As is the tradition of jazz music, students model their style and behavior after their teachers before developing a unique voice. Teachers can be partners with students and develop enhanced knowledge of jazz theory, aural skills, jazz history, and improvisation. For educators with little jazz experience, starting or building a program can seem challenging. However, it is helpful to remember that students will often experience the same challenges, frustration, and perhaps fear of the unknown. Teachers can model how to learn new concepts, start improvising, and appropriately handle making mistakes. Although it may be uncomfortable at times, we will more readily comprehend student mistakes and anticipate possible misunderstandings when we learn alongside them. Consider placing your students in a position to lead certain portions of the rehearsal to deepen their ensemble investment.

Rehearsal Time

Ideally, a jazz band should rehearse for 90 minutes twice a week, with each rehearsal broken into multiple activities. As teacher time, student schedules, and room availability will vary, it might be more helpful to consider activities as a percentage of rehearsal time.

First 90-Minute Rehearsal

Warmup: 15 minutes (16% of time)

Literature: 45 minutes (50%)

Jazz Theory: 15 minutes (17%)

Improvisation: 15 minutes (17%)

Second 90-Minute Rehearsal

Warmup: 15 minutes (16% of time)

Literature: 45 minutes (50%)

History Projects: 15 minutes (17%)

Improvisation: 15 minutes (17%)

Warming Up

Warming up a jazz band has commonalities and differences from a traditional rehearsal. Teachers must make sure to include idioms and vernacular specific to jazz during this time. For example, many directors begin a traditional class with long tone development. Consider using long tone exercises with chord progressions common to jazz. The example below is an orchestrated ii7-V7-I progression in order of the circle of fourths. Students can use such common progressions to learn about voice leading.

One example of a pre-written warmup is Andy Clark’s Five Minutes a Day. The first selection consists of long tones performed by wind instruments while the rhythm section provides a complementary style and the bassist plays a walking bass line. This warmup can also be transformed into an improvisation activity. While the rest of the sections perform their written parts, one performer can solo over the chord progression. This is a good way to give a student improv experience while keeping everyone participating. Treat your rhythm section players like you would in the context of any piece of literature: delegate comping rotations, work towards achieving a comprehensive style, organize chordal responsibilities, and make sure that every member of the section is contributing tastefully and sensitively.

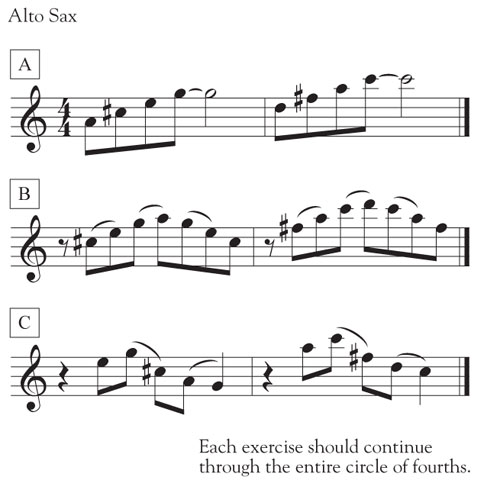

Warmups can also provide students experiences to develop an improvisation vocabulary. The example below illustrates an example of a saxophonist playing a dominant progression of chords.

In the first line, the dominant seventh chord is in root position, with each note articulated. The next line shows the chord in first inversion, on the and of beat one, and with a slur pattern. The third line is in second inversion, on beat two, and with a different slur pattern. This exercise will develop unconscious comfort performing chords in various inversions and on different parts of the beat. This can be the beginning of a vocabulary for improvisation. Each line should be performed using the entire circle of fourths.

Just as students learn major and minor scales, so jazz students should learn modal scales. At the minimum, students should be familiar with blues, pentatonic, Mixolydian, and Dorian scales. However, diminished and Lydian-dominant scales are also beneficial. Consider making worksheets to fit the needs of your program. Include potential slur and articulation patterns and make sure to warm up on scales found in the literature you are performing that class. Later when students improvise, they will be familiar with scalar options appropriate for the selected piece.

Jazz contains unique interpretations of articulations that students must learn in order to perform with authentic style. Students will benefit from articulation warmups to reinforce these alterative interpretations. One effective method is to create a series of short vamps (repeated passages) on a set rhythm and pitch. Students focus on performing the exact same note and rhythm with unified articulation. When students understand how to interpret articulations, they can transfer the knowledge to literature and your rehearsal time will be more effective. When addressing articulation phrases with your drumset player, pay close attention to their choices in voicings: short articulations can be voiced on snare drum, closed hi-hat, or a cymbal choke, whereas articulations that require a longer duration may be coupled with sustained cymbal crashes, bass drum hits, or open hi-hat splashes.

One final warmup idea is a variant on dividing an ensemble into three groups and playing a Bb scale in half notes with staggered entrances. Have the jazz band divide into four groups. This will introduce students to the sound of major, minor, and half-diminished seventh chords.

Concert Literature

The best approach to this daunting task is to pass out far more literature than students can perform in a given year. We will give students a binder with around 30 songs of varying difficulty, styles, tempi, rhythmic complexity, and increasing instrumental range. Devote the first few weeks of classes to reading through as much literature as possible. This will help gauge student ability and interest – and something that might be too challenging at the start of school could be a great choice for a final concert.

A typical jazz band concert includes around six tunes. Styles might include Latin, bossa nova, swing, big band, a ballad, and a pop tune. Ideally, at least three of the pieces should highlight student solos, whether written or improvised. Written solos are helpful for encouraging performance success, especially for younger bands. Use this as a scaffolding technique; have students learn the written solo but eventually wean themselves off by replacing segments with improvised lines and phrases.

For less experienced groups, leave solos unassigned until closer to the concert. This encourages all students to practice and audition for the opportunity. If you repeat pieces in various performances, you might find that soloists change with increased student motivation. When solos are open to audition, more students are inspired to pursue the challenge and learn something they would not have otherwise.

Literature Rehearsal and Sequencing

Rehearsing literature in a jazz ensemble requires the same scrutiny as any other performance group. Key elements include taking time to purposefully assign, copy, and distribute parts; developing a warmup/theory/history lesson that has direct stylistic congruence to your piece; anticipating potential problem areas, tutti sections, form structure, and solo moments; and ensuring that you have reviewed and accounted for the use of mutes, doubles, auxiliary instruments, extended techniques, and rhythm section instrument filters such as guitar distortion, electric organ, and electric or acoustic bass.

Because of the varying style and articulation found in jazz literature, young ensembles will be best served focusing on one or two pieces per rehearsal. This philosophy helps reinforce and solidify a chart’s style and character. As the concert nears, increase the number of pieces rehearsed to help simulate the reality of performing six tunes back to back. As you navigate a tune for the first time, start with big picture objectives applicable to all ensemble members. Rehearse segments that clearly represent the style and form of the piece. Use these teaching moments to point out articulation choices, call and response roles, and assign students to listen to specific members of the ensemble. In time, narrow the teaching sequences to more detailed, isolated phrases.

Jazz Theory

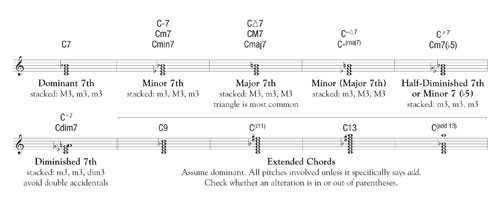

Teaching jazz theory is similar to traditional music theory. The biggest difference lies in a few basic assumptions and the use of symbols. In jazz music, chords written with just a letter (i.e. Eb) are assumed to have a dominant 7th attached to them unless otherwise specified, as in Eb(no7). Adding a triangle to a chord means you have added a major 7th. Adding a dash to a chord means you have added a minor seventh. The circle with or without a slash indicates half-diminished and fully diminished chords respectively. The example below includes examples of the above as well as the meaning of combinations of symbols. While interpreting the symbols may be challenging at first, both teacher and student will gain comfort over time.

Sevenths, ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths should be introduced both as block chords and arpeggios. Certain chords are easier to remember than others once students are able to appropriately label a familiar sound. For example, a minor-major chord (which means a minor base with a major seventh, i.e. C-Eb-G-B) might seem intimidating to learn, but once the term is attached to a sound – students are likely to recognize the chord made famous in many James Bond movies. Teachers can develop their own jazz aural skills alongside students. When students learn to recognize types of chords, they transfer those enhanced listening skills to their ensemble literature and can make increasingly informed musical choices.

History of Jazz

A project-based approach to teaching jazz history pays dividends. Research and assign every student in your ensemble a famous musician who plays their instrument. Either provide them a CD or playlist of that musician performing or give them an assignment to create a list. If you allow students to create their own playlist, require the inclusion of full ensemble pieces and solo tunes. Give each student a transcription of a solo by that performer (many transcription book resources are available) to learn. On their assigned day to present, the student gives a history of the jazz style and era of their performer as well as a brief biography highlighting specific performances. At the conclusion of their presentation, they should perform the transcribed solo. Typically, two students can present each jazz history day.

Part of an authentic jazz experience includes learning the importance and value of transcriptions. This is an excellent opportunity to emphasize the value of aural skills development, introduce dictation, and demonstrate the transformative nature of jazz over time. As a primarily aural art, transcriptions are of greater value than students may realize. As your ensemble grows and develops, consider providing transcription activities and slowly progressing to more challenging assignments.

Call and Response

Call and response is a historical pillar of jazz. This technique of engagement can be traced all the way back to West African musical traditions. Although Western classical musicians might be most familiar with this practice as a performance method or compositional tool, in its original African form, call and response is founded upon social interactions. Teachers play a crucial and interactive role with students during this portion of the rehearsal.

Learning the style of jazz is often associated with acquiring a new language. Numerous languages around the world are absorbed through listening, mimicking, and eventually reading. These three tenets work well within the jazz ensemble. For example, a teacher can simplify a single rhythmic motif, with specific articulations, to be played on a concert F without notation. The ensemble listens to this motif and echoes it back in unison. The ensemble is listening and imitating without potential distractions such as range, written music, multiple pitches, harmony, and rhythmic counterpoint. Remember, at this point our primary focus is listening and mimicking. As students gain confidence responding, add additional elements to the equation, including varied pitches and rhythms, advanced articulations, written notation, extended phrase durations, and changing tempo and dynamics.

Although most of the rhythm section has the facility to participate in this exercise, a drummer cannot play melodies on the drumset. Embrace this as a challenge. Have drummers keep steady quarters, eighths, or a swing pattern on the ride cymbal. As the teacher provides the call, the drummer maintains a steady beat on the ride while mimicking the articulations and style with the other hand and the feet. This practice is a fantastic introduction to comping. Further exploration with call and response might include having your rhythm section play a repeating twelve-bar blues progression while the teacher and winds trade figures or having a student lead the interaction. Call and response is about learning the language of jazz and engaging with your students.

.jpg)

Curricular Resources

There are numerous resources for teaching students how to improvise. One good choice is the Aebersold Play-A-Long books. These well-known collections are full of tunes with a head (also called a melody) followed by improvisation sections notated using jazz symbols. They are divided into parts by transposition type and include play-along tracks. These books are great for students familiar with jazz symbols who have developed an improvisation vocabulary of rhythm and tonal patterns. Teachers can have the entire class play the head, then several students perform the solo selection, then everyone play the head again. However, if the students are unfamiliar with the meaning of jazz theory symbols, this book will be a challenge.

Another worthy book is Developing Musicianship Through Improvisation, which was researched and written by several professors at the Eastman School of Music. This three-volume series contains improvisation units consisting of repertoire, patterns and progressions, improvising melodic phrases, seven sequential skills of improvisation, reading and writing solos, and aurally learning and transcribing solos. These books also include play-along recordings. Educators who prefer a sequential curriculum to teach improvisation may benefit from the series.

Jamming with Students

One of the most effective ways of encouraging students to improvise and experiment musically is to jam with them. Students love to perform with their teachers. In one of our classrooms, students became so invested in jamming with the teacher that increasingly large groups of students came during their lunch. Soon the noon hour became daily improv time, with students coming and going as they wished. Even students who had initially hesitated to perform before their colleagues were drawn to free improv sessions. In reflecting with them afterwards, their most frequent reason for coming to lunch jams was that they enjoyed performing with their teacher.

Final Thoughts

Students experience numerous benefits when performing jazz and can increase and diversify their musical knowledge. In addition, the study of jazz history, its cultural origins, and social influences are perfect windows into interdisciplinary projects and presentations.

Jazz ensembles are also manageable and popular ambassadors for recruiting, community outreach, playing at school board meetings, and performing at other school-related events. Even without expertise in the idiom, approaching the subject as a teacher-learner will contribute to a more communal, equitable learning environment and set a great example for student growth.