Of all the idiosyncratic aspects of clarinet teaching and performance, pinky keys are perhaps the most confusing for students and teachers alike. There is a method to selecting left or right pinky for given notes on the clarinet, but even then there are disagreements among professional clarinetists. In this article, I break down my rationale for deciding what fingering to use.

Photo courtesy of Keller Middle School

When choosing fingerings for the clarinet, I follow several principles:

Alternate Pinky Fingers

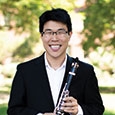

The clarinet’s many pinky keys allow performers to play most pinky notes using either the left or right pinky (sometimes both). This contrasts with the other woodwinds where the performer usually cannot play pinky notes with either hand. Flutists, oboists, and saxophonists can only play low C with the right pinky. To this end, a chain of successive pinky notes should alternate between right and left pinkies. When playing an E major arpeggio, clarinetists should play the chalumeau E with the left pinky, then use the right pinky to play chalumeau G#.

Similarly, with an E major scale, performers should play chalumeau E with the right pinky, then use the left pinky to play chalumeau F#, then right pinky for chalumeau G#.

Playing consecutive pinky notes on the same hand (often called sliding in reference to the pinky’s motion from one key to another) should be avoided as it is inaccurate and almost impossible to execute cleanly at fast tempos. I often tell students, “You paid for all those keys, so you might as well use them all.”

Keep Motion in One Hand

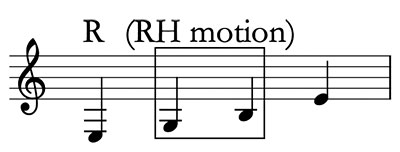

To paraphrase Occam’s razor, the simplest solution is often the best. If a passage does not have consecutive pinky notes, I recommend choosing the hand that moves next in the passage. Taking an F major arpeggio as an example, the clarinetist could play the chalumeau F with either the left pinky or the right pinky. I would opt for the right pinky since the right-hand ring finger also has to move to go to chalumeau A.

Using the left pinky would require both hands to move simultaneously, which invites blips between notes if the left and right hands are not perfectly synchronized. Similarly, the chalumeau E in an E minor arpeggio could be played with either the left pinky or the right pinky. I also recommend the right pinky in this situation, as the right-hand pointer and ring fingers will eventually have to move to go from chalumeau G to chalumeau B. This improves rhythmic evenness in rapid passages as the sense of tempo does not have transfer from both hands.

Use as Few Permutations as Possible

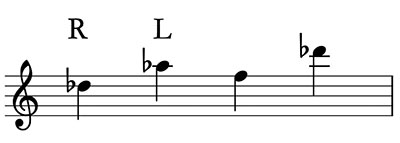

If both hands are equal according to the previous principles, I suggest looking a few measures after to see if one fingering becomes preferable later. If so, then I recommend using the fingering that will be preferable down the road to avoid confusion over lefts and rights. In an F major scale in thirds, the first clarion C could be played with either pinky, as the performer has to move both hands to move from throat A to clarion C and down to throat Bb. However, as the second clarion C should be played by the right pinky since that keeps the motion from clarion C to clarion E in one hand, I recommend the first clarion C also be played with the right pinky.

The hierarchy should be as follows: alternating pinky fingers takes precedence over keeping motion in one hand (sliding), while both should be prioritized over minimizing the number of finger permutations used.

Notes with Only One Option

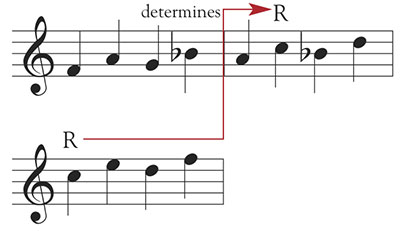

Compounding the issue of selecting pinky fingerings is that some notes can only be performed with either the right or left hand. Chalumeau Ab and clarion Eb can only be played with the right pinky, while chalumeau C# and clarion G# can only be played with the left pinky. Furthermore, most altissimo notes (altissimo D and higher) require the right pinky to depress the chalumeau Ab/clarion Eb key to be sufficiently high in pitch. If players encounter any of these notes in a series of consecutive pinky keys, they should mark L or R as appropriate above the note in question and alternate pinkies in the preceding notes.

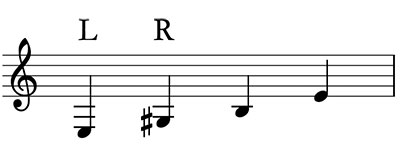

In a Bb major scale in thirds, students should play clarion C with the left pinky because it precedes a clarion Eb, which must be played with the right pinky.

Likewise, in a Db-major broken chord, the clarion Db must be played with the right pinky because the ensuing clarion Ab must be played with the left pinky.

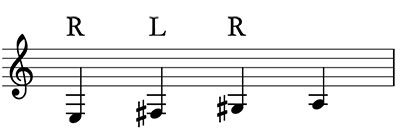

In the hypothetical C major thirds with octave displacement, the clarion C would be played with the left pinky because the altissimo E requires the right pinky.

.jpg)

The following excerpts present numerous fingering choices.

Solo and Ensemble Repertoire

The F# diminished arpeggio in m. 176 of Weber’s Concertino in Eb major, op. 26 is an excellent example of the importance of alternating pinky fingers.

The clarion Eb must be played with the right pinky, meaning the following clarion C should be played with the left pinky. At the commonly printed tempo of (dotted quarter note =100), it is nearly impossible to play this passage cleanly while sliding as I have heard many students valiantly but unsuccessfully attempt in auditions and festivals.

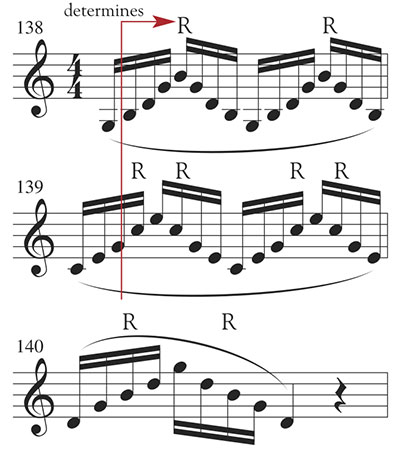

In mm. 138-140 from the first movement of Mozart’s Concerto in A major, K. 622, the clarinetist should exercise economy of motion by only using the right pinky for all clarion Bs and Cs.

Playing the clarion Cs in m. 139 with the right pinky means only the right hand is involved when moving to and from the clarion E. Likewise, playing the clarion Bs in m. 140 with the right pinky allows for the B-D-G-D-G motion to be contained to the right hand. While the clarion Bs in m. 138 could be played with either the right or left pinky alone, I recommend using the right pinky, as the left B lever is notorious for going out of adjustment, especially when subjected to the rigors of student handling and treatment. Since the right pinky will be used for the clarion Bs in m. 140, it is natural to use the same fingering in m. 138.

The triplet passage in mm. 27-28 from the second movement of Schumann’s Fantasiestücke, op. 73 is another excellent example of using as few permutations of fingers as possible. The clarinetist can finger the B-C sequence in m. 27 in multiple ways. Becayse the clarion C in m. 28 must be played by the right pinky (due to the clarion Eb later in the measure), I suggest playing the earlier clarion C in m. 27 with the right pinky as well. This reduces confusion over fingerings.

The clarinet solo at rehearsal letter I in the final movement of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, op. 35 (below) is quite the finger-bending passage at the customary tempo of 88 to the measure (quarter note or dotted quarter note). The clarion C#s in the first two phrases should be played with the right pinky to keep the Eb-D-C#-D-E series in the right hand, while the clarion Cs in the same phrases must be played with the left pinky as they come directly after clarion Eb (which must be played with the right pinky). In the last two phrases, the performer switches to playing the clarion C#s with the left pinky because they follow clarion Ebs, while the clarion Cs should be played with the right pinky to maintain right-hand exclusivity in the Eb-D-C-D-Eb sequence.

When Alternating Won’t Work

Inevitably, certain combinations of pinky notes sometimes prevent alternating pinkies. In these scenarios, one option is the dreaded slide discussed earlier. I prefer to slide my pinkies from physically higher keys to lower keys and from the top of the instrument to the bottom. One of these sliding scenarios is mm. 106–111 from the first movement of Brahms’s Sonata in F minor, op. 120 no. 1.

The clarion Eb in m. 109 must be played with the right pinky, meaning the clarion Db in m. 110 should be played with the left. The ensuing clarion Cb should then be played with the right, but the following clarion Eb in m. 111 must also be played with the right. One way out of this scenario is to slide from m. 109 to m. 110, with the right pinky sliding from the Eb key to the Db key – I mark these in my music with a thick line between noteheads.

If the passage features a sustained pitch, it is also possible to switch pinky fingers while a note is sustaining. In the context of the previous scenario by Brahms, the performer could initiate the clarion Db in m. 110 with the left pinky as expected, quickly add the right pinky, and then release the left pinky so the key is always depressed and there is no break in the tone. While not an option in faster rhythmic values, this is certainly viable on a sustained pitch.

Conclusion

There are many nuances that go into selecting clarinet fingerings. While much of this is up to the performer’s preferences, having a set methodology in place helps players who may not have previously reached this level of critical thinking. Combined with an awareness of all choices for pinky fingerings, these principles help clarinetists navigate technical passages with ease, allowing them to focus on making music.

Further Reading

Guy, Larry. Hand and Finger Development for Clarinetists. Stony Point, NY: Rivernote Press, 2007.

Ormand, Fred. Fundamentals for Fine Clarinet Playing. Lawrence, KS: Fred Ormand, 2017.

Paglialonga, Phillip O. Squeak Big: Practical Fundamentals for the Successful Clarinetist. Medina, NY: Imagine Music, 2015.