For teachers of elementary through advanced high school flutists, it is often a challenge to help students organize their practice time. Students are busier than ever before, and some parents sign students up for music lessons thinking the commitment will be limited to the one lesson per week. They are unprepared for the practice commitment. This fall, I spent time rethinking the practice sheet I give to my students each week. I had the advantage of parental perspective as my children are now 8 and 11 years old, and we are on the cusp of these busy years. I already see how difficult it is to fit in all the activities. My son participates in karate, school band, piano and horn lessons, and our church’s religious education program. It is not a huge amount of activities when compared to those of some of his classmates, but enough, I assure you. My son’s private teachers, understandably, expect him to practice 5 or 6 times a week, and I have to confess that it does not always happen.

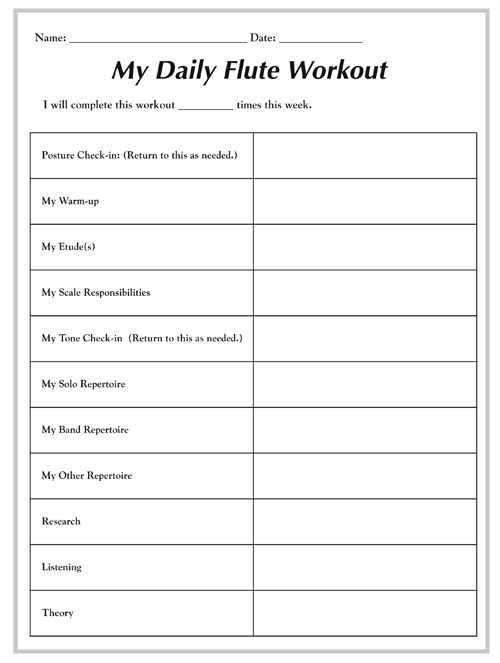

It was with this in mind that I developed the “My Daily Flute Workout,” a new and improved practice guide template, that my students and I prepare together at the end of each lesson. I wanted to make it absolutely clear to students and parents that I expect several practice sessions per week from them. I also wanted them to understand what these sessions entail and why they are important. Most of my students are involved in some type of sport or activity, so calling the practice sheet a workout resonates with them. It helps beginning students to understand that my expectations of their work input for flute lessons are the same as the those of their swimming coach. They would not dream of telling a swimming coach they can only practice once a week and they cannot expect to improve on flute with that work ethic either.

The word workout is also a useful reminder to the older students when they begin to complain of workload or practicing scales every week. Getting better on an instrument is work, but it can be fun work if both the student and the teacher participate in developing the guidelines and expectations each week. That’s why we call it playing the flute.

The template is a simple one, and I find that students are more willing to use it than my old sheet which was boringly titled Lesson Notes. The new sheet guides students to begin a practice session by thinking about posture. I encourage students to do this in front of a full length mirror to check stance, elbow placement, finger placement and movement. If there are bad habits we are trying to correct, I make practice suggestions next to the category Posture Alerts. The following pdf is the new workout sheet. pdf

The Warm-up

A warm-up should be just that, a time to warm up the flute, to warm up the body with deep breathing, and to warm up the fingers slowly. It is not a time to become microscopically critical about tone. (That comes later under Tone.) I have beginners warm up with headjoint exercises, many of which I have developed myself. Recently, I have begun using the Flute 101: Mastering the Basics series by Louke & George. The first book, Flute 101, includes two pages of headjoint exercises and smaller block insets throughout the book that are useful for warm-ups and may spark your imagination to create more. (Or ask the student to create their own.) For intermediate students, I add harmonics, octave leaps, and short finger exercise “bursts.” Students who are ready to incorporate vibrato use the exercises in Flute 102 or those in Christine Potter’s Vibrato Workbook. Vibrato is an excellent way to open up the tone, relax the throat, and tune in the ears.

The Etude

I know many teachers prefer to have students get their fingers moving before etudes by playing scales. I have found that students are more likely to practice if scales are not too close to the beginning of their session. Who wakes up in the morning and wants to play scales? (Ok, I do, but it takes years to create OCSD – Obsessive Compulsive Scale Disorder). My students tend to find etudes more fun than scales, so I put this block before scales on the sheet to lure them further into practice mode before I hit them with scales. Yes, I did use the words fun and etude in the same sentence. Be sure to take the student’s playing level, dedication, playing goals, and time availability for the week into consideration when choosing an etude or two. I find that students sometimes feel a greater sense of accomplishment when they complete two or three short etudes than one, long repetitive one. There are many wonderful etude books out there, and the Petrucci Music Library, www.imslp.org, also has free downloads of etudes in the public domain. Make sure the etude is a bit of a challenge, but not so difficult that students, especially younger students, become discouraged and give on up on practicing.

Scale Responsibilities

I word it that way for a reason. Often, teachers introduce a new scale each week or two at the lesson, and students are not completely clear on which scales they are responsible for practicing. The key to getting students to practice scales is variety. Emphasize straight scales, but also scales in thirds, arpeggios, and arpeggiated 7th chords, too. Encourage students to practice scales and arpeggios in a variety of articulations, dynamics, and rhythmic patterns. This is also a great time to use the mirror to check posture and finger position again.

Tone Check-in

At this point in the workout sheet the student is warmed up, and focused on practicing. This is a good time to focus on tone. My students use Trevor Wye’s classic Practice Book for Flute, Vol. 1 (Novello). I then promote them to Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite. This is where we get picky about tone. An unfocused or unprojected tone is considered a wrong note here. I tell students that on days when tone is good, they should go to the mirror and see what they are doing right with their lips. (Keep in mind that it might also be something they are doing with air.) Whether they play it beautifully or badly, they should notice what their lips are doing. They should write this information down or have someone photograph them with a phone. I tell students to not persist too long on a bad day. This only leads to tension and a worse sound. As Marcel Moyse said, “Put your flute in its bed, and go to bed yourself.”

Repertoire

I work together with students to determine appropriate repertoire. Considerations include upcoming performances, recordings, concerts, and competitions. Sometimes a student needs a technical or musical challenge or alternatively might be working through performance anxiety, in which case an easier piece might be better. For younger students, it is often a good idea to assign pieces in the key of the scales and etudes they are studying that week. For longer pieces, we develop a practice plan and outline where they should be by certain dates. Be sure students play repertoire from all periods and styles.

Students may not know how to practice repertoire. Teach them to identify and isolate problems. Practice with younger students in the lesson to teach them practice techniques they can use later. The goal is to create an independent, critically-thinking musician.

Band Repertoire

The local band directors really appreciate this block. I emphasize to students that whether they are first chair or tenth, they are part of a team (note the sports metaphor again) and should know their part perfectly. It is not necessary to practice all the music in the folder. I help them identify trouble spots if needed, and they can bring their band folder in if they need help on a section. I do request that they ask for this help at the beginning of the lesson.

Other Repertoire

This block is simply a useful organizing tool for students who are working on multiple pieces for various performances and competitions. We plan to have a piece ready to go several weeks before the actual event, and then it is moved to this block to marinate. If a student is in a small ensemble, this is a good point in the workout to practice challenging spots for that music.

Research, Theory, and Listening

Having taught courses in music literature and theory, I am passionate about the use of these tools for performing musicians. Students should understand the historical influences on a piece, the life of the composer, and the structure and style of the work. I rarely assign all three of these academic blocks in a lesson, unless the student is an aspiring music major.

A research assignment might include writing a paragraph or five bullet points about an era or composer, or about the circumstances surrounding the composition of a particular piece. A student struggling with performance anxiety may be asked to read and summarize a chapter in Eloise Ristad’s A Soprano on Her Head. Sometimes I ask students who have participated in summer study to write about their experience, so I can share it with the studio.

Music Theory Block

In the Music Theory block I may ask a younger student to drill fundamental techniques on a free music theory site, such as www.musictheory.net or www.emusictheory.com. (The rhythm drills on these sites are also helpful for older students who struggle with rhythm.) An older student studying a Baroque piece might do a Roman numeral analysis of a short section of a piece. It is amazing how quickly they pick this up. Sometimes students analyze the form of a piece or mark the main theme in a Rondo each time it returns. Students working on memorization may be challenged to create a memory map of the piece.

The Listening Block

It is easier than ever for students to listen to music at home. iTunes, Pandora, and YouTube make it simple for students to view and listen to performances. Be careful as the quality of video performances varies greatly. I ask my students to show me the video they listened to, and we often evaluate the performance together. This year, I have encouraged parents of my students to subscribe to Naxos Music Library (www.naxos.com). A one-year subscription is relatively inexpensive, and the quality of performances and recordings is good. (This is a different and much less expensive site than www.naxosmusiclibrary.com, which is used by many conservatories and universities.) Of course, I also encourage students to attend live concerts.

At the end of each lesson, the student and I decide together how many times to complete the daily workout before the next lesson. We take into consideration sports practices and games, tests, and special events. I tell students that five to six practice sessions per week is ideal and then ask how many sessions they feel comfortable completing. This way, the student and I both have a reasonable expectation for their preparedness level at the next lesson. We sometimes negotiate. If a student says that maybe three sessions are possible, I smile and suggest four. They always smile back and agree. Students keep the Daily Flute Workout sheets in a 3-ring binder, along with other handouts. I do not assign a specific amount of time to be spent on each item in the workout, or in each practice session, unless I feel a student needs extra help organizing practice sessions.

Since the implementation of the Daily Flute Workout in my studio, I have noticed an increase in the amount students practice, and in the intelligent way in which they approach this practice. They feel more responsible for their practice and progress, and as a teacher, it is much more fun to teach an engaged student.