To develop a comprehensive percussion program and not just a great drumline, it is essential to work smarter during marching season. When we put the drums up in November, I want my percussionists to pick up xylophone mallets and take off running. The quad drums and the marimba should not be opposing forces. The response and in intensity are different, but the concept of precision and tone quality are still applicable.

Organization

It is beneficial for me to take a step back every year and reevaluate the entire percussion program. If you are graduating six seniors and you have 12 incoming freshmen it can change the entire dynamic of a group. I like to organize my thoughts and then brainstorm on short- and long-term goals. I wrote out five for this year.

Understand natural musical phrases and cadences. Although this is important for a drumline, it also has a great transfer of value over to the percussion ensemble music we play in spring.

Execute a relaxed natural stroke. I want students to get excellent sound production on all instruments without unnecessary tension.

Become a more cohesive percussion section. Last year the front ensemble and battery had separate warmups, and it was rare for the entire percussion section to get together. There were few opportunities to work as a full unit and talk about big-picture phrasing.

Focus on low-end dynamics. The aim is to have a good sound, lower at mezzo piano or softer. This takes precise rhythmic execution at lower stick heights.

Improve ensemble listening skills. This includes full-section work with a metronome both inside and out.

After discussing these with the staff and even some of the student leaders, I center everything I do around these goals. This includes the repertoire I choose and how I write the percussion book. It also factors into staff decisions. If I hire more staff, it is essential to consider whether I should look for people who work well with inexperienced players or people who have experience working at a high level of execution.

Optimization

Every time we rehearse, every rep we execute and every warmup we play should relate as much as possible to everything else we do. I have not played the traditional eight on a hand in at least ten or fifteen years; it is a stale exercise that generates no mental stimulus from the students. Many students can carry on a full conversation while playing eight on a hand because the phrasing is so easy.

A good alternative is to mix up the integers. Something like 8-8-7-9-8-7-9-8 still ends evenly but forces students to keep track every measure. It warms up both the body and the mind.

I work with all age groups, so I have developed tiers of warmups, which I label from A-F. An A-tier warmup, geared toward sixth graders, might simply be an eighth-note exercise they can work toward playing at a high level at varying tempos. Up a step, B-tier exercises, might incorporate bass drum splits (a separate part for each bass players) or tenor rounds (playing in a pattern around the tenors). C-tier starts introduce counterpoints and accent variation. A good example might be to have students add accents on the first and fifth eighth notes of every measure, which forces them to think harder about any sevens or nines I throw into eight-on-a-hand variations.

D-tier consists not only of single-hand work but also hand-to-hand exercises, such as sixteenth notes and triplets. To further increase difficulty, warmups could include rim shots and stick clicks. Depending on the group’s ability we can further extend the mental intensity of any warmup, or, if the group is inexperienced, we can limit things to A- and B-tier exercises.

Tiers can be combined. Right now, I have a killer bass line, but my snare drums are young and my quads are mid level. Thus, my quads are playing tier B, my bass drums are playing tier C, and my snares are playing tier A. This is good guidance for writing parts for warmups. It all works out musically and gives each section appropriate challenges.

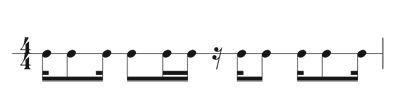

One of the places I teach is Baylor University. At the college level, there is limited time for section warmups when the band has to learn a show in two days. To make the most of the limited time I have, I write a warmup sequence that runs 21⁄2-3 minutes and covers as much as possible. It starts with unison eighth notes, then goes into a double beat pattern for practicing diddles.

This is followed by accent tap variations and rolls. By the end, students have physically and mentally warmed up everything they can without using much time.

I like running everything together because the average repetition of an exercise lasts roughly 12 seconds, but I have never played a movement of a marching show that was this short. During a marching show, everyone plays for anywhere from two to eight minutes without stopping, meaning students have to stay engaged for that long. If this is the length of a performance, then we do students no favors by playing for 12 seconds followed by a break. Part of matching warmups with performance is building mental endurance. If a show tune runs two minutes, there is no reason a warmup cannot last that long.

Planning the Week

Optimization also includes planning the entire high school percussion program, not just the drumline. Marching band music and concert band music should be viewed as tools to help one another. What happens in fall should support what happens in spring, and vice versa.

I see percussionists daily, and to avoid burnout I diversify my weekly daily schedule to give students some opportunities to step back let yesterday’s material soak in a little deeper while still keeping them engaged and learning. We still working on musical phrases and low-end dynamics, but we do so on something other than marching drums.

My week at my high school starts with what I call Masterclass Monday. There is no marching band work on Monday. We cover one concert band percussion instrument at a time in depth and apply it to other instruments when possible. For timpani, I point out the use of posture and horizontal and vertical movement and how that can be used with the quads.

Technique Tuesday can be anything from having students grab practice pads and work on double beats to learning to play congas and djembes to four-mallet grips. There is a marching rehearsal Tuesday morning, and the point we are at in the season does dictate our instrument choice sometimes.

Wednesday morning there is another marching rehearsal, and during class students break into sectionals. If one part fo the drumline has learned all of the music and cadences, they can get down to the nitty gritty of cleaning and working out details. A struggling section can practice things slowly. With six or seven divisions I rely a lot on outside staff or student leadership. This is an important culture to establish in any program.

Thursday is for full ensemble work. It is no coincidence that this comes after a day of technique and a day of sectionals. Thursday we put the big picture together.

The last school day of the week is called Finalize Friday. We iron out details, talk through the details and logistics of any weekend activities. Ideally we are prepared to the point that Friday can be slightly more relaxed.

Avoiding Burnout

I have a background in hand drums and drum circles. If my drumline students are not listening well to each other or the metronome, instead of just beating things into the ground with battery instruments, I take a day to have students pick up djembes, congas, and doumbeks and talk about rhythm. Students think it is fresh and that they are really learning about the djembe, but really we are focusing on listening skills. We play games that promote focused listening to individuals and listening skills across the ensemble. It is fun, it is fresh, and everything we do with the hand drums covers listening skills.

One game I like most is called Conversation. Everybody gets in a circle. I start out as leader so I can facilitate the game. I make eye contact with an individual and play a pattern. The student I look at has to play the same pattern. I move to the next student and play a different pattern. The catch to the game is that three flams in a row is the magic word. If I play three flams, everyone must respond, which means students have to stay engaged. A student who fails to respond is eliminated. The objective of the leader is to eliminate everyone. It becomes quite competitive. To add a dimension to the game, students can be given the freedom to respond however they like. This means that students can also invoke the magic word, forcing everyone to respond. The last student standing becomes the new leader. They enjoy getting each other out.

Unity

Unity refers to musical style. If warmups come from one person, the cadence a second, and the show music a third, it can cause difficulty for students. All the writers and arrangers may be outstanding percussionists, but differences in writing style or notation – even something like one person writing stickings in upper case and another in lower case – can slow students down. Diversity is good, but committing to one style during marching season makes rehearsals more efficient. The quads don’t need half their music written on the lines and half on the spaces. Unity of style alleviates questions.

Excellence in Everything

The culture I work to build with my percussionists is that we do not look down upon any particular thing we do as a drumline. We play in the stands at football games, have pep rallies at least once a week, and rehearse for 15 hours a week. I make a bigger than normal deal about achieving excellence in every component of what we do, because little things will add up to be big things. If we treat a pep rally as unimportant and play poorly, we are practicing bad habits. Eventually these things build up and trickle into marching and concert band performances. Even if the activity of the day is a sendoff for a state-bound team, it is important to use good technique, tone, and musicality to promote good habits and muscle memory.