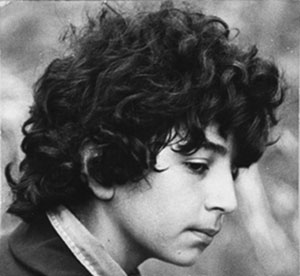

Upon hearing Jean Ferrandis for the first time, the legendary conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein commented, “It is Pan himself.” The story behind that first meeting is representative of the many doors that have opened quite by accident to Ferrandis throughout his career.

Upon hearing Jean Ferrandis for the first time, the legendary conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein commented, “It is Pan himself.” The story behind that first meeting is representative of the many doors that have opened quite by accident to Ferrandis throughout his career.

“It was the chance of a lifetime to meet Leonard Bernstein. He came to the Fontainebleau School near Paris as a tribute to the memory of Nadia Boulanger, who had been a faculty member there from the school’s beginning in 1921. I was in an orchestra for a conducting masterclass that Lenny was going to do, and it was my job to train the orchestra to accompany Mozart’s D-Major flute concerto. Lenny was not expected until the next day, but he arrived a day early – during our rehearsal.

“We were in the middle of the second movement of the Mozart, and I was playing from memory with my eyes closed. I heard a disturbance behind me, but thought it was just someone curious about what was going on in the room. We kept going, and when I finished the last movement and opened my eyes, there he was – sitting not five feet away with sun glasses and red flashy suspenders, holding a cigarette.

“I said, ‘Oh, you scared me,’ and he asked why. Then he said, ‘OK – we will practice the entire concerto.’ The plan had been to do only a small portion of the concerto during the masterclass, but we ended up doing the whole thing 12 times through. Later, he wrote a cadenza for the D Major for me and would introduce me to many great artists, the Orchestra of Vienna included.

“I said, ‘Oh, you scared me,’ and he asked why. Then he said, ‘OK – we will practice the entire concerto.’ The plan had been to do only a small portion of the concerto during the masterclass, but we ended up doing the whole thing 12 times through. Later, he wrote a cadenza for the D Major for me and would introduce me to many great artists, the Orchestra of Vienna included.

“I learned so much from him. He said to me in French, ‘a la vie a la mort.’ Lenny’s French was almost better than mine. He meant you have to practice your music and live life to the fullest in order to do your best. You have the right to play (as in have fun) when you perform. People forget how to have fun. You have the right to play, to make a mistake, and certainly to do and perform the opposite of what you practiced. There should be spontaneity and freedom when we perform.

“I will never forget his words. You should know the music so well that you can hear where it is going before you play it. If you play from the score, it’s already too late for musical freedom. When my life is rich and interesting, of course that goes into my music. I think Mozart said the same thing.”

Ferrandis is a kind, sensitive, sublime flutist who represents the future of the flute in France today. He travels extensively, playing and conducting, and when not on the road, he teaches in Paris at the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris. But that was not the life to which he was born.

Ferrandis grew up in Southern France in a non-musical family that has produced two fine musicians. “My parents were simple people, and we lived in a very small apartment. My mother wanted me to play music, but there was no space for a large instrument, such as the piano. We had to find an instrument that would fit the space.”

He started playing the flute at age 6 at the Nice Conservatoire and says that it came easily to him. “By the time I was about 12 years old I had finished all the basic repertoire. It was a difficult time for me, however, because I didn’t know if I really liked the flute that much. When I realized that I might prefer the violin I was 14, and it was too late to switch. So I had a little black period.

“Over time I began to understand that music is the most important thing, not the instrument, which is merely the means by which we play music. Now I am comfortable with the flute, and like it more and more because you can go very deep into the music with a flute.”

Ferrandis then launched into a philosophical discussion about the difference between pretty and beautiful, saying that it is easy to sound pretty on a flute, but much more difficult to sound beautiful. He was speaking about depth within the phrase as well as the sound. “Beauty is what is beneath the outward appearance. You can play the flute superficially quite easily, and lots of players do. However, my goal is to play beautifully. I don’t know if I reach that goal all the time, but that is what I want to do.”

His first teacher told him what was good or bad about his playing but never explained how to fix it. “I was still playing with the flute resting on my left shoulder at age 12, a habit that probably started because I was a very little kid when I started the flute, and it was too heavy for me. As I grew physically, nobody told me that playing with the headjoint on your left shoulder was unacceptable. Then when I was 13, I met Maxence Larrieu, who was surprised to hear music from someone who played with such poor posture. He got the flute off my shoulder.”

Ferrandis continued his studies at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Lyon with Larrieu and later also worked with Alain Marion in Paris. Then the competitions began. He won the 1982 Maria Canals Competition in Barcelona, the 1985 Young Concert Artists Competition in New York, and the Munich Competition, also in 1985. The following year he was awarded the Grand Prize in the Prague Spring Festival International Flute Competition.

Competitions

“The problem with competitions is not the music. The problem is that the juries sometimes come, not to listen to what the contestants are able to do but to hear what the contestants are not able to do. Contestants can feel that negative energy. However, it is very good for students to enter competitions, to move forward, to try to refocus and give their heart, even while being judged. Contestants eventually learn that the only way to perform is to love the music, the audience, and also the juries. Why not love the audience; they don’t judge you. They just listen, and like your playing or not. This is positive energy. When you can have this attitude toward competions, you start to win.

“I know that the only energy stronger than fear is love. To illustrate this point I use the following example with my students, most of whom are girls: If there is a fire in your house and your baby is inside, you will immediately try to save your baby. See…no fear! Love is stronger.

“Competitions are also motivational. I am from the South of France. We like the sun and are more laid back, more relaxed. I like life, so the only way for me to practice was to set goals, and competitions did that for me – 10 pieces for Munich, 15 pieces for something else, etc. Competitions were very good for me.

“Competitions also help to build repertoire and teach contestants how they will react in the face of fear and under pressure. I think that players need competition in order to build backgrounds and experience. Beyond that, competitions are essential for those who want to be signed to an agency or a recording contract. Although I don’t like it, the fact is that you need to win competitions for success.”

Teaching

Ferrandis teaches today at the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris, and says that “teaching is just a question of experience. The ability to teach is the result of having tried various approaches. Some work and some do not, so you just discard those approaches that do not work for you and keep those that do.

“I focus on the music when I teach. Mostly I want to be effective for the students. No nonesense. Students come from around the world in my classes. There are three or four students from the US and students from Japan, Korea, China, Italy – they come from so far, so I cannot cheat them. They have finished at their own colleges and are very good when they enter my class. They expect something special, and therefore I have to be very efficient and see that they receive what they came for.”

“I am a demanding teacher. I want students to understand that, for me, the most important thing is that they know what they want. If they know what they want musically, they will improve to the technical level necessary to produce it. They succeed not just because they practiced the assigned scales and etudes. Yes, the exercises are important for development, but the truth is that you have to know what you want to sound like. I ask them, ‘Do you want this color, to phrase this way, with this inflection? OK, show me that.” They get it, and they find the way to produce what they want. When you miss the mark technically, most of the time it is because you didn’t know what you wanted in the first place.”

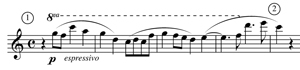

When asked about tone color, he said, “I have many stories. I was the flute soloist in an Orchestra Symphony Francais in Paris. Once Claudio Abbado came to conduct the Prokofiev Piano Concerto #3. You know it starts with clarinet pp, and the flute comes in afterwards playing the difficult theme:

“The Maestro was not happy because my high C was too loud. During a break in the rehearsal I looked at Abbado’s score. The clarinet is marked pp, but the flute is marked piano espressivo. I had been trying to play the solo in the color of the clarinet, but that was wrong, and my high C sounded tense. What Prokofiev wanted was the different colors of the two instruments. When I changed to the piano espressivo color, Abbado was pleased. Understanding the music saved me once again. The problem was not technical, as in ‘how do I play the high C softly enough,’ but musical!

“I’ve another funny story that demonstrates just how important a conductor can be in your musical life. When I was principal in my orchestra, guest conductors came, and generally they enjoyed my playing. Some even invited me to play a concerto. Once, a violinist friend called and asked me to play a Mozart flute quartet for a wedding. The bride had heard me play it at one of my concerts and enjoyed it. My friend told me that the mother of the bride wanted to listen to the rehearsal.

“Before the wedding, we played the entire Mozart D-Major flute quartet in a beautiful place in Paris for the bride’s family. What we did not know is that the bride’s parents were Mr. and Mrs. Lorin Maazel! Fortunately they both enjoyed my playing, and thanks to this wedding, Mrs. Maazel recommended me to the Lotos Club in New York.” In 1988 Ferrandis was elected Artist in Residence by the New York Lotos Club, an organization whose objectives are “to promote and develop literature, art, sculpture, music, architecture, journalism, drama, science, education and the learned professions, and to that end to encourage authors, artists, sculptors, architects, journalists, educators, scientists and members of the musical, dramatic, and learned professions in their work.”

Ferrandis does a fair amount of conducting and has his own ensemble, The Christopher Orchestra of Vilnius. He also conducts the St. Petersburg Camerata in Russia. As with many of his ventures, this one came about quite by accident. “To meet people is the most important thing to me. I was playing flute on a cruise with Vladimir Spivakov and the Virtuosos of Moscow string ensemble. I was supposed to play Mozart’s G-Major Concerto with them, and Spivakov suggested that I conduct as I played rather than having him conduct. “I was about to tell him that I had never conducted before, but he didn’t give me time to say it. So I went to the first rehearsal and conducted; the concert went well. After that concert the musicians went to Spivakov and said, ‘We have to invite this guy to Moscow to conduct.’ That’s how it all started. I had never conducted in my life. As you can imagine, I was very scared. Nobody knew it was my first concert conducting. After that, managers from the Russian Philharmonic invited me to fill in for their assistant conductor, who was unable to conduct several performances during that season. I was so surprised when they asked that I said, ‘Are you talking to me?’”

Ferrandis does a fair amount of conducting and has his own ensemble, The Christopher Orchestra of Vilnius. He also conducts the St. Petersburg Camerata in Russia. As with many of his ventures, this one came about quite by accident. “To meet people is the most important thing to me. I was playing flute on a cruise with Vladimir Spivakov and the Virtuosos of Moscow string ensemble. I was supposed to play Mozart’s G-Major Concerto with them, and Spivakov suggested that I conduct as I played rather than having him conduct. “I was about to tell him that I had never conducted before, but he didn’t give me time to say it. So I went to the first rehearsal and conducted; the concert went well. After that concert the musicians went to Spivakov and said, ‘We have to invite this guy to Moscow to conduct.’ That’s how it all started. I had never conducted in my life. As you can imagine, I was very scared. Nobody knew it was my first concert conducting. After that, managers from the Russian Philharmonic invited me to fill in for their assistant conductor, who was unable to conduct several performances during that season. I was so surprised when they asked that I said, ‘Are you talking to me?’”

The future holds many exciting projects for Ferrandis. He plans to continue conducting from the flute, and he is also very interested in transcribing works for the flute. “It is a tribute to the composer you transcribe. At the time of Mozart everybody transcribed everyone else’s works. Now some intellectual guys say you should not transcribe; this is stupid. Of course, there are some 20th-century works that do not transcribe well. Composers like Debussy knew exactly the timbre that they wanted, and changing those colors to a new instrument doesn’t work. But I often transcribe Classical and Romantic works. Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata, for instance, works very well for flute because the music itself is like a melody, a lieder. I really enjoy performing pieces that come from the vocal repertoire. We don’t have that much music for flute, so more and more I try to make transcriptions. I would like to publish these works. When the music is very flowing, we don’t think flute or violin, the music just comes to the flute. I would like to establish an arrangement with a publisher.”

Ferrandis also plans to perform with his brother, Bruno Ferrandis, who began his tenure as music director and conductor of California’s Santa Rosa Symphony Orchestra in 2006. Trained at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London as well as The Juilliard School, he has 20 years of conducting experience with some of the world’s great opera companies and orchestras of Europe and Asia. “We already have planned to perform the Mozart D-Major and Ibert Concertos together in Santa Rosa in May of 2012.”

Hopefully for us, more recordings are also in Ferrandis’ future. His most recent CD features the flute works of Yuko Uebayashi: Flute Concerto, Sonata for flute and piano, Suite for flute and cello, and “Au del du temps” for two flutes and piano. They are modern and Romantic, with a hint of Hollywood harmonies every now and again. You can hear short snippets of this CD and three others at jean.

ferrandis.free.fr/frameE.htm. At times his sound runs the range of vibrant and warm to fiery and agitated.