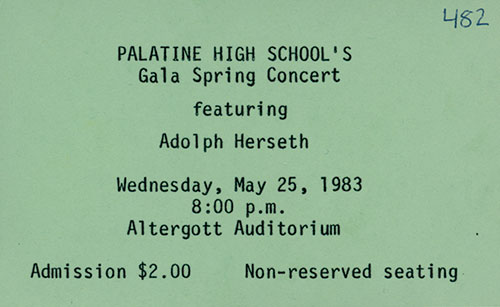

It happened right on stage in front of an audience of 500 parents and probably every serious trumpet teacher and student in the region. There he stood; a man considered to be the greatest orchestral trumpet player in the world – Adolph Herseth. Poised, confident, engaging the entire audience with his gaze, ready for his entrance. The Haydn Trumpet Concerto in E-flat Major had by then become his signature piece. In he came, and all were swept away on the musical journey to unfold.

One morning I was struggling to come up with a special year-end experience for my high school band students while saying to the choral director and assistant band director how great but unlikely it would be to have someone like Herseth perform. The choral director sat patiently listening to me carry on, but my assistant band director casually chimed in suggesting that I call him; he had his number in his musician’s union phone directory. There was no reason to back down. It would just take gathering up the courage to place the call.

My reverence for Adolph Herseth was long standing, and I was not alone. In 1948 at the age of 26 he was appointed principal trumpet of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and would remain in that position for an amazing 56 years of unparalleled devotion to his art. In no small measure he and his CSO colleagues set an unmatched standard of orchestral brass playing.

So, telephone in hand, my heart was pounding, panicking over what I would actually say if Herseth answered. One ring, two rings…and then there he was.

“Hello.”

“Hi, Mr. Herseth?”

“Yes.”

After clumsily introducing myself I managed, “I’m calling to ask if you might consider coming out to play with our high school band and choir on our spring concert?”

Without hesitation, “When is it?”

“M-May twenty-third,” I stammered.

“Hold on, let me check my book.” Clunk went the phone receiver, as I waited with bated breath.

Then, “Sure. I can do that.”

And there it was. Adolph Herseth, not only took my call, but had agreed.

Our concerts were collective department efforts, so the top Symphonic Band and Acapella Choir presented them jointly. It was decided to program not only the Haydn concerto, but also Norman Dello Joio’s Song of the Open Road for mixed chorus and solo trumpet, plus Awake the Trumpet’s Lofty Sound from George Frederick Handel’s oratorio Samson involving everyone – not only the choir and band, but two solo trumpets as well. Amazingly Herseth agreed to it all. An added bonus was to have our first chair trumpet play alongside our guest soloist on the Handel. What made that exceptional was that she was not only an excellent player, but had conquered the challenge of playing beautifully with a full mouth of braces.

Plans were made. Herseth would rehearse with us on the day of the concert. That morning, I was a bundle of nerves anticipating his arrival, praying that our intense rehearsing over many weeks was enough preparation to be worthy of providing the musical accompaniments. He arrived well before the rehearsal and immediately put me at ease with his warm yet business-like manner. The band filed onto the stage, and we warmed up and tuned. You could feel the excitement as well as tension as I introduced Mr. Herseth. The students applauded, he smiled, bowed and said that he was pleased to be with us. He was holding an unlacquered rather shabby-looking rotary valve trumpet on which to play the concerto. He raised it above his head so that everyone could see his horn and cracked, “See? This is what happens when you don’t take care of your instrument.” We all laughed realizing that this was an instrument appropriately chosen to be used for this piece. The rehearsal went well; balance was good and tempos were adjusted. He asked how I thought the concert would be attended and I told him that we were sold out; tickets were gone. With that, we were all set for the concert.

That evening Herseth entered to thunderous applause, bowed, nodded to me that he was ready, and off we went into the introduction. He made his initial entrance and that’s where the mini drama began – all completely unknown to me or the audience. The concerto ended, we shook hands, and I strode off into the wings following him. He turned to me and said, “That was good!” I was about to faint at the praise when he quickly added, “Now, being a good band director, I’m sure you’ll have a needle and thread in your desk drawer, right?”

“Why yes, as a matter of fact I do. Follow me.”

My office was only a few steps from the stage. As we sat down and I searched for the sewing kit, compliments of my dear wife Jane who was known as the uniform lady for the band, Herseth explained what had happened during the performance.

As the introduction neared the end, he raised his instrument and made his entrance. During the next solo break, he realized that his tux coat had come unbuttoned. He said he reached down to redo it, and the button, which had been hanging by a thread, came off in his hand. Ever so discreetly he slipped it in his side pocket, and no one seemed to notice. We had videoed the concert, and later, we saw it happen. All captured on tape. No drama. Just a display of being calm and cool no matter the circumstance.

Herseth calmly sewed his tux button back into place as we chatted during the choir performance. What an opportunity! The conversation moved from my love of the CSO to his recent visit to the eye doctor. It seemed that he needed to have a change in his eyeglass prescription. His doctor encouraged him to consider getting trifocals. All the better to see his music and the conductor he explained. With a twinkle in his eye, Herseth said, “Not interested. I don’t look at them anyway!” We chuckled, and with that it was time to return to the stage. Button problem solved.

The remainder of the concert went wonderfully. Afterwards, Herseth stayed to sign autographs and visit with students and parents. Back in the music office, there were warm goodbyes as Mr. and Mrs. Herseth departed for home. We directors were left with the most fantastic afterglow. Some exceptional music was made that night, and everyone talked about the concert for weeks afterward.

The lessons I learned were many and long-lasting.

Dream big. Summon the courage to identify and seek the best possible models for you and your students to emulate. I picked up that telephone months earlier placing the call to invite Mr. Herseth, quaking as I did

so but have thanked my lucky stars ever since.

Analyze the experiences you have and identify the things that you can learn from them; never be reluctant to change plans to best suit specific circumstances. I thought the Haydn concerto would be played on that rather scruffy looking horn, but it wasn’t. Mr. Herseth determined, perhaps based on the acoustics of the packed hall and other reasons, that his regular Bach trumpet would be the better choice. Also, standing right next to him as he played, I never really heard sound coming directly from his horn. Rather, it came from him. As odd as that seems, all I can say is that there was an absence of tongue/attack. His sounds were immediate. From that time forward I tried as much as I could to emphasize the elimination of hearing fixed percussive attacks in my student’s playing.

Have resources handy to address situations that may not be anticipated before they occur. Who would imagine needing a sewing kit at the ready for use by a guest artist in the middle of a performance? You just never know.

Provide your students with the best possible music and experiences; the results can have long lasting influence. To this day, many of my former students are patrons of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, play and sing in community and church groups all over the country, and best of all, have lingering fond memories of an evening when Bud came to play.