea that the lower register of the instrument should be stronger. Change between the low and high registers should be seamless. The book includes specific studies for strengthening the tone of the low notes, encouraging equality between the low and high notes.

Trevor Wye Practice Book for Flute Volume 1, Tone, expands this notion further: the tone in the high notes is generated from the low register. He states: “Assuming that you wish to start by putting the roots of your future tone work firmly in the ground, practice the low register.” And, “let it be understood that unless the low register tone contains overtones or some richness and colour, the middle and high registers will be the more difficult.” This forms the basis for his entire series, extending to phrasing and intonation.

Thus, the idea is that the higher notes should be based on the strength of the fundamental first octave. By building the tone from the bottom up, one evens out the dynamics and tone of the instrument. This has real implications on interpretation and execution. For a good legato, notes should be balanced, or matched, as well as connected. The higher notes will not awkwardly stick out if the low notes are strong enough. Use of this concept can be called voicing, similar to the way a pianist will decide which chord tones to play louder.

In Mozart’s Concerto in G Major, voicing can be used to enhance the characterization of the phrase in this ascending passage.

Start the upward scale in thirds at forte as if to answer the orchestra’s gruff preceding statement, then reduce the dynamic at the top of the scale to complement the buoyant, light character of the next bar.

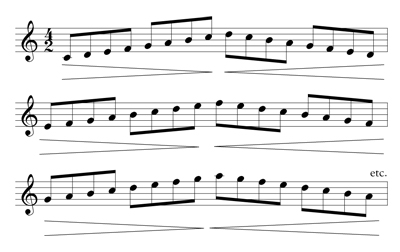

Composers of all periods do often require that rising figuration be played with a crescendo, as in Ibert’s Concerto, third movement. Here the crescendo and diminuendo are an integral part of the music, and should even be exaggerated. However, the primary melody of this section beginning at 52 is another story.

.jpg)

Think about balancing registers between the higher, longer note of the melody and the interspersed moving notes. Lean in to the triplets, even though they are much lower. They carry the momentum forward to the next long note. The last note of the triplet can be strong, and the higher long note emerges gently as a result. Remember that longer notes naturally sound louder than shorter notes.

.jpg)

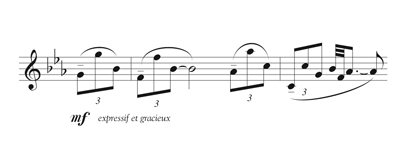

The opening theme of Reinecke’s “Undine” Sonata represents another example in which higher and lower notes must be balanced.

Voicing can affect the mysterious, dreamy atmosphere of the music. Fill out the lower notes, and de-emphasize the higher notes to achieve a poetic legato. Also, keep full dynamic and rhythmic value to the eighth notes or you will sound like you are bumbling about from quarter note to quarter note.

Flowing water is then depicted in fast scales for the piano. As the exposition closes, the flute takes up the idea, like water swiftly flowing into the distance.

.jpg)

Note that Reinecke purposely omits crescendo and diminuendo. The lower notes in the scale should be a bit louder, (especially right before the final ascending scale), and the top notes softer, making the scales sound placid.

Exercise No. 4 from Daily Exercises for Flute by Taffanel-Gaubert is a perfect vehicle for making this ascending scalar diminuendo a normal part of your playing vocabulary. Mr. Maquarre might be turning in his grave, but persist.

Immediately in the development section of the first movement, Reinecke presents a tough problem. Melodies which integrate intervals ascending to difficult notes like high E and F# contain particular challenges because these notes are often shrill and stand out.

.jpg)

Feed the B natural preceding the top F# plenty of air. When this note is louder, then the F# presents itself without screeching like a barn owl. It also helps to finger the F# with right-hand 2 instead of the standard fingering with right-hand 3.

Then Reinecke uses the natural tendencies of the instrument to create the effect of water cascading downward by starting the phrase in the high notes. Still, try to combat the tendency of the high G# to stick out awkwardly by voicing it.

.jpg)

In the opening phrases of Lowell Liebermann’s Sonata for Flute and Piano, first movement, mm. 13-17, there should be a very pronounced dynamic difference between the high and low registers in order for the top notes to fit in the line. Like the scale passage in the Reinecke example above, this melody is another example of the non-crescendo.

Here, the composer omits the crescendo from a passage where one would be expected or assumed. When you notice this, actually make a diminuendo up to the top notes. Do not sacrifice legato.

All intervals, even small ones, can benefit from voicing and should be considered in context, but octaves always deserve attention. Most of the time, the top note of the octave should not be louder than the preceding note, especially in this passage from Enesco’s Cantabile et Presto where the addition of the octave is an ornament of the melody.

This is not always the case. In the following solo from Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration, connect the octave seamlessly, but do not back away dynamically from the top of the octave; both notes should lead to the downbeat.

Loosen Down

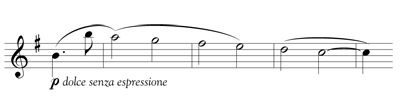

The basic skill of a descending crescendo should be firmly in place to achieve success with voicing. Interestingly, Trevor Wye actually indicates the crescendo in his version of Moyse’s famous chromatic study.

.jpg)

The ascending diminuendo is important as well, but if one cannot expand the low notes, the foundation of the tone is shaky. De La Sonorite also contains an advanced exercise which allows for work on equalizing volume in different octaves and working for tonal uniformity in intervals.

Attention to continuous blowing between the notes is important, especially when connecting notes into the low register, where the air column must travel slower. Relax the embouchure for flexibility.

With modern flutes, playing loudly in the low register has become commonplace, perhaps to a fault, and sometimes at the expense of tonal beauty throughout the instrument. With a greater range of choices about instrumental characteristics comes greater responsibility. Awareness of tonal characteristics, especially regarding voicing and balance, is more important than ever for the flute artist.