Flutist Claire Chase is a soloist, collaborative artist, and advocate for new and experimental music. In 2001, she founded the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE). The ensemble has premiered over 800 works and has won the Trailblazer Award from the American Music Center and the Ensemble of the Year Award from Musical America Worldwide. In 2012 she was named a MacArthur Fellow and with the monetary grant has embarked on a 22-year commissioning project, called Density 2036, to create an entirely new body of repertory for solo flute.

What led you to form ICE?

What led you to form ICE?

During my junior year at Oberlin, I received a $5,000 grant from the Theodore Presser Foundation and decided to assemble a contemporary music ensemble of 15 people, commission five new pieces in the celebration of the year 2000, produce a concert and recording, and get 750 people in the audience. As I was putting together the grant application, my advisors said that it was too much. I tried to separate out the different components, but I could not do it. I did not think that any of those things were separate, and I could not imagine the project without doing all of it. I spent a year producing the concert. I put it all together and learned everything by just doing it.

In the process I realized that this was what I wanted to do with my life. I did not have a name for it, and there certainly was not a defined career path, but it became very clear to me that this was what I was called to do. It combined all of the things that I love. I like jumping off the proverbial cliff of commissioning, nurturing and bringing into being a world premiere. I enjoy connecting people to the essential ritualistic act of giving a concert, talking to kids about music, getting them to concerts of contemporary music, and sharing a nascent body of repertory with other ensembles, musicians, and composers.

After graduation I planned to move to Chicago to wait tables, gig, teach, and have a little time to figure out what was next. Michel Debost wanted me to take auditions, but I did not feel ready for that or that it was what I was meant to do. Halfway through the bus ride to Chicago, I realized that I had already started doing the work that I wanted to do and with the people that I wanted to do it with. I got off the bus and checked out a book from the Chicago Public Library on how to start a non-profit organization. Six months later, we gave our first concert on January 6, 2002. Our budget was $603, which was my holiday catering tips. I got food and wine donated and a guy at Kinko’s copied our flyers for free. The 15 musicians came from all over the country, and we presented our concert. After that I put together a board of directors and had our first real fundraising campaign. It grew very fast with the budget doubling between years one and two and two and three. This growth continues today.

What is the Density 2036 project?

The project is a 22-year commissioning initiative based on the transformative power of Edgard Varèse’s Density 21.5. The pieces do not have to directly reference Density 21.5. Instead it is meant to be a poetic and conceptual jumping-off point for composers to think about what the flute is in the 21st century, what its language is, who the audience is, what stories it tells, and so forth. What interests me tremendously is the potential for the intersection of many different disciplines and ways of thinking about performance practices and the development of instruments. People often ask whether it will be boring to do the same project for 22 years. In many ways I believe it is freeing because it combines all of these things that I was doing in different disciplines with different projects and has created a funnel for them to be harnessed into one initiative.

Is there a commissioning plan?

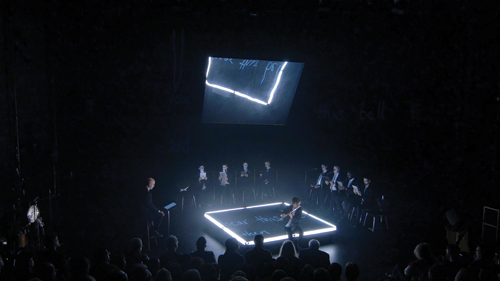

Every year, new pieces are commissioned and premiered at The Kitchen, a venue in Manhattan. The first three years explored how far we could amplify, expand, and stretch the concert recital format to make it a new kind of performance experience, while preserving some of the traditions of a programmed concert, and with the inclusion of many different styles and composers. For example, the pieces were played without pause in between, sometimes slightly overlapping, from the beginning to the end of the concert. In addition, staging, lighting, choreography, and stage design added to the experience of each piece. Last year there were five new pieces, this year there are six. The concept for this year is based on duos: glissando flute and ondes martenot (Suzanne Farrin), flute with eight voices (Richard Beaudoin, Roomful of Teeth), and contrabass flute with jazz drum set (Tyshawn Sorey). Next year, I am working with a single composer, director, and designer to create a 90-minute opera for solo flute and mass community participation. We are looking to create a body of work for three years that explores the idea of the flute and flutist as the centerpiece of a one-woman show, with a single composer as the collaborator.

Tell us about your early studies.

When I was three, my parents took me to hear the San Diego Symphony play Brahms Symphony No. 4. I saw this instrument in the middle of the orchestra and even before I heard its sound, the way that it looked and the way that it shone blew my mind. It was the only thing I wanted to look at and listen to. After the concert, I told my mom, that it was the one that I wanted to play. Of course, it was way too early to start the flute, so I took piano, violin, and voice lessons first. Finally, on my eighth birthday, I got a flute. I didn’t want to put it down; all I wanted to do was practice. I started studying with John Fonville in San Diego when I was ten. He played a lot of contemporary music and is a phenomenal composer and improviser. When I was twelve, he played Density 21.5 for me. It was a transformative moment. Four and a half minutes of the most powerful flute playing and the most powerful piece I had ever heard. That is what really got me bitten by the bug to explore new sounds.

What did you study with Michel Debost?

I met Michel Debost at the Oberlin Summer Flute Academy and just loved him. He is that rare bird who is as gifted as a teacher as he is as a performer. There are so few people who have that combination of gifts. The Michel Debost school of flute playing is the same for everybody. Everyone plays the same etudes and the same repertoire. There is a repertoire list each year, and everybody gets through all of it, depending on your grade level. This might seem confining, but I actually found it very liberating because you have a schedule to work up against. It is so good to have structure.

Debost was equal parts philosopher and poet as a teacher, and he was tough. We definitely had our conflicts. I wanted to play contemporary music and he was supportive of that, but of course I had to play all of the classics as well, which I also loved. Towards my third and fourth year, he let me go and do some of my own things. He set the bar extremely high.

The foundation that he gave me is so strong. I still do the Scale Game every day. He has it structured so your mind and body are always engaged and you cannot go on autopilot. I like to switch up my routine depending on how much time I have. Over the past few years, I have been performing so much and my practice time is so limited that what I choose to do in the warm up and how I vary it every two or three weeks is really critical. Michel gave me these tools.

He told me one day, “Ma petite Claire, you have two professors.” He pulled my left ear, “one professor,” then pulled my right ear, “two professor. Those are the only professors you have. Use them!” He also had a voracious appetite for literature, art, cinema, and such an appreciation of beauty and curiosities beyond music which were so inspiring to me. Some of my favorite lessons were those where we did not play the flute at all. We went to look at art at the Oberlin art museum, and then we would walk in the park and talk about life. All of that stuff shows up in your playing.

Why did you pursue a career in contemporary music instead of classical music?

When you love something, it decides for you where you are going to spend your energy. When we love a piece of music, it is really difficult to think about anything else. The process of creating new music just took hold of me. I wasn’t making decisions; I was just following this thing that I loved, and was deeply passionate about figuring out how to share. I definitely questioned my decision and know that my mentors, teachers, and family questioned what I was doing. There were a few moments where I almost decided I was going to go back to graduate school, but I never actually put in an application. I would always be drawn back. There is a Rumi poem that says, “Let yourself be silently drawn by the stronger pull of what you really love.” In every moment that I listened to that little voice that said I should go to graduate school, take auditions, or play Mozart concertos rather than commission new concertos, I would indulge it for a while and then I would just be silently drawn back to the stronger pull of what I really wanted to do.

What about classical music?

I play and listen to Bach every day. My life is so crazy and unpredictable that I appreciate having certain rituals like this. I do not want to play Mozart flute concertos with an orchestra because there are so many fantastic flute players who do it beautifully and phenomenally so much better than I can. I love listening to them. I treasure recordings by artists like Emmanuel Pahud, Michel Debost, and Marina Piccinini, but I don’t know that the world needs me to go out and do that.

While I do listen to a great deal of classical music, I am always exploring, discovering, and researching contemporary music. I do not really like to use the word contemporary music anymore and use classical less and less unless I can define what that means. My idea of classical music is not just Bach to Beethoven but instead dates back to 600 B.C. with the first evidence of notated music. It continues through today and includes non-western traditions. Why is classical Indian music not classical music or an artist like Prince? It is all connected, so I do not espouse the delineation of these things. I feel this is a really important idea and one of the most exciting things about the time that we are in is that we can belong to so many different musical communities. We do not have to attach ourselves to one thing and just continue repeating it. Music is constantly changing and evolving, and we get to come along for the ride.

What do you say to people who do not like contemporary music?

I like to talk to people about what puts them off. For example, why do they think it is weird? I do not know why it is any weirder than things that people say, or why the sounds we hear in the city every day are stranger than the sounds that we make on a percussion instrument or the flute. I like to talk about why people define things so narrowly. The point of being alive is to change and learn, and I believe that artists and teachers should do that with great conviction. I believe this is true whether you love early music, romantic music, or music that is written today. As an artist, I try to do what inspires me and go towards those places that are actually the most uncomfortable and find out what secrets are lodged there. I enjoy inviting audiences to think that way not just about listening to music but about their lives and listening to other people. Mahler said this so well: “Tradition is not the worship of ashes, but the preservation of the fire.” That one statement just puts to rest any notion that there is a difference between classical and contemporary music.

What advice would you have for musicians who are still in school or at the beginning of their careers?

Think about what moves you and what you love. Then ask yourself, how do I share this? With time as you grow, there will be different answers. In two years, the answers should be different from what they are today. I think that students are taught in classical music training that they should have one idea of what they are doing, and they have to just go toward that idea. They become focused on just that repertoire and vision of themselves. I think it is much harder than that. That is, who are you today? How can you most honestly express that through music and take responsibility for how you share it? As Oscar Wilde said: “Be yourself, everyone else is taken.”

* * *

International Contemporary Ensemble

ICE is a 35 member new-music ensemble dedicated to transforming the way music is created and experienced. The group currently serves as artists-in-residence at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts’ Mostly Mozart Festival, and previously led a five-year residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. New initiatives include OpenICE, which offers free concerts and related programming wherever ICE performs, and enables a working process with composers to unfold in public settings. EntICE, a side-by-side youth program, places ICE musicians within youth orchestras as they premiere new commissioned works together. After 15 years as the executive director of ICE, Claire Chase stepped down this fall to pursue her ongoing personal projects, and passed her leadership role to other members of the group.

Claire Chase, a native of Leucadia, California, is a graduate of the Oberlin Conservatory of Music where she studied with Michel Debost. She also studied with John Fonville and Damian Bursill-Hall. She was the 2009 Grand Prize Winner of the Concert Artists Guild International Competition and in 2015 was honored with the American Composers Forum Champion of New Music Award. For more on the Density 2036 project go to clairechase.net.