Percussionist Timothy Adams, Jr. has pursued a musical journey of dazzling variety. He became Chairman of the Percussion Department at the University of Georgia in 2010 after performing for 15 years as principal timpanist in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He has also been a member of the Indianapolis Symphony, Florida Philharmonic, and Canton Symphony and taught during the summer at Brevard Music Center and the Eastern Music Festival. Adams earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Cleveland Institute of Music. He has performed on movie soundtracks, the popular PBS show Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, and in the 1980s rock band Exotic Birds, which appeared frequently on MTV and VH1. Adams credits his success in the music business to the high standards set by teachers in his formative years, starting with his father, a long-time band director. He recalls: “I was never given any leeway on playing perfectly in time with a good sound. Even in the 4th grade, I was expected to approach the music as if I was a seasoned, 30-year orchestra musician.” Adams tries to teach his students with the same high standards that have propelled him to such success in music.

What lessons from your teachers have helped you the most over the years?

Bill Wilder, who still plays in the Atlanta Symphony, taught me from 4th grade through 12th grade. He really showed me how to play and think about music. Even when I was in 4th or 5th grade, he never gave me the answers directly. He might walk out of the room and tell me that I should figure out a particular problem by the time he came back. I learned from him how to teach myself. If I had resolved the problem, great. If not, he showed me how it went. On rhythm, he was adamant about perfection.

I studied everything with Bill Wilder – snare drum, mallets, drumset, and timpani. We did an excessive amount of ear training on timpani for a junior high or high school student. He taught me attention to detail on sound and touch. We did a lot of reading and worked on complex rhythms. Sometimes, I look at my old books and the dates certain exercises were assigned. I cannot believe some of the things I was playing in the 7th grade, but I did not know it was particularly difficult. He never presented the material as if it was hard.

I also studied with Paul Yancich during my junior and senior year, then the timpanist with the Atlanta Symphony. I started playing as an extra in the Atlanta Symphony as a senior in high school thanks to Bill Wilder, and I made my first professional recording with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, thanks to Paul Yancich. It was a terrific experience. I remember sitting in a concert that included Mahler 5 and Don Juan. I happened to look up at Paul during this G roll in Don Juan and thought, “I want to sound like that guy.”

I asked where he went to school, and he told me the Cleveland Institute of Music. I decided that if I could sound like him, this is where I wanted to go to school. My dad drove me around to visit five schools I was interested in during the summer before my senior year . I met percussion teachers or administrators at each school. Cloyd Duff in Cleveland was the person who resonated the most with me. He invited me and my dad to his house. He was very engaging, and I left knowing I wanted to study with him. I studied with Cloyd Duff for two years, and he really showed me how all percussion instruments sound, not just timpani. That knowledge has informed my career in music from the day I set foot in the Cleveland Institute of Music. The beautiful thing about sound production, expressiveness, and attention to detail is that it bleeds into every genre of music and every instrument I have touched.

I studied next with Richard Weiner, principal percussionist of the Cleveland Orchestra. He is a terrific musician and technician. I learned from him how to play in an orchestra and how to move sound and phrases away from me. He helped me to think always about the audience and what they hear. I studied again with Paul Yancich again in my last year of college after he became timpanist of the Cleveland Orchestra. These people changed my life and remain big influences

How did your rigorous early ear training help in college?

The ear training exercises with Bill Wilder were extremely advanced. He would play a note and have me sing multiple intervals above and below the note. Then he played random pitches in random ranges of the piano and have me sing them back. He also played F major scale going up, and I would have to sing Ab major going down. He would not let up if my singing was off. I had no idea how much this would help when I went to college. Even in junior high I never had trouble tuning timpani because my ears were strong because of the work we did. We practiced ear training two or three times a month for years.

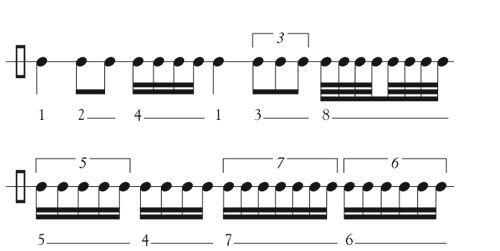

He took an equally tough approach with rhythm. I would set the metronome at q = 60 and just play numbers from the entire phone book. Let’s say your number was 124-138-5476. One would be a quarter note, two would be two eighth notes, four would be four sixteenth notes, three would be a triplet, eight would be thirty-second notes, and so on.

Wilder explained how rhythms were clearly delineated by the first two notes of each figure. This exercise trains players to start and stop and never crush or drag rhythms. It works perfectly. I knew how to work out rhythms in complicated parts. I would never have to guess. That gives you a lot of security in an ensemble. People around you trust what you play because it sounds solid and secure from the beginning to the end. Nothing wavers in the middle.

Wilder was adamant about playing to the downbeat of the next beat, putting the dotted line between the first two notes and then the second note of the second figure becomes a new rhythm. That training prepared me for college so that all I had to do was read the new literature.

What are the secrets for moving sound and projecting it to the audience?

With timpani, at the moment of impact you lift the mallet off the head, and that makes the sound move. If you keep that concept whether the music is loud, soft, fast, or slow, the timpani always sounds crystal clear. You achieve that with a rotating wrist motion. I use a thumbs-up French type of grip and at the moment of impact, I naturally bring the stick back and have some natural rebound, but I make sure that the mallet does not stay on the head. That makes the sound move.

Also, any small note figure, say an 8th note and two 16ths, the 16ths would be the small note value of that rhythm and should be emphasized. It sounds a little bit uneven to the player, but by the time it gets to the audience, it is crystal clear. This approach is very good for the ensemble, but just is not done by a lot of players. A band director can insist on clarity from the instrument. You only get that by lifting the mallet and coming off the head. Otherwise, the sound is lazy and cumbersome.

All mallet instruments should be played with the same wrist motion. Once again, the sound comes off the instrument, and the grip is as light as possible so you don’t drop the stick. You want the stick to vibrate because the tighter you grip it the more the stick is choked, and then the sound is choked. The same thing applies on snare drum and timpani. You always want to lift off the head. Anybody who plays a sport that requires a stick, like golf or tennis, understands the importance of grip and touch. The pressure has to be as relaxed as possible at the moment of impact, so the club can move the ball at the right speed and trajectory.

The stroke for bass drum or timpani is similar to casting a fishing rod or turning a doorknob – that kind of wrist rotation in the forearm allows the stick to come off naturally. If you hold the stick and move your entire arm, all of sudden the mallet becomes that long and doesn’t move efficiently.

How do you play percussion instruments in a melodic way?

Melody is a tricky word that can confuse people. In general, most musicians do not think of percussion instruments as melodic. You can play melodically even on one note. If the snare drum is tuned properly, you can hear the pitch that resonates. If you are playing in a natural, relaxed way, and your roll has a sustained sound resembling a singer or a wind player, the snare drum suddenly sounds melodic. If everything works properly, the hands are perfectly even, and the rhythm matches what is going on in the ensemble, then the snare becomes melodic. Being melodic doesn’t always mean playing an instrument that plays pitches that you can write out in treble clef or bass clef. Some of the prettiest melodic playing that I have heard is on drumset or an ensemble of African drummers.

What are some of the most difficult things for a percussionist to do well?

It is tough to be an expert on every instrument. It is the most frustrating profession on the planet because there are experts who play xylophone or marimba or drumset or timpani. I think the key is to accept emotionally the things that you are great at and accept the things that you do not play well.

As a percussionist when you are in school or on the way to becoming a professional, your expectations should be that you work hard to play great. It take a lot of time. It is not the same as playing one instrument where if you could practice three hours a day and become very good at it. With percussion, it is just not possible. If you play one hour of snare drum, one hour of xylophone, and one hour of marimba, one hour of timpani, one hour of accessories, we are at five hours and haven’t touched drumset or hand drums. It is very daunting.

You have to have a certain disposition and fearlessness that those instruments do not intimidate you, that’s just what we do. I firmly believe that the foundation of being a great percussionist is being a great snare drummer because you have to have your large and, most importantly, your small muscle groups extremely developed, and that transfers to every instrument.

What advice would you give to band directors to improve their percussion section?

What advice would you give to band directors to improve their percussion section?

I find it disappointing that band directors speak to the percussionists differently than they speak to the flutists. They will tell the flutes to play more legato and more connected, and the percussion section will be told not to play so loudly. If the director spoke to the percussion section with the same articulation instructions, the percussionists would have a chance to develop. It doesn’t matter whether the percussionists are playing sixteenth notes or flams, their contributions can be melodic and beautiful. Their development is based on the director’s commitment to treat the percussionists like every other instrument in the ensemble. It is very easy to keep percussionists engaged. Just talk to them. Expect the same from them as every other musician.

A woodblock can be staccato, legato, or sostenuto; it can do anything. That challenges a percussionist to figure out how to make the woodblock produce all of these sounds. It is the director’s job to go and ask questions of a professional percussionist for specifics how to make the section play better. When my father was a band director, his flutes were weak, so he took flute lessons from the principal flutist of the Atlanta Symphony. That’s what a real educator does. They want to make sure that every player in their ensemble gets the care that the music deserves.

What are some ways to get a good sound out of crash cymbals?

Both cymbals should vibrate the same way. Some band directors teach students to hold one cymbal stationary and strike with the other at an angle. That produces either an air pocket because the cymbals stick at the moment of impact or a very harsh sound. Next, young players are told to hold the cymbals up. I do not know why they are told to do this because it makes the cymbals stop vibrating immediately. The key is to make sure that both cymbals strike at the same time and velocity. Then, you will ensure that the plates vibrate the same.

I bring my left hand up and my right hand down, with the edges of the cymbals about an inch and a half apart, making contact at 45°. I try to get an open, flam sound. If it is stuck properly, you get a chaaa-chaaa-chaaa sound every single time. I once asked Joe Adato, the long-time cymbal player for the Cleveland Orchestra, to explain what he thinks of when he crashes. He said, “Kid, it’s like two locomotives crashing together. You understand?” I told him I understood. The same concept applies when you crash softly. The only difference is that the edges are about a half-inch apart. The flam on the front

end makes the sound expressive. The instrument is struck on time but it has more nuance. Cymbals are one of the most musical instruments in the percussion section. You can do so much with cymbals it is unbelieveable. People have made careers playing cymbals in orchestras or military bands.

What should young players know about the difficulties of becoming a professional player?

They do not realize the amount of time it requires. Although technology has changed in recent years, and access to information is immediate, becoming a musician is still a slow process. It takes years of practice and patience. As a teacher, I spend most of the time convincing students to practice. That is required to play well.

Sometimes the standards for percussionists are too low. A tremendous amount of detail work is necessary for every aspect of each instrument. With timpani you want to produce a great sound that is in tune. With snare drum, make sure you have impeccable rhythm, a terrific roll, and a great sound. Mallets demand great sound and extreme accuracy. You have to practice, practice, practice.

Some young players are praised for their success on one percussion instrument and become the specialist in their band on that instrument, never developing their skills on other instruments. This must be avoided at all costs.

What advice would you give a high school jazz director to help young drummers?

It is important for the drummer to listen to recordings in the style the band is playing. Many young jazz drummers play poorly because they lack experience with the appropriate style. I recently worked with a student who wanted to learn drumset. We started with swing, and I asked her to listen to So What from the Miles Davis Kind of Blue album ten times a day for the next seven days. She listened to it 70 times and sounded terrific after a week, picking up nuances we had not addressed. You can always use great recordings to teach the swing tradition. If you inundate students with listening, they can make surprising progress.

Some of my students play in jazz band, and periodically I will walk in to observe their performance. I might tell them that they are playing as if they are playing in a small group. Their playing is too interesting with too many notes. The drummer’s role is to swing and keep time. I might recommend a recording and encourage them to come back and try something different based on their study. When I return a couple weeks later, the band sounds better.

What do you tell students who want to pursue a life in music?

Being a musician can inform your life in a way that no other art form can match. If a student wants to pursue percussion, even if not as a career, it teaches valuable lessons about discipline, versatility, and working with other people in the section. As percussionists, we do not have instruments on our face, and have to get along with people and to share instruments. There is so much to learn as a percussionist that can help your life in a way that is not musical. It is tremendous. If you embark on a life as a percussionist, the satisfaction you get from playing a multitude of instruments is something that words can’t express.

Growing up with a father who was a band director, what is the biggest lesson you have carried with you from him?

We started teaching summer band camps together when I was in high school. He always reminded me, “you should teach life, not music.” That made a big impression on me. It wasn’t just his mantra; it was in his DNA. Now, I know that is true because I see so many of his former students come back and say how he affected their lives. Music is the second thing that comes out of their mouths. The first thing they say is that he really taught them discipline, understanding, and compassion for others. At some point I hope to reach a certain age where my students say that about me.

Timothy Adams Jr. was born and raised in Covington, Georgia. His performance career has taken him to major concert halls around the world in Europe, Australia, and Asia. He endorses Pearl/Adams Percussion, Zildjian Cymbals, Evans Drum Heads, Freer Percussion, and Mike Balter Mallets.