![]()

J.M. Burger, Straussburg c.1900 conical Boehm

I will admit from the outset that I have been a lifelong collector of things – rocks, stamps, shells, books, engravings, music – my family even accused me of having a wire collection. In recent years I have focused my collecting desires on flutes, and this has been extremely rewarding. I thought I would pass on both some reflections on flute collecting and some advice to those who may also find this an interesting undertaking.

As a performer on historical flutes, the collecting of these instruments comes rather naturally to me. Over a period of 40 years, I have acquired various flutes of historical interest, but I did not begin collecting in a serious, organized, manner until five years ago. Although my main interest is Baroque music, 18th-century instruments are considerably more rare and expensive than 19th-century ones, so these days collecting 19th-century flutes is more common.

nach Meyer, Germany, simple system 10-key

19th-Century Flutes

A few years ago, I became interested in both the music and instruments of the 19th century. As is usually the case, the more I collected and studied the instruments and repertoire of the period, the more fascinated I became. I found many instruments available and discovered that the flute repertoire was huge, interesting, and virtually unknown.

My collection started off in a rather unfocused manner, which is a reasonable way to get one’s feet wet. I simply looked for good deals on what appeared to be interesting flutes from Germany, Vienna, France, England, and America. As one starts investigating 19th-century flutes, it is immediately apparent that there are virtually an infinite number of different styles of flutes and different models within those styles. Even just collecting within a single country presents a huge number of options, both with simple-system and Boehm flutes. Compared to the modern flute of today, the selection that a flute player could choose from in the 19th century was huge.

In the 19th-century flutes were very nationalistic items. Each country had its own designs and preferences both in terms of desired tone and tuning but also the mechanics and even materials used in the making of flutes. These days flutists are broadening their interests slightly through the resurgence of the modern wooden Boehm flute, but in the 19th century one had a choice of two different types of Boehm flute, either conical or cylindrical, with the conical ones being wood and the cylindrical one available in a variety of woods and metals. Simple system flutes could vary from one key to 13 or more. Many hybrid instruments were also made.

D’Almaine & Co. , Late Goulding & D’Almaine, Soho Square, London, c.1840, 8-key simple system

Flutes of Different Countries

English flutists had a strong desire for a very big sound (thanks in part to the popularity of flutist Charles Nicholson). Their instruments had larger embouchure holes and tone holes in comparison to other countries. This caused various things to happen. One of the biggest was that the flutes were designed to be played using the keys for the various accidentals and generally not allowing the cross-fingerings in use on flutes from the 18th century and still available in some flutes in the 19th. The 8-key flute was standard throughout most of the century and was not eclipsed by the Boehm flute probably until the 20th century. There are many of these English flutes available today.

Viennese flutes were particularly fine, and one can still find flutes of the type that Beethoven would have known. These flutes are more difficult to acquire and command higher prices. They are quite sophisticated and often had a B-foot (in a 9-key version). Italian flutes were initially based on the Viennese designs of Koch and Ziegler, but they eventually found their own path and made many fine instruments. They are not as common in the US.

Germany also produced many different models of flutes that included very sophisticated designs of all types as well as instruments like the nach Meyer flutes, which were produced in great numbers with many being exported to the US and elsewhere. The United States had an extremely busy flute scene with companies like Firth, Hall, and Pond that produced large numbers of flutes of varying quality. Most of the larger flute companies made inexpensive (and often not very good) instruments as well as fine concert and presentation flutes.

My own collecting focus is on French flutes that come in many different designs from 1-key to 11-keys and encompassing superb flutes of both the Boehm conical and cylindrical models. Pricing for these flutes tends to be reasonable, especially as they are likely to play well. The French had a tonal model which emphasized sweetness over volume.

Firth, Hall & Pond, NY, simple system 1-key

Value of Old Instruments for Flutists

I have noticed that many top collectors of flutes are not actually flutists themselves, but are interested in the history, technology, and beauty of the historical flutes. On the other end of the spectrum are people like myself who really want to experience playing these instruments together with the music they were made to perform. One learns a tremendous amount from playing music on the flutes the music was written for. Even if one is not eventually going to perform the work on an old flute, it is a wonderful experience to get a feel for things the flutes do very well and those that they do not.

As an example, although all flutes have a wide dynamic range, early flutes were usually quite a bit softer than modern flutes. In particular, very loud, hard edged playing in the lower register was not a technique that could be used on these flutes. It was clear that for 18th- and 19th-century composers, a scale or arpeggio going up was going to yield a crescendo and probably an increase in energy. The modern flute and modern musical practice tends to want to even out such figures and eliminates an important part of what the musical phrase or figure was designed to accomplish. This phrase shaping is quite natural on most old flutes.

Firth & Son, NY, c.1863-64, simple system 8-key

Other Characteristics of 19th Century Flutes

A common question is whether a one-key flute from the 19th century will be just like a Baroque flute and suitable for playing 18th-century music. Generally, the answer is no. While the fingerings are basically the same, flutes in the 19th century were designed to favor the high register, while the earlier ones focused on the lower two octaves. The pitch of a 19th-century flute is different as are aspects of the tuning and desired tone quality. These factors create a very different sound and feel.

Pitch is one of the first problems that people run into when starting to collect flutes. In more cases than not, A=440 was not really the pitch the instruments were intended to be played at. The most common 19th-century pitch was probably A=435 in the mid-century or A=430 at the start of the 1800s. There were quite a few higher pitches used as well. Many English flutes were made at a pitch, almost, but not quite, a half step around A=440. Many French and German flutes were made at A=448 (including flutes of the foremost makers such as Louis Lot.) Sometimes you can find flutes that will play at A=440 if they are all the way pushed in, but they were usually designed to play lower. Many of the silver flutes of the famous French makers have been cut down to make them work properly at today’s pitch. To get the maximum potential from a flute, you should play it at the intended pitch and not try to force it to another pitch or alter the instrument from its original condition. Obviously, there are practical problems with this as with modern instruments people are pretty well stuck in the A=440-442 range. It is important to recognize that the pitch of an instrument makes a big difference in the tonal quality intended for the instrument. There is a large difference between a flute designed for A=430 (dark and rich sounding), and a flute at A=446 (clear and bright). These differences are one of the things that make playing on these flutes so interesting.

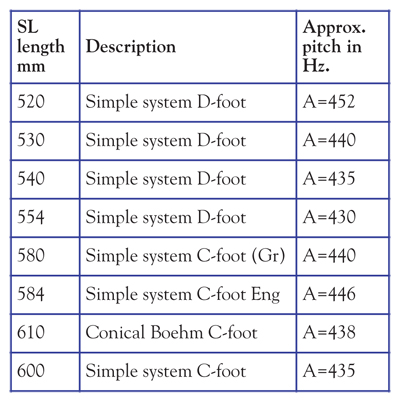

Sounding Length (SL) is the measurement from the middle of the embouchure to the end of the foot joint. The SL is the best way to make a guess at the intended pitch of a particular flute if you cannot test the instrument yourself. It does not work 100% of the time, but it is the best way to get an idea without playing the instruments.

Here are a few examples:

Important note: If the flute does not have a tuning slide, push everything all the way in. If the flute does have a tuning slide, pull it out 7 mm.

Buying an Old Flute

Proceed carefully when you buy an old flute. By far the largest market is through eBay. Traditional auction houses sell an occasional old flute, but they are generally in the more expensive price range. Flutes are still found in antique stores or even flea markets, especially in Europe. There are some complexities to purchasing on eBay. First and foremost, sellers often know nothing about the instruments they are selling. Getting a fix on the condition is particularly difficult and finding out things like pitch are pretty much impossible. One has to become very good at examining the limited photographs provided to try to see what may be wrong with the instruments and even if all the parts are there. The sellers often just don’t know. There is a positive side to this as well, as sometimes you can find bargains on fairly valuable instruments. There are usually other savvy buyers, so you may still have to compete to get the flute.

Another problem for inexperienced buyers is that the flutes for sale are usually the most plentiful and cheap instruments of the era. The most common of these are nach Meyer flutes. They are 19th- or 20th-Century flutes copied from the original designs of Heinrich Friedrich Meyer in Hanover. This is certainly one of the most popular designs of the flute ever made, and many were exported from Germany to the US. At any given time there are ten or more for sale on eBay. They are often cheap, under $300, but virtually never playable. They are wooden instruments with a metal-lined headjoint and tuning barrel that almost always cracks. The pads also usually need to be replaced as well as corks and occasionally springs. They can almost always be fixed, but the cost is usually going to be higher than the real value of the flute.

When they are fixed up, some of these flutes actually can play well at A=440, especially ones made for the early 20th-century American market, but the quality range is great. If you look in a turn-of-the-century Sears & Roebuck catalog, you will see many of the same types of flutes you see on eBay and get an idea of their relative worth.

There are dealers, such as myself, who generally sell only flutes that have been fully restored, tested, and properly documented. Many people who sell in this manner also do their own restorations. Their prices are generally higher, but there is a much smaller risk involved with your purchase.

Maison Souchette, France, simple system 5-key

Learning More About Old Flutes

There are a small number of fine books every serious collector should own. The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, William Waterhouse is a valuable resource. It is out-of-print, but you can find a copy if you look. If you are interested in English flutes, Robert Bigio’s book Rudall, Rose & Carte: The Art of the Flute in Britain is an excellent investment. Woodwinds in Early America by Douglas Koeppe contains superb information on American flutes. Ardal Powell’s book, The Flute, provides a wonderful historical overview of the development of the instrument.

There are many museums in the US with fine collections of historical instruments, including flutes. In addition, visiting people with private collections can be the best way to experience a flute as you are much more likely to hear them played and may be able to try them yourself. Many collectors treat their instruments as an educational tool.

Facebook groups are one of the best source’s of information for flute collectors and players of original flutes. These are great places to ask questions about a flute you have or one you are considering purchasing. The two I frequent most are Flute History Channel and The 19th-Century Flute. There are many knowledgeable people on these pages including collectors, players, teachers, makers, and restorers. There are also a couple of websites that are useful, especially if you are trying to identify an instrument. Look at www.oldflutes.com and my site www.originalflutes.com.

Flute collecting is a wonderful pastime which if you are careful and patient can yield exciting things. I would urge all flutists to experience trying the various styles of historical flutes – if possible hopefully with the help of someone who does play them well. For modern flute players a little time with a conical Boehm flute can be especially interesting. These instruments were very popular well into the 20th-century although they are virtually never heard today.

Foot joints by Barfoot, London – Goulding, London – Godfroy, Paris – Palanca, Italy

* * *

Tips for Buying Flutes on eBay

Here are some suggestions for buying on eBay. Although they are not trade-secrets, many people are not aware of these things. They apply equally to most anything one would buy on an eBay auction.

1. Unless you know otherwise, do not accept an item description as being accurate. Do your homework

2. Condition is a huge factor in determining the value of a flute. Most things can be fixed but that can get expensive. A nice original case and accessories like a grease pot, screwdriver, or swab stick, will raise the value.

3. Try to determine the pitch of the flute if that matters to you.

4. Examine photographs very carefully. The sellers may not be trying to deceive you, but they sometimes list a flute as being in excellent condition” when it is really missing a key or worse. If you do not see what you need to, request more photos and be specific.

5. Remember to check the embouchure hole carefully. Embouchures were often enlarged, especially on cheap flutes. This is never a good thing.

6. If you are planning to bid, think hard about how much you really want to spend and bid that amount.

7. Best-Offer auctions can be quite good. If you are interested in an item make a reasonable offer

8. There is no reason to ever bid on an item until it only has 10 seconds or less until the auction ends. Bidding early forces the price up. Sellers want you to bid early, but as a buyer you should wait. Remember if you bid late, you will probably only have one opportunity before the auction ends, so bid the maximum you are willing to spend.

9. Don’t bid on an antique flute expecting that you can send it back if you don’t like it. A few buyers offer that option, but generally if you buy it, it is yours.

Monzani & Co, London, 1825, 8-key flute