During my 30-year career as an educator, conductor, clinician, and adjudicator, I have probably seen well more than a thousand conductors leading ensembles in a wide variety of performances. While many of these performances have been outstanding and rewarding to observe, in some cases my attention was drawn to the physical gestures coming from the podium and the lack of clarity, detail, and musicality shown. A lack of independence in left hand gestures is a common problem. I see problems with physical gestures and left hand independence in my own students as well, particularly after they have worked in the public schools for a few years and developed a tendency to mirror most of their gestures.

In this article I address some of the most common difficulties that conducting students and conductors have with their gestures, and I also suggest some exercises to help resolve these difficulties.

Left Hand Independence

Conductors convey a great deal of information to the ensemble through gestures, and communication through gesture is much more effective when it is given independently of the baton hand. If the conductor has a habit of constant mirroring with the hands, this is a limitation because the left hand will be saying the same thing as the right hand, and the conductor will lose 50% of the chance to communicate with the ensemble. To correct this habit, conductors should spend some time each day retraining the muscles in the left hand to move independently.

The first exercise I recommend is taken from the Kenneth Phillips book Basic Techniques of Conducting, which I use with my undergraduate conducting class. In this exercise, which is called the Circle Drill, you pretend that there is a clock face in front of you, and you simply move your left hand around that clock face in a smooth, fluent, and circular motion, all while conducting 4/4 time in the right hand. The Phillips exercise does not say to do this, but I also like to have my students reverse the motion so that they practice moving counterclockwise as well. I also ask students to conduct both 3/4 and 2/4 time while they execute the drill. To add to the challenge, I may ask students random questions as they execute the drill. The students usually do not like this, but it is good practice because it helps students make the motions automatic without thinking about them. This circular motion practice does not necessarily have any direct musical application, but it is a good way to help students develop independence with the left hand.

A second drill that I use originates from another exercise in the same book (Phillips’s Basic Techniques), but I have expanded it a bit further. I call it the 3-1, 2-2, 1-3 exercise. While conducting 44 time in the baton hand, the students are asked to move their left hand outward horizontally for three beats and back in on beat 4. The students should repeat this motion three more times. Then we do the same motion on the vertical plane, and finally on the sagittal plane so that we are covering all three planes. The horizontal moves could be used for phrases within a measure such as dotted half/quarter, two half notes, or quarter/dotted half. The vertical moves could be used for crescendo and decrescendo as well as subito dynamics such as crescendo three beats and subito piano on beat four, crescendo two beats/diminuendo two beats, and subito forte on beat one followed by a three count diminuendo. The sagittal movement could be used for either phrase designation or dynamic designation, depending on the desired result. During this drill I will again ask random questions to my students as they execute the motion, which helps to make sure their brains are able to process stimuli while doing the moves automatically.

Gestures for Dynamic Contrast

When there is a lack of dynamic contrast shown in the right hand, bands tend to play too much in the mezzo and forte ranges, and conductors have a tendency to conduct too much in the same ranges. If we want our ensembles to play soft, we need to conduct soft. To help conductors understand and feel the softer dynamic ranges, I have them put their forearm flat on a table top or music stand and conduct the pattern using only the wrist down. This forces the conductor to restrict their dynamic motion to the wrist and fingers, and this shows conductors that they can indeed conduct at these soft dynamic levels. For mezzo levels, I instruct conductors to stand with their back against a wall and to put their upper arm flat against the wall.

This will force a conducting gesture that allows movement from only the elbow down, which should accurately reflect mezzo dynamic levels. For practicing forte and fortissimo gestures, I allow conductors to stand free of any restrictors and to conduct with a slight rotation of the shoulder joint to show the louder dynamic levels. Knowing how to conduct at louder levels is usually not a problem.

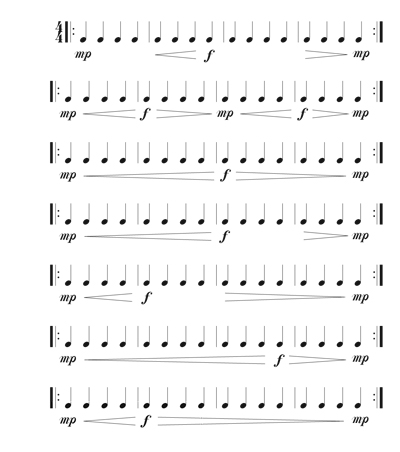

A lack of dynamic contour shown in the left hand is also a common problem. Although I usually see conductors showing some dynamic contours (crescendos, decrescendos, subitos) from the podium, conductors often do not indicate these musical nuances independently with the left hand, which is more effective than gestures that mirror the baton hand. A gesture will mean more and be more apparent to our ensemble members if they can see the gesture independent of the beat pattern in the right hand. You can be creative in developing different dynamic contours, but here are a few basic etudes to start with. Begin by moving the left hand only to show these various etudes, and then once they are on autopilot, add the baton hand back in, making sure that the size of the baton pattern is also representative of the intended dynamic.

Musically Expressive Gestures

A lack of musically expressive gestures in the left hand is also a common problem. When students have this difficulty I recommend that they practice simply not conducting with the baton hand while moving freely with left hand movements as they listen to recordings or rehearse their ensembles. This left-hand-only practice is an excellent exercise to do if you are sure the ensemble members can take responsibility for tempo and play on their own without you keeping time. During the exercise, show the music using the left hand only, and do not provide any sort of tempo gesture in your movement. Rather, the movements in the left hand should reflect only shape, contour, dynamic, line, or expression. The more you do this exercise the more comfortable you will be with making independent left hand movements, and you will be able to communicate much more with your group.

Conductors should also practice experimenting with primary and subordinate hand placements so that sometimes the right hand is primary and the left hand is subordinate, and sometimes the converse approach should be used. Whenever there is important information to convey with the left hand, it should be moved to the primary position while the baton hand becomes subordinate.

Subdivision in the Beat

The tendency to show subdivision in the beat is a dreaded problem. Of all of the challenges noted in this article, this is perhaps the most significant issue for conductors to be aware of and to work diligently to overcome. If not corrected, this issue can cause many problems for the ensemble, including lack of tempo consistency and clarity, as well as lack of musical line and expression. This problem also leads to an awkward visual representation of the music being performed.

This can be especially difficult to overcome because, in many cases, conductors are not even aware that they are doing it. A lack of awareness is especially common with conductors who have been teaching for some time, because their movements have become ingrained over the years.

A good first step in addressing this problem is for conductors to videotape themselves to see if they have this habit in their gesture. My conducting teacher used to refer to this as a check of perception versus reality. Conductors who have this problem of subdividing the beat often do not even know they are doing it. If the videotape shows that the conductor does this, here are a few exercises that I would recommend:

• Swimming pool. If possible, the conductor should spend some time in a swimming pool conducting various meters. While doing this, the conductor should pay special attention to the resistance, fluency, and motion that is required to move the hands. The benefit of practicing in the pool is that there can be no jagged movements or restrictions, and the resistance should disappear.

• Tenuto gesture. If a pool is not available, then simply reviewing and relearning the tenuto gesture will help. In this gesture there is a resistance of move-

ment from one beat to the next, and any breaking of this resistance will cause a disruption of flow.

• Painting the wall. With a paint brush in hand, the conductor should stand away from the wall just far enough so that the bristles still touch the wall and there is a nice bend in them. While in this position, the conductor should move either in a conducting pattern or in general motions, paying special attention to the flow of movement and resisting any urges to create a break in the flow.

• Ensemble member feedback. Input from the ensemble can be a great help to a conductor who is seeking to correct a habit. I used this technique during my doctorate work to break me of the habit of saying “I” during rehearsal. My tendency in rehearsals was always to say, “I want you to do this” or “I want this sound.” A wonderful conducting mentor and teacher of mine, Gary Hill, worked with me to understand that a conservatory ensemble is a collaborative environment and that I should instead use collaborative language such as “let’s do this” or “can we try to do this?” To break me of this habit, I simply had the front row hiss at me every time I used the word “I” in rehearsal. After a week of rehearsals sounding like a snake pit, my habit was resolved. This may seem rudimentary, but I think students love to see their teachers still learning and trying to improve. They will be happy to let you know when they see a subdivision in your pattern; trust me.

• Continued videotape reviews and evaluation. I think it is important for conductors to be lifelong learners and to understand that just as we want our programs to continue to grow and improve, we should want to grow and improve ourselves. I have a saying in our program at Pittsburg State that we are either growing or dying and there is no status quo. As inconvenient and painful as it may be to watch ourselves on videotape, videos do not lie. Watch yourself with a critical eye, and continue to improve your ability to communicate your musical intent through appropriate and meaningful gestures.

If indeed our job as conductors is to visually represent the music, then we need to be diligent in our self evaluation of our progress toward this goal. We should continually be monitoring our movements on the podium to make sure that we are clearly, efficiently, and effectively communicating the musical intent and ideas to our ensembles through our musical gesture. We should also be aware that our musical intentions are more clearly communicated by independent gestures shown in the left hand, which can be clearly read by the group, instead of by gestures that are mixed in with the information being given by the baton hand.

Even after thirty years of teaching and conducting, I still videotape every concert, not only to evaluate the quality of the musical performance by the ensemble, but also to evaluate my performance as a musical communicator from the podium. I challenge you to do the same.